“The World’s Fastest Indian” is a movie about an old coot and his motorcycle, yes, but it is also about a kind of heroism that has gone out of style. Burt Munro is a codger in his 60s who lives in Invercargill, New Zealand, takes nitro pills for his heart condition, and has spent years tinkering with a 1920 Indian motorcycle. His neighbors wish he would take a break once in a while to mow the grass.

By 1967, Burt thinks the Indian may be about ready to travel to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah and take part in the annual Speed Week. This project involves fund-raising in Invercargill, and a long journey that takes him overland in America, where he meets among others an accommodating widow who takes him to visit her husband’s grave. In Bonneville, where millionaire drivers are sponsored by big corporations, no one has ever seen anyone like Burt or anything like his ancient machine.

He should have registered weeks ago, but the officials lack the heart to turn him away. They are amazed when they inspect his machine. No braking chute? No brakes? “Where’s your fire suit?” Can that be a cork on his gas tank? There is no tread on his tires. Is that mechanical part a — kitchen hinge?

Why do they allow this man to risk his life in defiance of every safety standard at Bonneville? I think it is because Burt loves his motorcycle, and cannot believe she would harm him; the steadfastness of his trust seduces them. When Burt discusses his motorcycle, which he rhymes with Popsicle, he gets into theories he must have pondered long into the night in his garage in New Zealand: “The center of pressure is behind the center of gravity,” he explains, as if that explained anything. Or maybe it does. With Burt, you can never be sure.

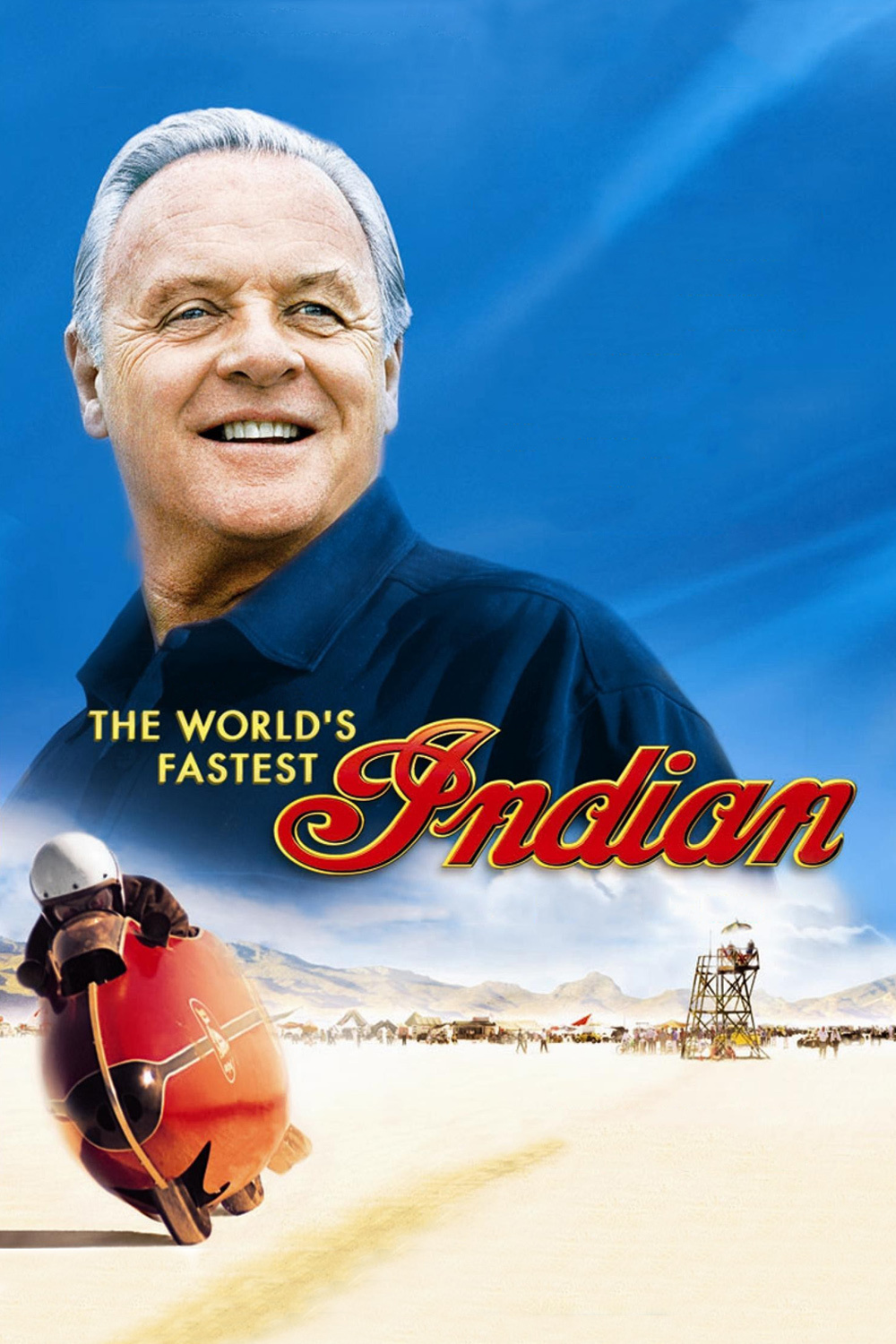

This is one of Anthony Hopkins’ most endearing, least showy performances. The man who created Hannibal Lecter and Richard Nixon is concerned here with the precise behavior of a quiet, introverted man who is simultaneously obsessed and a little muddled. It’s as if his fellow racing drivers have been visited by a traveler from the dawn of their sport, when guys tinkered with their machines in the tool shed and roared up and down country roads. Burt Munro is a man for whom the world seems brand-new: He is amazed to enter a restaurant and see, for the first time in his life, a menu with photographs.

Bonneville involves not racing but time trials. Burt has customized his Indian into a low, streamlined machine which he rides while flat on his stomach. He has a pair of goggles and a battered helmet that looks like Lindy once wore it, and he roars off into the desert sun like a crazy kid. Bonneville has never seen anyone like him.

Burt Munro was a real man, and the film is based on fact. Roger Donaldson, the movie’s writer and director, grew up in New Zealand, where Munro was a folk hero. He wrote the first draft of this script in 1979, after a 1971 documentary, and then life took him to Hollywood and to big-budget thrillers like “No Way Out,” and now at last he has returned to tell the story of a hero of his youth.

It is also the story of certain New Zealand characteristics, among which is self-effacing modesty. Burt Munro would think it unseemly to call attention to himself, although he is happy for his Indian to get attention. (Before one race, he pops a nitro pill into the gas tank and as he swallows the second, he explains, “one for myself and one for the old girl.”) In an era of showboat sports superstars, how strange to see old Burt challenge one of the most durable records in racing and then actually be embarrassed by the attention.

Read no further if you do not want to know how Burt does at Bonneville, although perhaps you have already guessed that “The World’s Fastest Indian” is not about the second-fastest Indian. Yes, in 1967 Burt coaxed the Indian to 201.85 mph, even as a muffler was burning the flesh on his leg. That set a record in the category of “streamlined motorcycles under 1000 cc.” It is a record, the film assures us, that still stands to this day. Burt returned nine times to Bonneville, becoming a hero, although deflecting attention with his diffidence, his shyness, his way of talking about the Indian instead of about himself. We are reminded that when Lindbergh flew the Spirit of St. Louis across the Atlantic, he titled his autobiography We — so that it also included his airplane. That’s how Burt feels about the old girl.