The child is the father of the man. –Wordsworth

Renee LeBlanc was a beautiful little girl; she was a professional model before she was 12. Then Renee was injured in a fall from the family garage and descended into depression. Her parents agreed to shock therapy; in two years she had more than 200 treatments, which her son blames for her mental illness, and for the pain that coiled through his family.

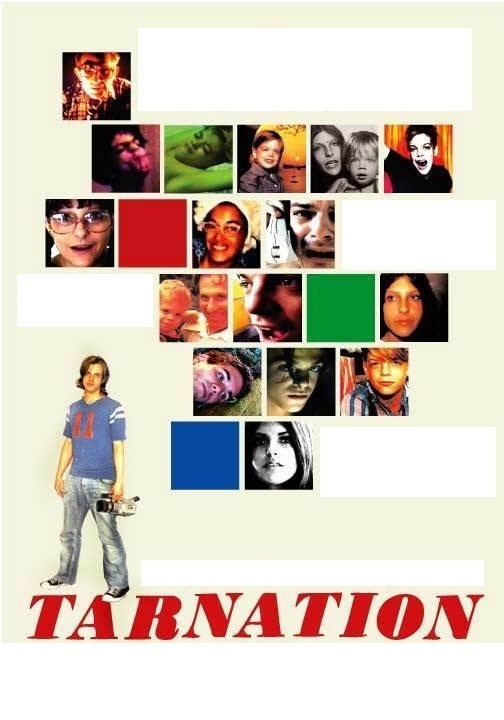

“Tarnation” is the record of that pain, and a journal about the way her son, Jonathan Caouette, dealt with it — first as a kid, now as the director of this film, made in his early 30s. It is a remarkable film, immediate, urgent, angry, poetic and stubbornly hopeful. It has been constructed from the materials of a lifetime: Old home movies, answering machine tapes, letters and telegrams, photographs, clippings, new video footage, recent interviews and printed titles that summarize and explain Jonathan’s life. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” T.S. Eliot wrote in “The Waste Land,” and Caouette does the same thing.

His film tells the story of a boy growing up gay in Houston and trying to deal with a schizophrenic mother. He had a horrible childhood. By the time he was 6, his father had left the scene, he had been abused in foster homes, and he traveled with his mother to Chicago, where he witnessed her being raped. Eventually they both lived in Houston with her parents, Adolph and Rosemary Davis, who had problems of their own.

Caouette dealt with these experiences by stepping outside himself and playing roles. He got a video camera and began to dress up and film himself playing characters whose problems were not unlike his own. In a sense, that’s when he began making “Tarnation”; we see him at 11, dressed as a woman, performing an extraordinary monologue of madness and obsession.

He was lucky to survive adolescence. Drugs came into his life, he tried suicide, he fled from home. His homosexuality seems to have been a help, not a hindrance; new gay friends provided a community that accepted this troubled teenager. He was diagnosed with “depersonalization disorder,” characterized by a tendency to see himself from the outside, like another person. This may have been more of a strategy than a disorder, giving him a way to objectify his experiences and shape them into a story that made sense.

In “Tarnation” he refers to himself in the third person. The many printed titles that summarize the story are also a distancing device; if he had spoken the narration, it would have felt first-person and personal, but the written titles stand back from his life and observe it.

The “Up” series of documentaries began with several children at the age of 7. It revisits them every seven years (most recently, in “42 Up“). The series makes it clear is that the child is indeed the father of the man; every one of its subjects is already, at 7, a version of the adult they would become. “Tarnation” is like Caouette’s version of that process, in which the young boy, play-acting, dressing up, dramatizing the trauma in his life, is able to deal with it. Eventually, in New York, he finds a stable relationship with David Sanin Paz, and they provide a home for Renee, whose troubles are still not over.

The method of the film is crucial to its success. “Tarnation” is famous for having been made for $218 on a Macintosh and edited with the free iMovie software that came with the computer. Of course hundreds of thousands were later spent to clear music rights, improve the soundtrack and make a theatrical print (which was invited to play at Cannes). Caouette’s use of iMovie is virtuoso, with overlapping wipes, dissolves, saturation, split screens, multiple panes, graphics, and complex montages. There is a danger with such programs that filmmakers will use every bell and whistle just because it is available, but “Tarnation” uses its jagged style without abusing it.

Caouette’s technique would be irrelevant if his film did not deliver so directly on an emotional level. We get an immediate, visceral sense of the unhappiness of Renee and young Jonathan. We see the beautiful young girl fade into a tortured adult. We see Jonathan not only raising himself, but essentially inventing himself. I asked him once if he had decided he didn’t like the character life had assigned for him to play, and simply created a different character, and became that character. “I think that’s about what happened,” he said.

Looking at “Tarnation,” I wonder if the movie represents a new kind of documentary that is coming into being. Although home movies have been used in docs for decades, they were almost always, by definition, brief and inane. The advent of the video camera has meant that lives are recorded in greater length and depth than ever before; a film like “Capturing The Friedmans” (2003), with its harrowing portrait of sexual abuse and its behind-the-scenes footage of a family discussing its legal options, would have been impossible before the introduction of consumer video cameras. Jonathan Caouette not only experienced his life, but recorded his experience, and his footage of himself as a child says what he needs to say more eloquently than any actor could portray it or any writer could describe it.

The film leaves some mysteries. Caouette visits his grandfather and asks hard questions but gets elusive answers; we sense that the truth is lost in the murkiness of memory and denial. The 200 shock treatments destroyed his mother’s personality, Caouette believes, and they could have destroyed him by proxy, but in “Tarnation” we see him survive.

His is a life in which style literally prevailed over substance; he defeated the realities that would have destroyed him by becoming someone they could not destroy.