No one starts with a clean slate in adulthood. How you deal with this reality says a lot about who you are: how do you make sense of the narrative of your life, how do you fit your own past into your present story? This is the central tension of Claire Denis’ emotionally volatile and unpredictable “Both Sides of the Blade,” with Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon giving two tremendous performances as a contented couple whose lives are exploded by a chance encounter in the street, by the past strolling back into the present, re-asserting its primacy with no warning. The past is the ultimate party-crasher.

This is Denis’ third collaboration with Binoche (“Let the Sunshine In” and “High Life“), and here she has teamed up again with Christine Angot (who co-wrote “Let the Sunshine In”) to craft a script out of Angot’s 2018 novel Un Tournant de la vie. Angot’s novel is mostly dialogue, which is reflected in the “talky” screenplay, where the language is finely wrought and intricately observed, spiked with indirection, avoidance, and blatant lying (to each other, and to themselves). When the truth comes out, it bursts forth messily after being trapped so long in a container. “Both Sides of the Blade” has had multiple titles in its production history (it is still listed as “Fire” on IMDb), but the final version came from a song by Tindersticks (who did the moody score). The original French title has a certain blunt panache: “Avec Amour et Acharnement”: “With Love and Relentlessness,” but when Denis heard “Both Sides of the Blade” during the editing process, she thought it most appropriate for this story of passion’s sharpness and danger.

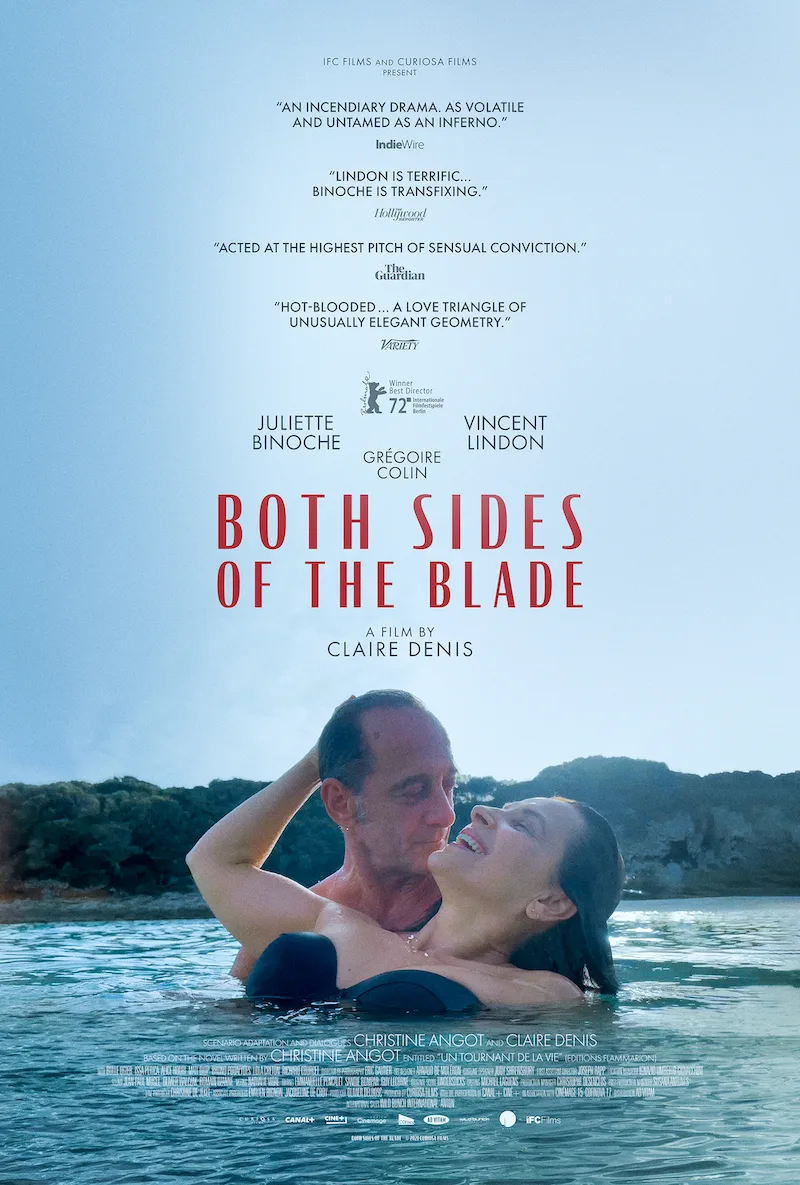

Seen in the opening sequences, floating together in a blue ocean, Sara (Juliette Binoche) and Jean (Vincent Lindon) are not just a happy couple. They are a blissfully contented and satiated couple. Too good to be true? Denis does not undercut the bliss with foreshadowing. She presents it straight. She presents everything straight. There is no exposition, since human beings don’t go around providing exposition to people who already know the story. We have to piece together what happened.

Sara is the host of a radio show, where she interviews serious people about serious subjects, war, racism, global politics. Jean is out of work, finding it difficult to get past the barriers in place due to his criminal history and past prison term (for a crime never disclosed). He makes the rounds of employment agencies, while fielding constant phone calls from his mother (Bulle Ogier). Jean’s son from a previous marriage, Marcus (Issa Perica), lives with his grandmother and things are not going well. The day after Sara and Jean come back from vacation, she gets a glimpse of a man on the street, and she stops dead in her tracks, stricken. He is François (Grégoire Colin), an old friend of both Sara’s and Jean’s, and Sara’s former flame.

Sara is completely undone by this one glance. It opens up an abyss in her life, an abyss that didn’t seem to exist only a day before. Who François is—and what happened between them—is revealed in a riveting conversation between Sara and Jean, when she tells him she saw François on the street. She’s overtly casual about it, but Jean is immediately alert to the crackling undercurrent. From then on, nothing is the same.

This is the stuff of Sirk-ian melodrama, where “the problems of three little people” definitely amount to “a hill of beans.” “Both Sides of the Blade” is a romance, a love triangle, a marriage drama, an infidelity narrative, all familiar ground, but Denis’ approach is her own. The characters exist in airtight bell jars—together, and then separately—making connection nearly impossible. The film is inside that bell jar, often breathlessly claustrophobic in its focus. Denis, and her cinematographer Éric Gautier, don’t give us a break from these people. The camera is right up in the faces of Binoche and Lindon, drinking in every pause, every tiny shift of mood or feeling, the camera almost an intrusion, a Grand Inquisitor.

When Jean and François team up in a business venture, Sara cracks apart, and Jean, in turn, cracks with her. Their behavior is often incomprehensible, but love is not known for encouraging sanity. There are moments when “Both Sides of the Blade” feels like a ghost story, where Sara’s love affair with François is the ghost haunting the current couple, but there are other times when it feels like a drug narrative. The look on Sara’s face when she sees François is not the look of a woman yearning for a past boyfriend. It’s the look of an addict, white-knuckling her way through sobriety, gazing at the drug she still misses. The conversations between Sara and Jean, as they hash out this situation (or fail to), are the meat and potatoes of this tale. Their scenes together are heart-breaking, honest, sometimes scary.

On Sara and Jean’s periphery, are smaller characters: the grandmother, baffled at her son’s absence, and completely at her wits’ end having to deal with a bored lackluster teenager (who is, understandably, pissed at being abandoned by both of his parents). Regular Denis collaborator, and now director herself, Mati Diop, has a small role as an empathetic family friend, who sees what is happening with the mixed-race Marcus, the subtleties of which his immediate family miss (or don’t want to perceive, if judging by some of Jean’s comments).

Denis is sensitive to environment and atmosphere. Consider Sara and Jean’s apartment. We really only see the bedroom, where Sara spends so much time lying in bed, her back to the camera. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of space. The balcony, looking out on the city rooftops, is a huge presence: It’s a No-Man’s-Land, a neutral space, where the warring couple can come back together. But it’s also a place of escape and secrets. Consider, too, Jean’s driving. He spends so much time driving back and forth between his apartment and his mother’s, outside of the city. He does his grocery shopping out near his mother’s house. But he never stays to visit, and avoids his son. This “quirk” is never mentioned outright but it’s fascinating. Why drive over an hour to go grocery-shopping, right down the street from your mother’s house, and not stop by to say hello? Maybe being behind the wheel gives Jean a sense of control he lacks everywhere else.

Lindon gave one of my favorite performances of 2021 in “Titane,” as the steroid-pumped tender-souled fire chief with the big tragic eyes, and he is superb here as well. There’s something broken in Jean, and perhaps he didn’t realize just how bad it was until Sara says, too casually, “I saw François today.” He is also drawn to his old friend, a sketchy guy who represents an entryway into the criminal underworld again. When Jean accuses Sara of being in François’ “grip,” she could say the same thing to him. And Binoche is all raw nerves. It’s a destabilizing kind of performance, because she lies, to herself and to Jean, so much so that when she speaks the truth it sounds like a lie. She is so placid and competent in the opening scenes, and the mask falls away so completely when she sees François that you wonder how she managed to carry on with this new relationship at all, let alone for a decade.

There’s an urgency in all of these confrontations and contradictions. Every moment is life or death. It’s exhausting, but again: Love is not known for being sedate. Sara has intricate conversations with heavy-hitting intellectuals on her radio show, but falls apart when trying to be forthright with her intimate partner. Jean is loving and kind to Sara, but avoids his struggling son. Sara loves Jean, but can also say with a straight face that he is “controlling” her, even though we have seen little to no evidence of that. Perception is all. If she feels it, she feels it. The truth is different depending on where you stand, and in a bell jar there’s not enough room for everyone. No matter which way you try to make a move, you bump into someone else.

Love is patient and kind, or so they say. “Both Sides of the Blade” knows that love is actually a wrecking ball.

Now playing in select theaters.