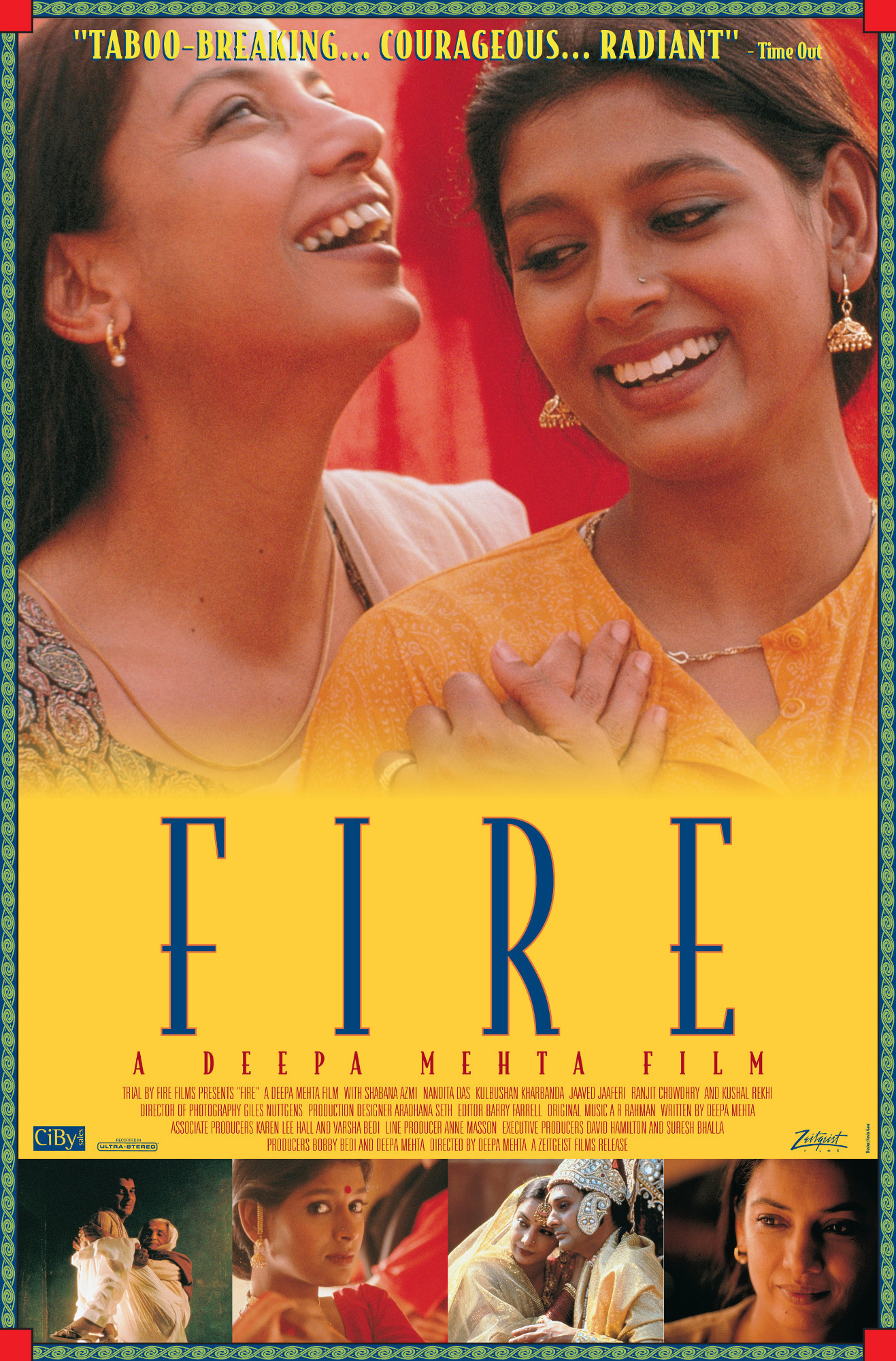

Deepa Mehta’s “Fire” arrives advertised as the first Indian film about lesbianism. Among other recent Indian productions (according to the Hindu, the national newspaper) are films about tranvestism, eunuchs, sadomasochism and male homosexuality. Along with Mira Nair’s “Kama Sutra: A Tale of Love” released earlier this year, “Fire” seems to be part of a new freedom in films from the subcontinent.

Both of these films, directed by women, resent a social system in which many women have no rights. Neither is an angry polemic; the directors cloak their anger in melodrama, in romance, in beautiful photography, and in the sort of gentle sexuality that is often more erotic than explicit, if only because it allows us to watch the story without becoming distracted by the documentary details.

“Fire” is about a beautiful young woman named Sita (Nandita Das), who marries into a New Dehli family that runs a sundries and video store. The entire family lives above the store: Her husband Jatin (Jaaved Jaaferi), her brother-in-law Ashok (Kulbushan Kharbanda), his wife Radha (Shabana Azmi), the ancient matriarch Biji (Kushal Rekhi) and Mundu (Ranjit Chowdhry), the servant who watches over the old woman during the day. Mundu’s favorite pastime is masturbating enthusiastically to videos he sneaks upstairs from the store; a stroke has rendered Biji speechless, but she has a little bell that she rings furiously at him.

It is an arranged marriage between Sita and Jatin, insisted on by Ashok because the family needs children and his wife can give him none. (“Sorry, no eggs in ovary,” the doctor explains.) Jatin, a modern young man with few serious beliefs, religious or otherwise, has gone along with the marriage but flaunts his mistress Julie (Alice Poon), a Chinese woman. When Sita discovers Julie’s photo in her husband’s wallet, he is less than apologetic: “Julie is so smart, so special, so pretty–you should meet her!” It is only a matter of time until the two wives, Sita and Radha, are sharing their unhappiness while looking out over the city from a rooftop veranda. Radha is alienated from her husband–who, depressed by her sterility, follows the teachings of a swami who advises chastity. Sita is devastated that her husband does not love her. One day, simply and directly, she kisses the older woman, and the next day the older woman dresses her hair, and soon they are in each other’s arms, I think, although the sex scenes are shot in shadows so deep that censors will be more baffled than offended.

It is of course the Indian context that gives this innocent story its resonance. Lesbianism is so outside the experience of these Hindus, we learn, that their language even lacks a word for it. The men are not so much threatened as confused. Sita and Radha see more clearly: Their lives have been made empty, pointless and frustrating by husbands who see them as breeding stock or unpaid employees.

The film has a seductive resonance. Women do a better job of creating art about sex, I think, because they view it in terms of personalities and situations, while men are distracted by techniques and results. The two women are very beautiful, gentle and sad together, and the movie is all but stolen by Chowdhry, as the servant who lurks constantly in the background providing, with his very body language, a comic running commentary.