“Blank City” seems almost to argue that poverty is of great assistance to artists. Caeine Danhier’s documentary revisits an era–actually, more of a moment–when the bankruptcy of New York City coincided with a no-budget flowering of film and music on the Lower East Side, which by then had already been giving birth or shelter to artists for most of a century.

In “Alphabet City,” below 14th Street, rents were low and sometimes optional. The streets were dangerous, but artists could live there on little income. They could buy cheap Super 8 cameras, some of them stolen. They could sometimes scrounge editing facilities for as little as $10. Their screenings and the performances of their bands could take place in spaces that were cheap, free, or appropriated.

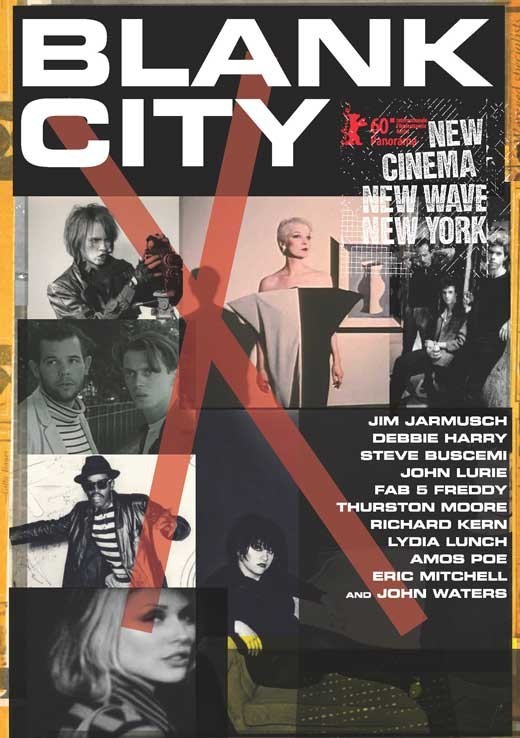

Some of those who began there are well known today: Steve Buscemi, Jim Jarmusch, Susan Seidelman, John Lurie, Deborah Harry, Jean-Michel Basquiat. Others were only briefly effervescent. A fierce democracy ruled, in which qualify was secondary and simply doing it was the whole point. Willpower was more important than skill. Lurie, remembering the time, muses that talent was beside the point: Film people started bands, musicians made films, and there was a time when he feared to reveal he could actually play the saxophone because it might count against him. In London at about the same time, Punk Rock stars like Sid Vicious couldn’t play the guitar and it was an open question whether he could sing.

The documentary does a formidable job of sampling countless films now mostly forgotten (and a few, like Seidelman’s “Smithereens” and Jarmusch’s “Stranger Than Paradise,” that stood the test of time). It gathers many of the artists, now middle-aged, to recollect a time of heedless youth.

Andy Warhol had already made his statement about 15 minutes of fame. Here is a group of artists who were sometimes more focused on five minutes of notoriety. If some like Jarmusch and Buscemi became considerable artists, that is more a tribute to their abilities than to their period. Variously described as No Wave, the Blank Generation or the Cinema of Transgression, their art was more an expression of their existence than a larger statement. It was incestuous, not outgoing.

Curiously, although some of them deserve to, none of the artists make any claims for the work, or express much admiration or enthusiasm for it. The documentary approaches it in the spirit of Samuel Johnson, who once compared a woman’s preaching to a dog standing on his hind legs: “It is not done well, but one is surprised to find it done at all.”

Many of the filmmakers here were inspired by the earlier example of John Cassavetes. If one assembled Cassavetes and his company (Gena Rowlands, Ben Gazzara, Peter Falk, Seymour Cassel), you would hear them talking about their ambition to make good and even great films. No one is that bold in “Blank City.” I saw a number of these films at the time, liked a few. This doc is interesting and worthy, but it is unlikely to send you seeking most of the films sampled in it. That was then, this is now, and it was fun while it lasted.

Now playing at Facets Cinematheque.