“Black Mass,” about the tangled criminal history of Boston gang boss James “Whitey” Bulger, is a bizarre movie. It really doesn’t work until you tune into its wavelength. But if can do that, you may start to see method behind the film’s madness and end up feeling as I did—that for all of its flaws, it’s the first film since “Eastern Promises” that has added anything truly fresh to the old school street-level gangster story.

The general outlines wouldn’t seem to promise anything like that sort of experience, and Jez Butterworth and Mark Mallouk’s screenplay sometimes treats its flashback structure (articulated through FBI interrogations of key Bulger associates) as an excuse to tell, even summarize, rather than show. Testimonials become voice-over narration that papers over holes in the chronology. We meet Bulger and two powerful people who shield and enable him: his senator brother William “Billy” Bulger (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his childhood friend turned FBI agent James Connolly (Joel Edgerton). We watch as Connolly hatches a plan to pay back Bulger, who protected him when they were kids, by helping the gangster inform on the Italian mob that’s muscling in on his turf—essentially offering up the FBI as Bulger’s unwitting private army, waging war on rivals. We meet Bulger’s doting girlfriend Lindsey Cyr (Dakota Johnson) and his adorable son, Douglas Cyr (Luke Ryan), and of course Bulger’s criminal gang; their ranks include Jesse Plemons, Rory Cochrane, and the great W. Earl Brown, who’s turning into the Warren Oates of modern urban potboilers. All of the performers are superb and have at least one indelible moment, but remain rather undefined as individuals. They fade in and out of the story willy-nilly, and sometimes when one of them shows up again you’re surprised to see him because you forgot he was still alive. The sole exception is Peter Sarsgaard, whose supporting turn as a jumpy cokehead sums up a man’s pathetic life in just four scenes.

There are moments where you may wonder if the film’s mostly dour tone is a mistake. Bulger’s arrangement with the FBI—enabled by his lapdog Connolly, who thwarts testimony and fudges evidence to keep his pal from getting prosecuted—seems so transparently a con that you wouldn’t believe it went on for years unless outside reading confirmed that yes, indeed, this is how it happened. The staggering incompetence this film attributes to Boston’s bureau of the FBI suggests that Cooper and company might’ve missed the boat by not turning “Black Mass” into a black comedy about how easy it is to corrupt institutions from within. (Kevin Bacon’s performance as Connolly’s incredulous superior feels more comic than dramatic; on some level he knows what kind of con is being run and can’t believe how hard it is to prove it.) Still, you get a taste of that fundamental absurdity as the film drifts along—particularly through Connolly. He’s one of the great weasels in movie history, and in some ways a more disturbing character than Bulger, because he pretends to be a good guy.

Directed by Scott Cooper (“Crazy Heart,” “Out of the Furnace“), “Black Mass” has been described as derivative work that leans too hard on savage violence, talk of loyalty and honor, profane banter and other elements familiar to fans of Martin Scorsese, whose gangster films provide much of its DNA. This is all true. But it’s also a superficial way of dismissing the film while ignoring its essence. In its heart, “Black Mass” is a moral tale with not-at-all-subtle religious overtones. It’s about how evil can flourish simply by being more charismatic and decisive than good. If you’ve ever asked yourself how, say, one bully on a subway car could berate his girlfriend for twenty stops without anyone else intervening, or how four men with box cutters could hijack a crowded airliner, this movie answers the question. It stages Bulger’s ongoing, multi-decade rampage as a waking nightmare that its participants couldn’t believe was happening even as it happened. The very idea that an agent of chaos like Bulger could exist comfortably in a major city for years—going to prison and then getting out again and picking up right where he left off, running numbers and controlling vending machines and dealing drugs and killing enemies on the streets of South Boston—seems unreal. The movie taps that unreality in bold, uncanny ways.

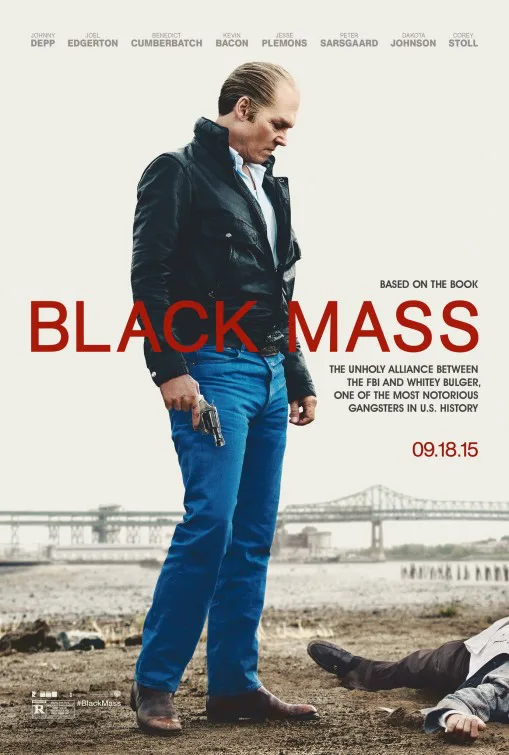

Johnny Depp plays Bulger under such heavy makeup that if you stood him next to a Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum sculpture of the same character, you wouldn’t be able to tell which was the statue. He’s the only character who is not immediately plausible as a human being. Given the way that Cooper and his cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi photograph him, this seems deliberate. With his dead eyes, ashy skin, slicked-back grey hair, dingy track suits and sagging slacks, Bulger might be a gangster ghoul. The film treats him as a literal monster, often silhouetting him or veiling him in darkness or partial shadow. One shot pictures Bulger from overhead, lying on a couch and staring unblinkingly up at the ceiling while the camera zooms out slowly: it’s the way you’d photograph Dracula chilling in his coffin. In a scene late in “Black Mass,” Bulger knocks on the bedroom door of a woman who’s reading “The Exorcist.” When Bulger stalks and shoots an informer in a parking lot, he seems to swoop out of the sun like a dragon, and when he leaves the scene of the crime, the harsh gold light halos him like Leatherface at the end of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” Touches like these make “Black Mass” feel less realistic than expressionistic—like Scorsese’s remake of “Cape Fear,” which envisioned ordinary people being terrorized by a diabolical ex-convict who seemed as unstoppable as Michael Meyers in “Halloween,” or the Terminator, or the original silent-film bloodsucker Nosferatu, who could paralyze mortals by looking into their eyes.

What we’re seeing in “Black Mass,” then, is not exactly Bulger, although we do see small-scaled moments of him interacting with his lover and son and underlings, as a regular person might. Mostly we’re seeing the idea of Bulger: what Bulger represented to the people he hoodwinked and frightened and bent to his will. The story is told mainly through the eyes of Bulger’s criminal associates. They come forward, one after the other, to describe some new facet of their boss’ awfulness and admit their inability to reject it. In a scene where Bulger strangles another potential informant, the camera moves away from the murder to study the reactions of the man who enabled it, the better to absorb his shocked realization that he still has a bit of soul left and doesn’t want Bulger to steal it.

We never gain access to Bulger’s emotional interior. We’re always looking at him from some storytelling remove. That he’s always being reacted to or described, rather than entered into and understood, contributes to the notion of Bulger as “Bulger.” Cooper shoots most of the film’s FBI interrogation room scenes, and many of the scenes where Bulger tries to pry information or extract pledges of loyalty from his men, in a simple, tightly-framed, shot-reverse shot pattern, like a priest and a parishioner in a confession booth. This, too, is appropriate. What the other characters are describing (or confessing to) is an ongoing pact that they made with a real-life devil, and the irrevocable moral, perhaps spiritual damage they realized they had suffered too late to save their souls. Tom Holkenburg’s score is funereal, music for a tragic recollection. At times it hits very low notes that seem to have been played on a pipe organ, as if making good on the film’s punny title.

All this makes Depp exactly the right person to play Bulger in “Black Mass.” In many of his other roles he seems to be channeling actors who made extravagant makeup and extreme gestures part of the experience: Lon Chaney, Peter Sellers, Orson Welles. This is another performance in that vein: a new panel to add to a gallery that showcases the likes of Edward Scissorhands, Willy Wonka and Captain Jack Sparrow. While the performance has moments of dry humor and even tenderness (mainly towards Bulger’s girlfriend and son and his sainted mother, who cheats at cards) Depp is mainly portraying the myth here, not the man; not who Bulger was, but what he meant. In that context Depp’s choices, and the film’s, seem spot-on. Depp is chilling here in the way that great horror movie actors from the 1930s and ’40s are chilling.

As sound as its central idea is, the execution of “Black Mass” is flawed. For most of its running time, it seems to be ramping up to greatness, only to turn around and sit down and brood a bit more. It’s frustratingly not-quite-there, and half-assed in some ways. But it has a vision, and it’s a powerful one. It’s a gangster horror movie. It lingers in the mind.