“Do you want…to see? You have to be wearing the watch. You light a cigarette. You push and turn right through the silk. You fold the silk over…and then…you look…through the hole.”—Lost Girl (Karolina Gruszka) in “Inland Empire”

I often describe my favorite artworks as the gifts that keep on giving, since they reveal new layers of meaning every time I view them. This is often due to their skill in bringing us closer to the realm of the unseen, as surrealist master David Lynch did in his aforementioned 2006 experimental epic, affirming just how little we know about the parallel planes of reality situated right in front of our faces. Like the Lost Girl guiding Laura Dern’s heroine down the proverbial rabbit hole, Swedish painter Hilma af Klint gave us a new method for comprehending the world that reawakened our sense of awe about its limitless complexities.

Her imagery brilliantly linked science and spirituality in a way that illuminated the mystery of existence and its inherent duality. There are echoes of Lynch in her portrayal of doppelgängers representing the light and darkness that resides in each of us, while her recurring motif of spirals extending from a single circular shape fixed in the center of her canvas expresses her theosophist faith that all religions spring from the same source. Of course af Klint never felt destined to find happiness through marriage and family life. She was too busy giving birth to the art form of abstraction.

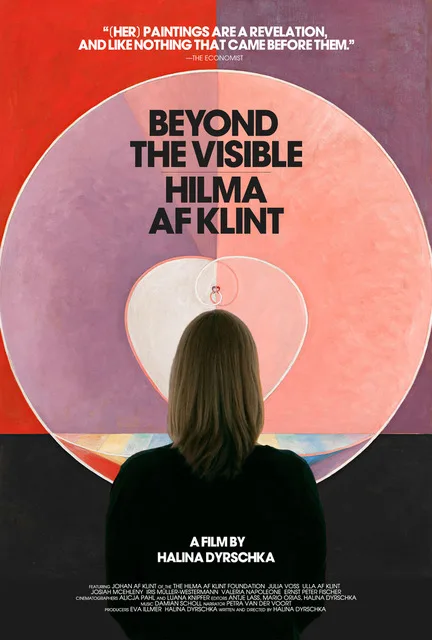

Halina Dyrschka’s debut feature, “Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint,” is one of the best films I’ve seen about fine art. It casts an entrancing spell that allows the staggering depth of its subject’s work to consume us, while showing how her trailblazing vision left an unmistakable imprint in over a century of iconic art spanning various mediums, resounding through history like a drop of colored paint in a pitcher of water. This is one of many metaphorical motifs Dyrschka poetically utilizes to convey the essence of af Klint’s artistry and the magnitude of its unsung influence.

It’s a travesty that revered institutions like the MoMA in New York City have failed to secure her worthy placement amongst the male-dominated array of celebrated painters, since her very inclusion requires the factual records of scholars to be rewritten. When one of af Klint’s philosophical mentors, Rudolf Steiner, convinced her that none of her abstract creations would be accepted by her contemporaries for another half-century, it triggered a four-year gap in her output from 1908 to 1912. Dyrschka’s film speculates that the paintings af Klint left with Steiner could’ve easily been viewed by another of his acquaintances, Wassily Kandinsky, who was determined to be recognized as the first abstract artist, though af Klint’s invention of the form in 1906 predates his strikingly similar contributions by five years.

In a jaw-dropping sequence, Dyrschka presents side-by-side comparisons of af Klint’s paintings alongside famous works from male artists that were created many years later yet inarguably rhyme with her compositions. There’s even a painting featuring four versions of the same face with different color hues that eerily resembles Andy Warhol’s portraits of Marilyn Monroe. “Beyond the Visible” instantly emerges as a worthy companion piece to Pamela B. Green’s 2018 film “Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché,” another essential historical document that also caused its team of filmmakers to take on the added role of detectives, since so much about their subject remains unknown.

Though it was long believed that af Klint’s abstract work wasn’t publicly displayed until long after her death, thus fulfilling the instructions she left for her nephew Erik, Dyrschka is blindsided by the revelation that the artist did indeed have a 1928 exhibition in the middle of London, which wasn’t known about until correspondence resurfaced 90 years later. Following af Klint’s death in 1944, Erik kept roughly 1,500 of her paintings in a storage space that wasn’t climate controlled, yet they somehow managed to survive. Among the film’s impeccable round-up of talking heads is Iris Müller-Westermann, the female curator responsible for organizing the first retrospective of af Klint’s career in 2013, the very one that first brought the extraordinary woman to Dyrschka’s attention.

I am already eagerly anticipating the inevitable biopic about af Klint, preferably starring Saoirse Ronan, who shares the painter’s clear-eyed gaze. There’s no doubt Ronan’s most recent screen character, Jo March, would’ve gotten along splendidly with af Klint, an independent outsider willing to break the rules in order to capture raw truth on her canvas. When the male models she was instructed to sketch at Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts were obligated to wear a cloth that covered their genitals, she made a point of drawing fully nude men on her own, never for prurient purposes but to ensure that no detail was left unscrutinized. The still lives of flowers and fruit that she created during her youth are stunning in their level of three-dimensional, photographic realism, and it was this sort of conventional output that earned her a living as she kept her labors of passion a secret.

Dyrschka contrasts evocative shots of nature, horizon lines, rippling water and ship masts with the texture of af Klint’s paintings to accentuate how her visual landscape may have spawned from them. Though she was a notorious vegetarian, she wasn’t above incorporating egg yolks into her painting materials. Born in 1862 to an aristocratic family of naval officers, af Klint’s understanding of sea atlases can be observed in the maps she devised, though her designs were not meant to be merely comprehended on a rational level. It was a common practice for af Klint to join her fellow members of her school’s Edelweiss Society, which included August Strindberg, to take part in séances that deepened her connection to otherworldly terrain. No wonder Olivier Assayas featured her work in his haunting 2016 exploration of clairvoyant psychology, “Personal Shopper.”

Af Klint lived such an anonymous life that her name wasn’t even displayed on her gravestone, yet she clearly deserves to be as renowned as the other creative geniuses from her country, including Strindberg and Ingmar Bergman. By inventing her own language to visualize what could not be seen with the naked eye, she built a game-changing body of work that served as the forebear to so many others, and in some ways, still feels ahead of its time. Af Klint’s mixture of blue and yellow, her respective symbols for femininity and masculinity, illustrated her conviction that “many a female costume conceals a man” and vice versa. Her belief in the oneness of all living things could be detected in her scientific analyses (linking each of us with the entire universe through our shared matter) and her spiritual preference for Theosophy (which boasted an anti-authoritarian infrastructure favoring inclusion).

Her spirit can be felt in the careers of so many giants whose work deeply impacted me during my formative years, from Lynch and Hitchcock to Malick and Henson. Each artist tapped into a universal truth that was given to them through the power of intuition, an ability af Klint beautifully articulated when describing how her pictures were “painted directly through” her, without having any knowledge of what they might depict. Dyrschka viscerally conveys the transformative power of meditation, racking focus to show what unseen wonders reveal themselves in the foreground when we adjust our gaze, while “achieving stillness in thought and feeling.” It was Einstein who admitted, “If light is simultaneously both a wave and a particle, then we no longer know what it is.” It is in that space of unknowing where timeless art flourishes.

Available via Kino Marquee today, 4/17.