The question at this point is whether “The Phantom of the Opera” is even intended to be frightening. It has become such a product of modern popular art that its original inspiration, “the loathsome gargoyle who lives in hell but dreams of heaven,” has come dangerously close to becoming an institution, like Dracula, who was also scary a long, long time ago.

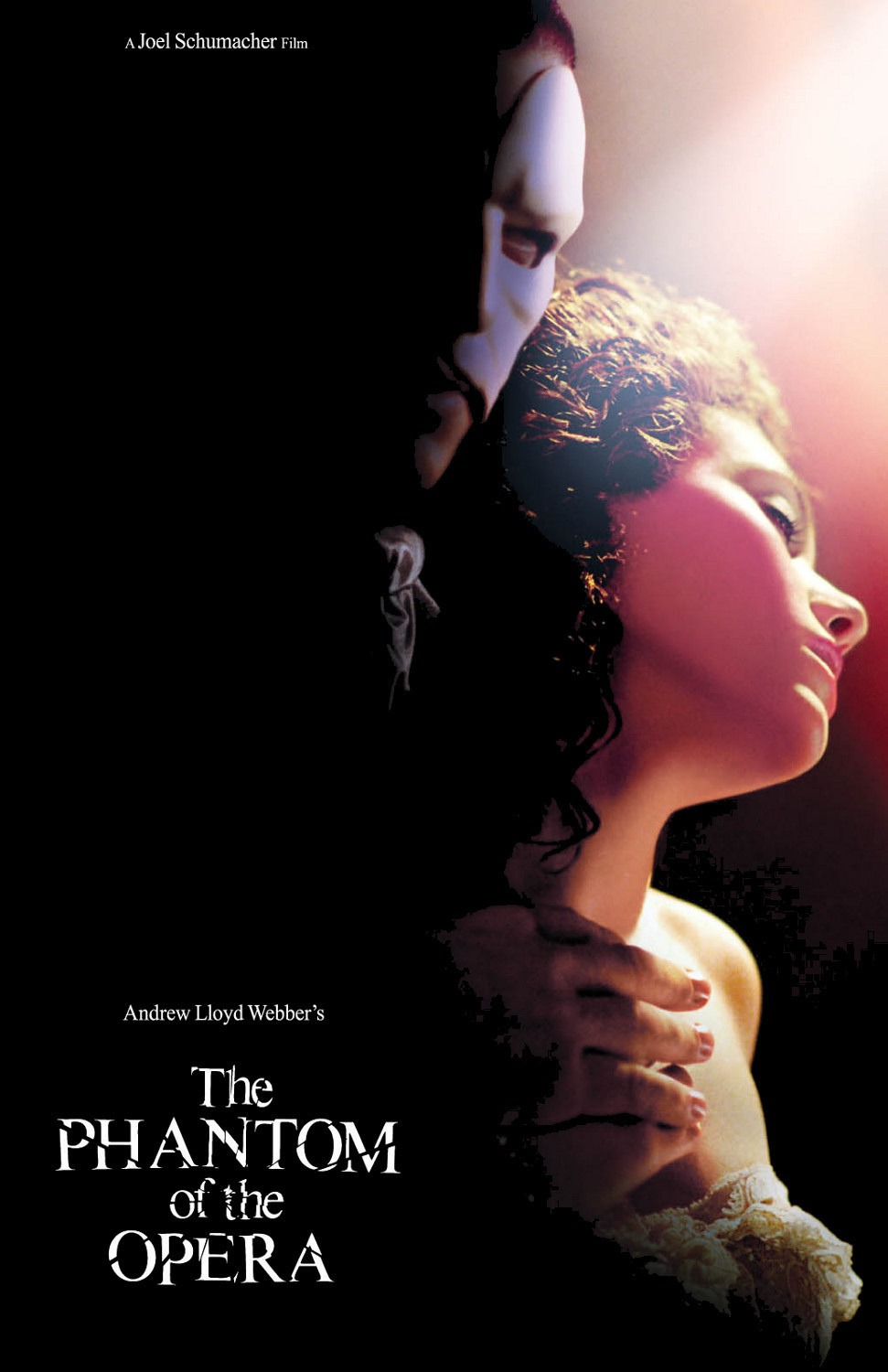

Lon Chaney’s Phantom in the 1925 silent had a hideously damaged face, his mouth a lipless rictus, his eyes off-center in gouged-out sockets. When Christine tore off his mask, she was horrified, and so was the audience. In the Lloyd Webber version, now filmed by Joel Schumacher, the mask is more like a fashion accessory, and the Phantom’s “good” profile is so chiseled and handsome that the effect is not an object of horror but a kinky babe magnet.

There was something unwholesome and pathetic about the 1925 Phantom, who scuttled like a rat in the undercellars of the Paris Opera and nourished a hopeless love for Christine. The modern Phantom is more like a perverse Batman with a really neat cave. The character of Raoul, Christine’s nominal lover, has always been a fatuous twerp, but at least in the 1925 version, Christine is attracted to the Phantom only until she removes his mask. In this version, any red-blooded woman would choose the Phantom over Raoul, even knowing what she knows now.

But what I am essentially disliking is not the film, but the underlying material. I do not think Lloyd Webber wrote a very good musical. The story is thin beer for the time it takes to tell it, and the music is maddeningly repetitious. When the chandelier comes crashing down, it’s not a shock, it’s a historical reenactment. You do remember the tunes as you leave the theater, but you don’t walk out humming them, you wonder if you’ll be able to get them out of your mind. Every time I see Lloyd Webber’s “Phantom,” the bit about the “darkness of the music of the night” bounces between my ears, as if, like Howard Hughes, I am condemned to repeat the words until I go mad. (I have the same difficulty with “Waltzing Matilda.”) Lyrics like:

Let your mind start a journey through a strange new world/Leave all thoughts of the world you knew before/Let your soul take you where you long to be/Only then can you belong to me.

Wouldn’t get past Simon Cowell, let alone Rodgers & Hammerstein.

Yet Schumacher has bravely taken aboard this dreck and made of it a movie I am pleased to have seen. To have seen, that is, as opposed to have heard. I concede that Emmy Rossum, who is only 18 and sings her own songs and carries the show, is a phenomenal talent, and I wish her all the best — starting with better material. What an Eliza Dolittle she might make. But the songs are dirges or show-lounge retreads; the dialogue laboriously makes its archaic points, and meanwhile, the movie looks simply sensational. Schumacher knows more about making a movie than the material deserves, and he simply goes off on his own, bringing greatness to his department and leaving the material to fend for itself.

I recently attended a rehearsal of the Lyric Opera’s new production of “A Wedding,” and talked with its co-writer and director, Robert Altman. “I don’t know $#!+ about the music,” he told me. “I don’t even know if they’re singing on key. That’s not my job. I focus on how it moves, how it looks, and how it plays.” One wonders if Schumacher felt the same way — not that it would be polite to ask him.

He has a sure sense for the macabre, going back to his 1987 teenage vampire movie “The Lost Boys” and certainly including his “Flatliners” (1990), about the medical students who induce technical death. His “Batman Forever” was the best of the Batman movies, not least because of its sets. Here, working with production designer Anthony Pratt (“Excalibur“), art director John Fenner (“Raiders of the Lost Ark“), set decorator Celia Bobak (Branagh’s “Henry V” and “Hamlet”) and costume designer Alexandra Byrne (“Elizabeth“), he creates a film so visually resonant you want to float in it.

I love the look of the film. I admire the cellars and dungeons and the Styx-like sewer with its funereal gondola, and the sensational masked ball, and I was impressed by the rooftop scenes, with Paris as a backdrop in the snow. The scarlet of the Phantom’s cape acts like a bloodstain against the monochrome cityscape and Christine’s pale skin, and she rises to an occasion her rival lovers have not earned. She responds to more genuine tragedy than the film provides for her. She has feelings her character must generate from within, and she is so emotionally tortured and romantically torn that both Raoul and the Phantom should ask themselves if there is another man.

I know there are fans of the Phantom. For a decade in London, you couldn’t go past Her Majesty’s Theater without seeing them with their backpacks, camped out, waiting all night in hopes of a standby ticket. People have seen it 10, 20, 100 times — have never done anything else in their lives but see it. They will embrace the movie, and I congratulate them, because they have waited too long to be disappointed. Some still feel Michael Crawford should have been given the role he made famous onstage; certainly Gerald Butler’s work doesn’t argue against their belief. But Butler is younger and more conventionally handsome than Crawford, in a GQ kind of way; Lloyd Webber’s play has long since forgotten the Phantom is supposed to be ugly and aging and, given the conditions in those cellars, probably congested, arthritic and neurasthenic.

This has been, I realize, a nutty review. I am recommending a movie that I do not seem to like very much. But part of the pleasure of moviegoing is pure spectacle — of just sitting there and looking at great stuff and knowing it looks terrific. There wasn’t much Schumacher could have done with the story or the music he was handed, but in the areas over which he held sway, he has triumphed. This is such a fabulous production that by recasting two of the three leads and adding some better songs it could have been, well, great.

Ebert’s Great Movie review of “The Phantom of the Opera” (1925) is online at rogerebert.com. His serial “Behind the Phantom’s Mask” (1993), a murder mystery involving an alcoholic understudy to the Phantom, is nowhere near selling out at Amazon.com.