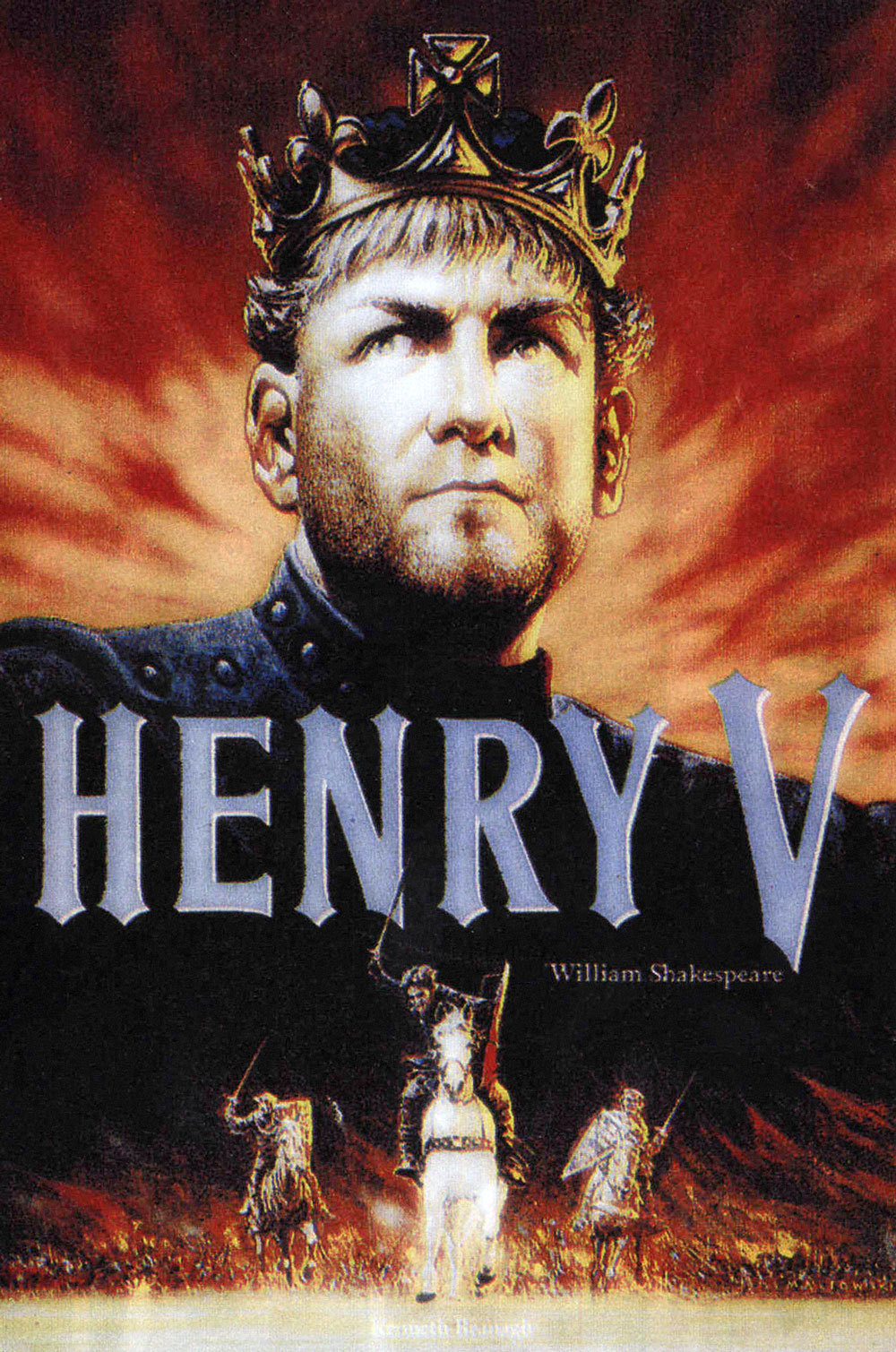

Shakespeare’s “Henry V” is a favorite play of the British in times of national crisis, and in 1944, during the darkest days of World War II, Laurence Olivier directed and starred in it as a patriotic call to the barricades. Perhaps it is no coincidence that another hot-blooded Turk of the London stage, Kenneth Branagh, has directed and starred in this new film version in 1989, as Britain stands poised uneasily on the banks of the new Europe, its toe dipped shyly into the waters of monetary union.

There is no more stirring summons to arms in all of literature than Henry’s speech to his troops on St. Crispan’s Day, ending with the lyrical “We few, we happy few, we band of brothers.” To deliver this speech successfully is to pass the acid test for anyone daring to perform the role of Henry V in public, and as Kenneth Branagh, as Henry, stood up on the dawn of the Battle of Agincourt and delivered the famous words, I was emotionally stirred even though I had heard them many times before. That is one test of a great Shakespearian actor: to take the familiar and make it new.

Branagh is not yet 30, and yet already the publicity machines are groaning to make him into the “new Olivier.” Before his “Henry V,” he had made only one other movie (he was the sunburned young husband in “High Season“), but he has triumphed on the London stage in such talismanic roles as Jimmy Porter in Osborne’s “Look Back in Anger,” and his stock could not be higher. It was a risk to make this film, and it could have been a disastrous failure, but instead it is a success.

That it is not a triumph is because Branagh the director is not yet as good as Branagh the actor. He knows better how to play Henry V than how to get him on and off the screen, and his pacing could be improved. The film begins slowly, bogs down in the seemingly endless battle scenes and then drags to its conclusion through Henry’s endlessly protracted and coy courtship of Katherine.

Branagh himself seems to know that the opening sequences – involving a rebellion in the English court – are in trouble, and he attempts to speed them along with distractingly intrusive music, which only gets in the way of the words. Part of the problem is in Shakespeare, who dawdles with diplomatic matters before getting to the heart of his story, and Olivier dealt with this problem in his 1944 film by facing it humorously. As the French ambassador and others squabble over boundaries and treaties, a frisky wind blows their documents around the stage. In Branagh, all is solemn, and hard to follow.

One of the wonders of Shakespeare’s prose is that, spoken by actors who understand the meaning of the words, it is almost as comprehensible today as when it was first written. In the Olivier film, the actors are better at making the words make sense, perhaps because, for Olivier, clarity of communication ranked above anything else in a performance. Branagh and his actors go for emotion or styles of delivery at the cost of clarity, and so the new “Henry V” is more appropriate for viewers familiar with the play; Olivier’s version was literally intended for everyone.

And yet, these observations aside, Branagh has made quite a film here. His Henry V has a spectacular entrance, backlit and framed by huge palace doors, and is a king from beginning to end (the youthful transgressions with Falstaff are firmly behind him). He is not a tall and dashing king – Branagh looks something like Jimmy Cagney – but he is a brave and stubborn one, and Branagh’s direction wisely goes for realism in the battle scenes. They are not wars of words, but of swords.

The famous British victory over the French at the battle of Agincourt was Henry’s and medieval England’s greatest triumph (although Shakespeare could not resist improving on the facts in the scene where Henry is informed of 10,000 French deaths as opposed to only 29 on the English side). In the film, Branagh seems determined to account for every French death, and the battle wears on, steel against steel and horse against man, endlessly. There is too much of it – as if, having spent the money for all of those extras and all of those costumes, he wanted to get his money’s worth. And yet, at the end, when the exhausted king confesses, “I know not if the day be ours or no,” we share his exhaustion and his despair at bloodshed.

Branagh’s approach depends on blood-and-thunder, as opposed to Olivier’s insouciance. Even though Olivier made his film in the midst of a world war, it is probably true to say that we live in a more violent time today. Certainly our films are more violent, and in a sense Branagh is only keeping up with the state of the art when he soaks his battles in blood and mud. What happens as a result is that the scenes in court seem to exist on a different level of reality – especially the long scene of flirtation and proposal between Henry and Katherine, which ends the film. We have seen so much real blood that we have no patience for social gamesmanship, and the movie would probably play better if Henry had simply swept Katherine into his arms and forgotten the elaborate phrasemaking.

What works best in the film is the over-all vision. Branagh is able to see himself as a king, and so we can see him as one. He schemes, he jests and he deceives his soldiers during his famous tour of the field on the night before the battle. In victory he is humble, and in romance, uncertain. Olivier, who was 37 in 1944, wrote that Henry V was the kind of role he couldn’t have played when he was younger: “When you are young, you are too bashful to play a hero; you debunk it.” For Branagh, 29 is old enough.