Writer-director Angus MacLachlan’s “A Little Prayer,” about a family in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is like a beautiful hand-wrought sculpture that’s small enough to fit in your palm. Making it bigger would not have made it better. It’s perfect just as it is.

Bill (David Strathairn) and Venida (Celia Weston) reside in a modest house in a quiet suburb, surrounded by tall, old trees that form a canopy over the streets. Venida has a day job as a docent giving tours of Old Salem, a historic district. Bill is a Vietnam War veteran who founded and still runs a local sheet metal factory. In the winter of their lives, they are still taking care of their children, who have grown into adults with adult problems.

Bill’s son David (Will Pullen), who served in Iraq and now works as a manager at his father’s factory, lives in the guest house behind his parents’ place with his adorable wife Tammy (Jane Levy). Soon enough, David’s younger sister, the manic and vulgar Patti (Anna Camp), shows up with her young daughter Hadley (Billie Roy), who’s cute but kind of a terror, and says she needs a place to live because she’s leaving her rotten husband. It is not the first time she’s done this.

He and Venida didn’t expect an empty nest to fill back up, nor did they expect their lives to be dominated by dramas they had nothing to do with. Nevertheless, here they are, dealing not just with Patti’s crisis and the expense of two additional residents, but problems in David and Tammy’s marriage as well. The problems are David’s doing. He stays out late several nights a week, telling Tammy he’s putting in overtime when he’s actually cheating on her with an employee, Narcedalia (Natascha Polanco). Venida is oblivious to the affair, and it seems as if Tammy is as well. Bill deduces that it’s happening by observing David and Narcedalia’s body language, which all but screams, “They’re doing it!”

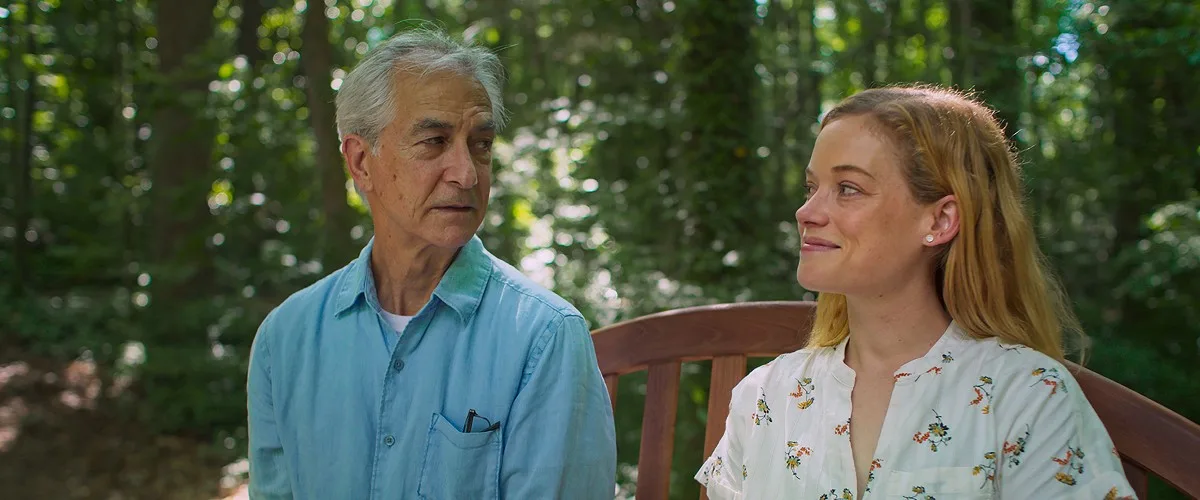

What does a father of Bill’s vintage do with such knowledge? He wants his children to be happy, but he also wants them to conduct their lives with honesty and good judgment. And he adores Tammy, a charming young woman who’s a ray of light in his life. Then he gets another piece of information that he wishes he’d never heard, and it hits him even harder.

This sounds like the synopsis of a screamfest with slammed doors and broken plates. But that’s not what “A Little Prayer” gives us. MacLachlan keeps things delicate and hushed, rarely letting the temperatures of even agonizing moments rise above a simmer. He’s telling a story about the sorts of people who are more likely to implode than explode, or at least keep their detonations private.

The film is refreshingly content to present its characters in their complexity and contradiction, and ask that we accept them in totality rather than condemn them for their sins. David has no obvious reason to cheat on Tammy, but he’s doing it. Later, we get information suggesting that his infidelity is just one manifestation of a psyche that’s been in turmoil since he returned from Iraq; it’s not exculpatory, but it does make him something other than a rat husband. And it shows that he’s part of an endless cycle. There are multiple scenes set at a Veterans of Foreign Wars hall where the factory employees go each Wednesday after work to drink and dance. At one such gathering, Bill asks a fellow Vietnam veteran why a mutual friend hasn’t come to the VFW hall yet, and is reminded that certain people emerge from that kind of experience never wanting to talk about it again. Neither approach is endorsed as being correct.

This is the kind of movie where you’re on everybody’s side, because life is hard and nobody’s perfect and none of these characters are irredeemable and you wouldn’t wish suffering on anyone who’s just out there doing the best they can (maybe on anyone, period). There’s a moment where a couple of lines of dialogue make us wonder if Bill is no saint, either, and his agitation over others’ bad choices is really about guilt over his own failures. Just when you start to root for one character against another, the movie provides a bit of information about the second character that softens your attitude and prompts you to consider your own imperfections.

Even Narcedalia is treated fairly. She’s not a caricatured “other woman,” but a full person with friends and an apartment and a past life. There’s a long scene late in the movie might make you respect her willingness to be honest about her own misjudgments and choose a path that will make something positive from them.

Like MacLachlan’s breakthrough script for 2005’s “Junebug,” “A Little Prayer” has a religious, specifically Christian, dimension that’s woven into the drama rather than superimposed onto it. The movie opens at dawn with the camera traveling through the lush green neighborhood where the family resides. A woman’s voice sings gospel on the soundtrack. It is loving, transcendent, and loud. Some in the area find the singing annoying. Bill and Tammy like it. Bill even asks Tammy to join him in a search to find the singer and introduce themselves.

That’s not as easy as it sounds. That heavenly voice might be a stand-in for a God whose presence seems undeniable at times, but that is more often elusive or invisible. You can’t chase God. God either manifests or doesn’t. Gliding shots of the trees shading houses at dawn as an unseen, unknowable voice sings the morning gospel evokes Terrence Malick’s cinema. The commonality that links all Malick’s films is the palpable presence of a cosmically unifying energy that we are encouraged to think of as a higher power. The poetic voiceovers are prayers of a sort, offered to a presence that always hears but doesn’t always act, or that acts contrary to one’s wishes. Malick’s movies, to quote a piece by David Roark that was published here in 2016, “function as cinematic liturgies that paint a distinctly Christian picture of the good life—the kingdom of God—reflecting the gospel story of creation, fall, redemption and restoration.”

Roark calls Malick’s movies “liturgical.” But where Malick’s movies are as grandly ceremonial as a baptism, a wedding, or a mass, this one feels more like a private prayer asking for guidance in rough times. This movie’s title seems like a tribute to Malick, whose films inspired this site’s founder, Roger Ebert, to write one of his most vulnerable essays, “A Prayer Beneath the Tree of Life,” about Malick’s 2012 epic. “I value the kind of prayer when you stand at the edge of the sea, or beneath a tree, or smell a flower, or love someone, or do a good thing,” he wrote. “Those prayers validate existence and snatch it away from meaningless routine.” This movie does the same thing.

Everyone will have their own take on the film’s theological dimension. Mine is that Christianity, like most forms of spirituality, is ultimately about striving to reach a state of grace, not because it is objectively achievable, but because it the effort itself is ennobling and redeeming. It keeps us moving forward, trying to better ourselves and repair any damage we caused, which in turn makes a cruel world more bearable. Bill is given burdens that he didn’t ask for. He repeatedly asks permission to offload the burdens onto others, because their weight is crushing him, and it feels wrong to keep secrets from those he loves.

The Bible presents multiple ways of looking at Bill’s problem, many of them contradictory. It’s not as if you can add them all together and divide by the total number of Bible quotes to get a spiritual average that can steer you towards the right choice. The multiplicity of angles from which people contemplate their lives, and other people’s lives, is another one of the movie’s dimensions. There will probably be at least one subplot in this film that captures something you have experienced, or that happened to someone you know. Learning that your own problems aren’t unique and feeling not trivialized but consoled by this realization is another glorious side benefit of the moviegoing habit, along with surround sound, trailers and hot buttered popcorn.

In one scene, Venida brings a tour group to God’s Acre, an 18th-century Moravian cemetery. Moravians, she says, believe that whatever our status in life, “we are all the same in death,” and that when you die, you should not be buried with your family, but “in the order in which you died.” If you bring humility to the contemplation of death, as the Moravians have done in burial practices, you recognize it as the great leveler. It doesn’t matter if we’re buried in a lavish crypt or in a mass grave; we still turn to dust. If we are remembered at all, it’s for the good or bad that we did. The older we get, the more time we spend hoping the good outweighs the bad in the eyes of those we leave behind.