There’s a memorable scene in John Hughes’ 1986 comedy classic, “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” where awe-struck teen Cameron (Alan Ruck) glances at George Seurat’s infamous 1884 painting, “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” that still hangs to this day at the Art Institute of Chicago. The film cuts back and forth between increasingly close shots of Cameron’s face and the painting itself as he realizes that Seurat’s pointillist artistry seamlessly blends countless dots of differing colors, none of which are readily apparent when the image is viewed as a whole. I can’t picture a better metaphorical portrait of the craft mastered by editor Paul Hirsch, who has seamlessly woven together an untold number of impeccably chosen shots to form some of the finest and most beloved films ever made. His father was a painter while his mother was a dancer, and the intuitive essence of both art forms has profoundly enhanced his approach to editing.

In addition to “Ferris Bueller,” Hirsch’s credits include “Sisters,” “Phantom of the Paradise,” “Carrie,” “The Empire Strikes Back,” “Blow Out,” “Creepshow,” “Footloose,” “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” and “Steel Magnolias,” along with the first and fourth installments of the “Mission: Impossible” film series. In 1978, he joined his colleagues Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew in accepting their Oscar for editing “Star Wars,” and in 2004, he was nominated again for Taylor Hackford’s rousing biopic, “Ray.” He insists that the uproarious bonus scenes following the end credits of his John Hughes pictures—which are emulated throughout the Marvel Cinematic Universe, not to mention parodied in “Deadpool”—were entirely the idea of the director himself, though there’s no question that Hirsch’s sense of pacing and comedic timing are a crucial part of why those films are so agelessly funny.

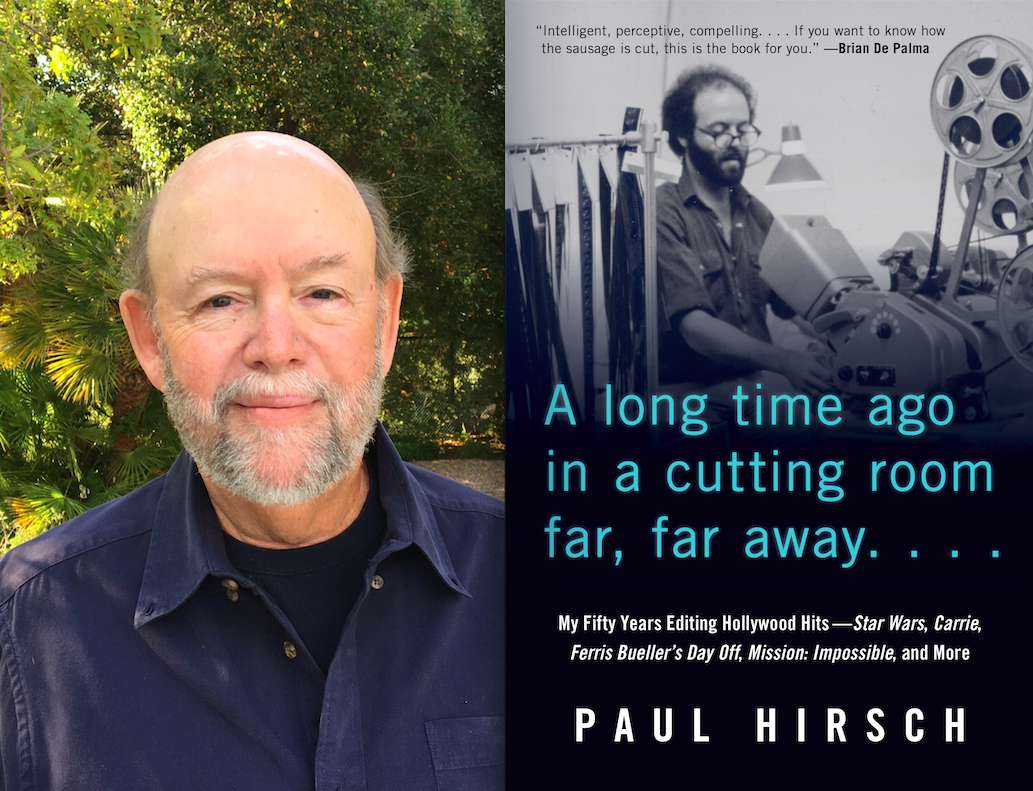

For many fans of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” the poignant comedy about mismatched travel companions Neal (Steve Martin) and Del (an Oscar-worthy John Candy) scurrying home for the holidays, watching the film around Thanksgiving has become an annual tradition. Roger Ebert’s family made the film a cherished part of their holiday viewing, as did my own, so it was a great pleasure for me to attend last Wednesday’s special screening of the movie at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, where it brought down the house. James Hughes, son of John, accompanied Hirsch onstage for a Q&A afterward, and it was clear that the audience’s euphoric response to the picture had warmed the heart of its editor. A few hours prior, I traveled on the same L train line ridden by Martin and Candy in the film to speak with Hirsch at the offices of the Independent Publishers Group, which recently released his acclaimed memoir, A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away…

During the following conversation, Hirsch discusses his approach to editing some of the most unforgettable sequences in “Carrie,” “Star Wars,” “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” “Blow Out,” “The Empire Strikes Back” and “Ray,” many of which contain spoilers, so if you haven’t seen any of these titles, you have some quintessential viewing to prioritize this weekend.

Let’s begin with the greatest jump scare in film history, which concludes Brian De Palma’s “Carrie” (1976), where the hand comes out of the ground in a surreal, dreamlike shot. Roger Ebert deemed it the best cinematic shock since the shark leapt out of the water in “Jaws.”

Brian designed that moment, and of course, my contribution was figuring out how to put it together. For me, music has always been an essential part of making non-dialogue sequences work. In that particular case, I tracked the cut that I did with two pieces of music—one was Tomaso Albinoni’s “Adagio in G Minor for Strings and Organ,” which is now attributed to Remo Giazotto, and at the moment of the jump scare, I used the opening notes of Bernard Herrmann’s Main Title for “Sisters,” which I had edited. It begins with an anvil strike, and it was that sort of sudden percussive metallic sound that makes people jump as much as anything else. We asked the film’s composer, Pino Donaggio, to reproduce that and he did. It’s funny, when I look at the scene now, it doesn’t seem like a visually startling moment because it’s sort of gradual. It’s not a sudden motion, and the footage may have been slowed a bit.

I’ve found it interesting that no one ever questions why all these stones are lying in that pit where Carrie’s house has collapsed. There used to be a sequence at the very beginning of the movie in which we see Carrie as a little girl looking through a picket fence at a teenage girl sunbathing next door. Carrie comments about her “dirty pillows,” and the neighbor says, “What do you mean, ‘dirty pillows’? You mean my breasts?” Carrie answers, “That’s what my momma calls them,” and then you hear Margaret White’s voice from inside the house calling her in, saying, “Come in here this minute, stop talking to that girl!” Carrie becomes terrified, and at that moment, small stones fall out of the sky onto the roof of the house. Brian shot this faithfully, but the small stones didn’t read as gravel onscreen, they read as water. The action ended up not making visual sense, so we decided to eliminate it.

However, Brian had already shot the destruction of the house with the rocks coming through the ceiling, and they are still in that sequence, but somehow, the audience seems to ignore them. Nobody questions where these rocks come from. On the night when they shot the house collapsing, the conveyor belt that was supposed to dump the rocks onto the roof jammed. They couldn’t get it to work and the sun was beginning to come out, so Brian finally said, “Forget the rocks, just light the thing on fire.” It was a miniature house that was placed on a lift, so when they lit it on fire, it could be lowered mechanically into the pit. And yet, in the end sequence, we still had all these stones in the pit, because that was the plan.

That scene illustrates how a jump scare doesn’t have to come from a cut, but from holding on a sudden, unbroken movement. I’ve viewed it on a small television in a brightly lit room, and it still makes people jump.

[laughs] I think that’s because it’s unexpected. You think that everything is over, and you’re not expecting movement from the grave. This is analogous to a lesson I tried to impart to editors who are still learning that in cutting to music, for instance, it’s very tempting to cut on the beat, or cut to the beat of the music. But I prefer to cut in between the beats, so that the beat lands on some of the action in the shot instead of on the cut. You let the music animate the action instead of animating the cuts. I did a movie called “The Fighting Temptations,” and it featured a gospel chorus led by a very charismatic choir leader who made big gestures with his hands. If I had cut on the beat, I would’ve missed the upward swoop of his arm before the downbeat. So you don’t cut on the downbeat, you cut before so you get the action going into the downbeat. That’s the idea, and it’s similar to the jump scare. You don’t cut on the moment, you cut before the moment so the moment can land.

Whereas so many modern action sequences drift into incoherence, the climactic attack on the Death Star in 1977’s “Star Wars” never allows you to lose track of each rebel fighter. Each of their deaths chips away at our sense of certainty that victory will be achieved.

That was all Marcia [Lucas]. She had spent many months building the sequence, and we had to finally edit it down and lock it in. Toward the end, we divided the sequence in two. She edited the section up to when Red Leader [Drewe Henley] crashes onto the surface of the Death Star, which also signals the return of the music. From that point on, the sequence was given to me. I edited Luke’s trench run that ends with the explosion of the Death Star, while Marcia worked on the first two trench runs as well as the set-up for the whole thing. So we worked separately for a while, and then when it got down to crunch time, we had to quickly deliver the final cut to ILM because they needed months and months of time to accomplish all these shots.

We did a sort of tag team session where either Marcia or I would “drive” the edit, while the other person would sit on the couch next to George [Lucas]. I’d edit for a couple hours, and then Marcia would take over. After about two or three days of that, we locked the sequence, all without John Williams’ score. I use music sometimes if I’m cutting a montage, for instance, and I need some help to find the rhythm or the structure. But other times, I’m following an internal clock and a sense of pacing and tempo that is instinctual. The music comes later.

Was it always storyboarded that Han would suddenly materialize to save the day?

Yes, it was storyboarded and figured out way in advance. For a long time, we didn’t have the shot of the Millennium Falcon flying in with the sun behind it. All we had was a piece of leader, and Marcia had scribbled on it with a Sharpie, so when it appeared on the screen, there was a shot of crazy abstract forms inserted in place of the Falcon. Marcia just estimated the length of the shot in the context of the sequence, and she was very concerned about whether the moment would work. I kept assuring her that it would.

She had gone off to work with Martin Scorsese on “New York, New York,” and came back for a screening of the now nearly finished film. George asked her to clear a week of her time so that we could make changes after the preview. By that time, we had been over the picture so many times that I said to George, “Why do you think that we’re gonna need a week to make changes?” He responded by voicing his belief that previews always mean changes. Then we previewed the picture and the audience was spectacularly enthusiastic. We came out afterwards and I asked George, “Well, what do you think?” He said, “I guess we’ll leave it alone.” [laughs]

Tonight will be my first time seeing “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” with an audience other than my family.

Oh my god, it is such a good audience picture. When it cuts to that frozen dog sitting next to Neal and Del, it always gets a huge laugh.

In his Great Movies essay on the film, Roger Ebert discussed the power of watching Candy’s face fall during Martin’s meltdown in the motel. You strike such a complex tonal balance in the sequence, toggling between hilarity and genuine pain.

It’s very cruel what Steve is doing, and having a character be that cruel while still retaining the audience’s sympathy is a very fine line to walk as an editor. That was the tightrope we were walking throughout the picture. We wanted to keep the characters sympathetic, and Candy was great in that sequence. The decision of when I should cut to the big close-up of his face was carefully thought about, as was the inclusion of a moment in Candy’s response where he stumbles a little. Candy was just masterful. He would memorize pages and pages of dialogue every night, and in this one instance, he stumbled and had to repeat himself. It worked because you get the sense that Del’s overcome by emotion, and is mastering his feelings at that moment.

It’s a very powerful scene—funny but not funny, and very revelatory about the characters. Looking back on it, I think there’s something to be learned for us today in the characters that Neal and Del represented. Pairing them was sort of like “white collar meets blue collar.” That divide was present in the country thirty years ago, and has become even more rampant today. The wonderful thing about the picture is that it ends on a positive note where these two guys are able to get past the differences between them, find a common humanity and form a friendship. I wish I felt that optimistic about the country today.

I felt that last year’s Best Picture winner “Green Book” was evocative of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” particularly the final scene where Dr. Shirley (Mahershala Ali) is invited to have dinner with the family of Tony (Viggo Mortensen).

I frankly hadn’t thought about it before, but I see what you mean. There are so many influences out there that you don’t know exactly what picture triggers what, but that’s a legitimate comparison. I personally thought it was a wonderful picture, but a lot of African-Americans felt differently. Many viewers refused to accept that any African-American needs to be taught how to eat fried chicken.

A writer at our site wasn’t happy about that either, and that’s the good thing about film discourse in how it illuminates differing perspectives.

Yes.

Your sense of comic timing is unforgettably demonstrated by Martin’s symphony of F-bombs directed at the perky car rental attendant (Edie McClurg).

When I was working on “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” John [Hughes] came in one morning with a manilla envelope and handed it to me. I asked what it was, and he said, “The first sixty pages of my next picture, you want to cut it?” So I read it and it included that scene. He had written it in one draft in one sitting the night before. He sat at the typewriter for around ten hours, writing six pages an hour. He could write almost as fast as he could type for sustained periods, and those first sixty pages he had written of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” never changed. They included that scene, and I tell you, it was as funny on the page as it was in the shooting. As for how to approach cutting a scene like that, you just follow your instinct. That is all I’ve ever really relied on. You can’t research this sort of skill, and you can’t learn it. You just have to feel it. If you have good instincts, you’ll do well, and if your instincts are not good, you won’t. All any of us in the business have to rely on is our instincts.

You’ve mentioned how interspersing the flashbacks throughout “Ray” enhanced the film considerably, and it reminded me of how you utilize flashbacks in the final scene of “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” where Neal sits on the L, anticipating Thanksgiving while recalling his time with Del. Its method for revealing the plot twist regarding Del’s wife, Marie, predates the similarly structured endings of “The Usual Suspects” and “The Sixth Sense.”

That sequence was a result of desperation, because as originally written, the scene was quite different. In the original cut of the film, after Neal and Del part ways on the elevated platform in the city, Neal gets on the train, travels out to the suburbs, walks into the station and trips over Del’s trunk again. He looks up and Del is sitting there. Neal exclaims, “Del, what are you doing here?”, and he says, “Well, I got one of the truck drivers to give me a lift.” So Neal goes, “No, what are you doing here? Why aren’t you home?” Del replies, “I have no home. Marie died eight years ago.” Then he launches into a big explanation of how he has a hard time during the holidays and often latches onto somebody like he did with Neal. He tells Neal how great of a guy he is and that it was a real pleasure traveling with him, before revealing that he occasionally spends his holidays at churches.

As he’s telling this sob story of his life, the audience at preview screenings started to laugh, and they were not a good laughs. The longer he went on describing Marie and how he carries her around with him, the audience was laughing more and more, and we thought, ‘This is horrible.’ So we had to cut the scene, while under the pressure of the fact that we needed to have the cut delivered yesterday. The film would soon be opening in theaters, and we needed to have the cut ready so it could be mixed. New releases were still on film in those days, so mixing didn’t happen as quickly as it can today.

When you’re working 12-to-14-hour days for weeks on end, it’s hard to track who thought of what, but what we ultimately came up with was the notion of Neal on the train thinking back and reflecting on his journey with Del. There was a take of Steve making various expressions, and we spliced in little moments that hinted at Del’s situation so that Neal could figure it out from these hints. We had one shot of the train leaving the L station, and we ran the film backwards so that the train seems to be arriving at the station. Then we took a shot that we had of Steve jumping off the train that was originally meant for him hurrying home, and we flipped that so instead of going from left to right, he was going from right to left into the L station. The interior space where Neal finds Del was actually the suburban station. We had never seen the interior of the city station, so we played that as if it were downtown.

That’s why it looks so cozy! [laughs]

Del’s one line about his wife turned out to be all the audience needed, and then we cut to Neal bringing him home for Thanksgiving dinner. It was much better for Candy’s character, because he wasn’t throwing himself in front of Steve and begging for kindness. He maintained his dignity. And it was better for Steve’s character because he had enough empathy to figure out what was going on and put it together on his own without having to be told. So it was a case of desperation producing inspiration, and that was what came out of it, but it was in no way planned originally.

My eyes always well up when Del looks at Neal’s wife coming down the stairs, and you cut to a shot [pictured above] of him gripping his hat, suggesting that he’s remembering Marie in that moment. A simple cut like that can get us closer to the character’s emotional experience.

I’ll make sure to look for that shot tonight. Neal’s wife was originally supposed to believe her husband had made up his stories about Del, and that he was actually having an affair. That lent a greater sense of relief to the moment when she sees Del for the first time. We experimented with the ending over and over during our nine previews held that year in September. We previewed it so often that one of the cards we got from an audience member was, “I like the other ending better.” In one version, the film ends with the family all seated at the dinner table, and water is running down the wall behind Neal. He asks, “Where’s Del?” and his wife says, “He’s upstairs taking a shower.”

For its 35th anniversary, we screened De Palma’s “Blow Out” (1981) at Ebertfest with Nancy Allen in attendance. Were there many thematic discussions between you and the director regarding how to evoke Chappaquiddick without being too overt?

That was a difficult one. We had discussions, but Brian and I were not entirely in sync on that picture. He had been inspired to write it by working with a sound editor on a couple of pictures, and he was fascinated with the idea of somebody going out with a microphone recording sounds for a movie. Of course, it’s based—loosely or tightly, however you want to look at it—on “Blow Up” by Antonioni, in which a photographer accidentally photographs what he believes to be a murder. In this case, it was John Travolta accidentally recording what he believes to be a murder, and so the similarities are there. You’re right about it being a political commentary. Since the story involved a campaign, the production designer used red, white and blue motifs throughout the picture.

I had thought that the final pursuit, where Travolta is tracking Nancy’s whereabouts, would’ve been more interesting if they had gone through, say, an amusement park. The various booths or rides would create interesting and distinctive sounds so that he could use his hearing as a way of tracking them, but instead, Brian wanted to do it in the subway, which is just noise. I suppose an argument could be made that it’s better for Travolta to be confused by the absence of any distinguishable sounds. Look, Brian’s the director. Editors make suggestions, and many of my suggestions he was quite happy with, but he wasn’t interested in that one. He also had some issues with the climactic chase. When I had Travolta plunging into the crowd after John Lithgow has taken Nancy Allen up to the top of the stairs, Brian felt I was doing it too soon, so he had me delay it. Then the producers saw it and said, “No, you’ve got it wrong, it needs to start earlier,” which is where I’d had it.

The thing about cutting on film is it’s not easy to save a version. You have to send it out in order to make a copy, thus leaving you without your work print for a day or two. And it’s an expense, so usually what’s done is you take apart the version you have and replace it with a new version. This is, of course, distressing for the editor who is losing the version that he believes in to make a version that he doesn’t believe in, and then to be told to put it back the way that it was. You can never really remember exactly how it was. Then there were structural problems with the film because Lithgow’s introduction, as it was originally scripted, came too late, so there was an absence of tension in the first part of the movie. We started moving scenes of Lithgow up forward earlier in the continuity, and that created another ripple effect where we had to take one of the scenes between Nancy Allen and Dennis Franz and cut it in half. We used half in one place and half in the other.

The script was not as far along as it should’ve been, and there were flaws in it that we didn’t perceive, but it ended up working out. When we finished the film, I saw it in the Hamptons, and people booed at the end of the movie. I never saw an audience so angry. They were very upset that Nancy was killed at the end, and I even had a solution for that which Brian rejected. We get to the mix as they’re playing back the scream, and the director says, “Now that’s a scream!” Then we cut to Travolta and pan over to see Nancy with a bandage around her neck. She smiles at him and he smiles at her and everything’s fine. Brian didn’t want to have that. She had to be dead. The audience hated it, but now, after several years have gone by, the film is celebrated as a real cult favorite. The release of a picture is like its birth, and then it grows up. Sometimes it grows up and ends up forgotten, but sometimes it grows up to be a prominent member of the community, so you never know.

Everyone forgets that audiences originally didn’t fully embrace 1980’s “The Empire Strikes Back” because it didn’t have a crowd-pleasing ending. That film remains the gold standard for any epic blockbuster juxtaposing parallel narratives.

Larry Kasdan had that all laid out in the script. We locked that picture one month after the end of shooting, so there wasn’t a lot of fooling around. The structure as it was designed worked, and it went very smoothly. It was also very daring to make that picture. Faced with the huge success of “Star Wars,” the temptation was enormous to make another version of the first film—in other words, you have some adventures and it would end in a big battle where the good guys win out in the end. George did not do that. He decided to put the big battle at the beginning of the movie, and then end the film on an unresolved note, which was extremely bold and risky. I don’t think we got enough credit for that. In fact, the picture did not do as well as the first one, and it did not do as well as the third one either. People want resolution, and it was unsatisfying for audiences, but it was always meant to be Act II of a three-act story—the middle trilogy, as it were—so it was a very courageous decision to do it that way.

How did your collaboration with Brian De Palma on his Hitchcock-influenced pictures help mold your approach to editing suspenseful sequences, such as the Mynock attack in “Empire” [embedded above]?

Brian hugely influenced my perspective on film. I didn’t go to film school, and I never studied editing. My process of learning the craft was similar to how art students sit with an easel in front of an old master’s painting at a museum and try to copy it. That was my approach to learning editing. I would see things in movies that I had admired and I tried to do the same thing with the dailies that I was presented with in my work. But Brian was a big influence, even on “Star Wars.” There’s a sequence that I’m particularly fond of, which is when Vader strikes down Obi-Wan. At that point, our characters—the droids, Han and Chewie, Luke and Leia—have been split up, and they come together at this moment when Obi-Wan is battling Vader. All these paths of all these different characters are coming together both physically and geographically.

It’s important to note that I wasn’t the editor from the start on “Star Wars,” so I was looking at already edited film. I was presented with this sequence that just did not work, and I thought, ‘How can I fix this?’ What I relied on were things that I had picked up from working with Brian. I would choose shots of characters looking around, and then I’d cut to an angle that would be from their point of view. By using various shots of stormtroopers—running in pursuit of the heroes—to represent the characters’ perspectives, you could tell that they’re all occupying the same space. Once you’ve established that they’re in the same space, then you had to show the various elements of these three story strands coming together—four, if you include Obi-Wan and Vader. They had to mesh timing-wise, so that was a little tricky, but it’s also a very emotional moment, maybe the most emotional moment in the series. Ben’s death is comparable to when Luke learns who his father is in “Empire.” But the looks of characters, their perspectives on the action and their reactions to what they see are attitudes I picked up from working with Brian.

It’s an excellent example of how to pace an action sequence without losing the audience’s emotional investment.

The trick for editors is to look at footage with the same critical eye one uses when playing that game, “What’s Wrong With This Picture?” Well, there’s a cow on the roof, and cows don’t belong on roofs. When you watch your movie, you sensitize yourself to what shouldn’t belong in the frame. You look for things that are wrong with it, and try to fix them. One of the things that you have to pay attention to is whether a scene is moving too slowly or too quickly, and whether the moments are landing. You have to be sensitive to that, and you have to find the right balance between too fast and too slow, so that the audience is always engaged and the picture is moving forward, but not so fast that the moments that matter don’t land. That’s the trick.

Was your approach to cutting Yoda’s sequences no different from those featuring any other performer?

My approach to cutting character sequences is no different, whether the character is played by an actor or an actor through a puppet, and Frank invested the puppet with a great personality through his voice and his movement. There were four people operating Yoda—one guy was doing the ears, another guy was doing the forehead—and they all had different controls. Frank had his hand up inside the puppet, while operating from under the floor. They had a floor built up so that Frank could get underneath and reach up while watching himself on a video camera to see what he was doing. It’s an elaborate technical feat, but what brings the character to life is the coordination of the puppeteers and the voice. “Animation” is based on the latin word for soul. When you animate something, it brings its soul to life.

And that’s what you do as an editor, finding the soul that links the fragments. “Ray” has such an infectious soul that the audience at my screening in Chicago were dancing during the musical sequences, just like Candy does in the scene set to Ray Charles’ “Mess Around” in “Planes, Trains and Automobiles.”

That song was John’s choice. I love Ray Charles’ performance of “Shake a Tail Feather” in “The Blues Brothers.” Cutting to music is something I greatly enjoy. You wouldn’t know it looking at me now, but I used to be a really good dancer when I was young, and my approach to editing is like that of a dancer. You listen to the music and decide what to do once you hear the music. It’s an interpretive art, just like editing. You hear the music and you decide how to dance to it, and it’s the same thing with dailies. You look at the dailies and go, ‘How am I gonna dance to this?’

Do you find yourself moving at all when you’re editing?

Nope, I’m very lazy. The work is so absorbing that I sat down to work one day, and when I looked up, forty years had gone by.

Speaking of intuitive creative processes, your editing wonderfully captures the spontaneity of Ray Charles creating “What’d I Say” on the spot [embedded above].

The original live performance recording was used as playback, and Ray had started out singing off-mic. So Taylor invented this gag at the beginning of the piece where Ray had pushed away the microphone and then he reaches for it and pulls it over when he begins to sing. After he realizes that it’s facing the wrong way, he turns it toward him. That action was staged and dictated by the real recording, so it justified what we’re hearing. This sort of detail makes the sequence feel real, as if it’s happening before your eyes.

What was it like exploring your career through this memoir?

When I began working on the book, I thought that I wouldn’t write it chronologically because I assumed it would be boring. So I started writing it out of order, but then I found myself having to keep backtracking and backfilling, providing context about how I had met various people on previous pictures. It was pointless and boring for me to explain how I had already known these people, so I changed my mind and wrote it chronologically. Then my agent told me that I had to get to “Carrie” within the first fifty pages. The challenge was that it was coming in around eighty or ninety pages at that point, and I didn’t think I could cut forty pages out of the book, since that’s the part that people always ask me about, the question of how I got into the business. My editor, Jenefer Shute, came up with the idea of me starting with “Carrie” and then going back to the beginning, so that’s what we did. It was a really good suggestion.

Other than that, the book is pretty much chronological, which makes sense because it illustrates the arc of the career, the ascent as well as the descent, which is why they call it an arc, along with my changing attitudes as I aged. You see things differently at certain points of your life. I alternate between thinking that these are really good stories and that this is the most narcissistic thing that a person can do. But I wanted to share my experiences with people. It’s not meant as a how-to book, which I consider to be boring. So many people have access to the editing tools now that most readers will be familiar with the editing process, so I didn’t want to start teaching how to edit, although there are some insights I picked up that might be useful to people. Above all, I wanted to entertain. I’ve been in the entertainment business all my life, and I wanted to write a book that was as entertaining and amusing as it was informative. So far, people seem to be reacting positively to it, which is very gratifying.

I find myself using the same instincts when editing that I do while writing, taking all the raw footage—either in my brain or on the screen—and assembling it.

With writing, you are the director and producer as well, but the editing process is pretty much the same, whether you are working with film or words. Editing a book felt very familiar to me, particularly the part where I get notes from other people. Your first reaction is, ‘I’m not going to do that,’ and then you think about it and you say, ‘Well, maybe there’s a way I could make this work.’ I enjoyed editing the book. I had a lot of help and a lot of good suggestions, but ultimately, it was up to me. I was the one making the decisions this time, so this is my “written and directed by.”

A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away… is available for purchase at the official site of the Independent Publishers Group.