The premise for Francis Gallupi’s directorial debut, “The Last Stop in Yuma County,” feels like it’s setting up a long-winded joke: a traveling knife salesman, two bank robbers, a traveling elderly couple, and two wannabe criminals walk into a diner while waiting for a fuel truck to arrive. Although some characters wear their menace on their sleeve, what keeps the film so unsettling is how little we know about each person who comes into the diner. The presence of the bank robbers’ money in proximity to individuals desperate for reinvention only increases the stakes. What ensues is a tense and bloody stand-off of the highest order, and Gallupi masterfully knows when to build on the tension he’s established in this chamber piece and when to release it through colorful and brutal spurts of violence.

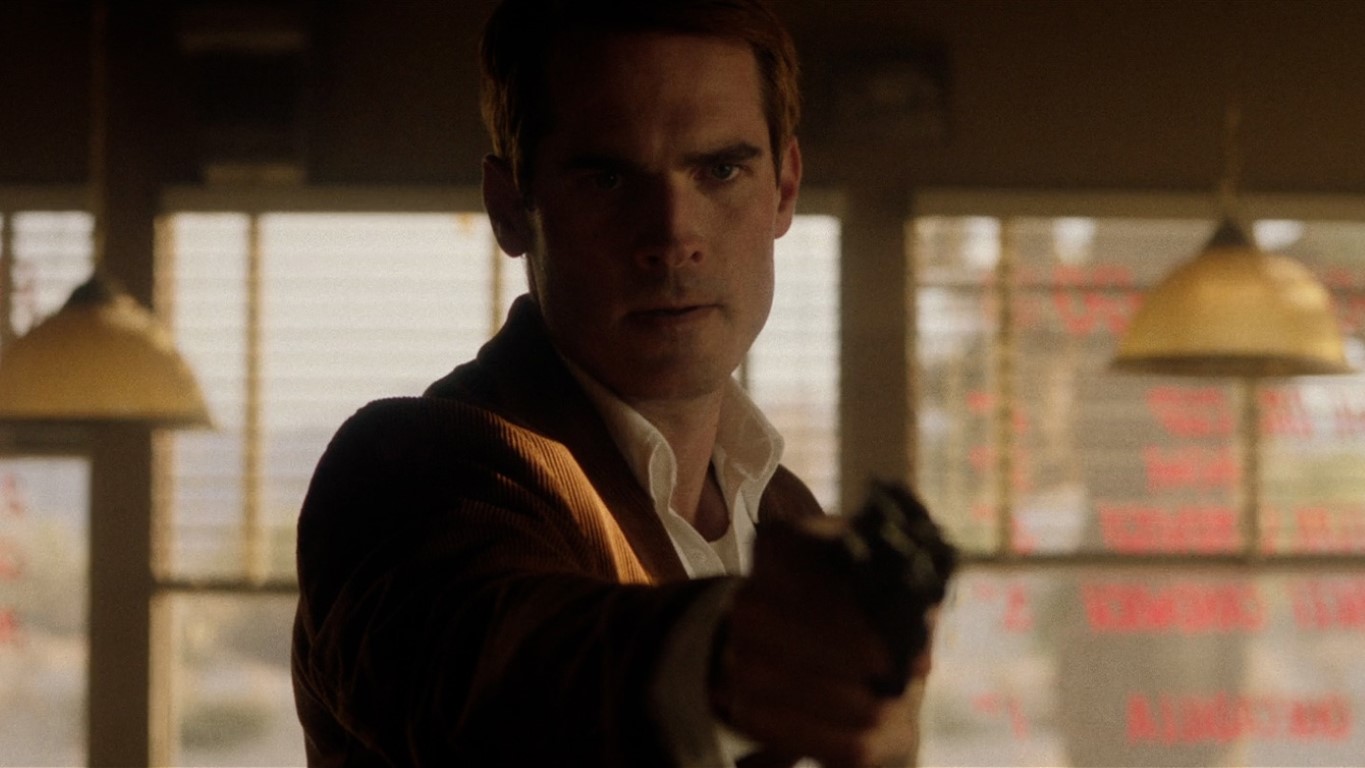

Actor Jim Cummings plays the conniving and unnamed knife salesman. It’s a brilliant balancing act where he is the audience’s eyes and anchor in the midst of the carnage. But there are inklings of belligerence that simmer just below the surface, adding to the long tradition of “cinematic dipshits” (as a Letterboxd member put it) he has played, from “Thunder Road” to “The Wolf of Snow Hollow.”

Put more eloquently, Cummings has carved a lane by deconstructing the powerful and privileged characters he portrays; we can laugh at them rather than with them. Cummings believes that laughing at despicable characters is one of cinema’s greatest gifts. “When you laugh, you subvert the status quo of power dynamics of who is in charge,” he shared.

He spoke with RogerEbert over Zoom about the role of humor in challenging authority, what the animals in “The Last Stop in Yuma County” ultimately symbolize, and his excitement and hopes for Gallupi’s take on the “Evil Dead” franchise.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I keep telling people that The Last Stop in Yuma County is going to give Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga a run for its money as the desert movie to dominate May.

Jim Cummings: (Laughs) That’s lovely. Thank you.

The film is also playing in Chicago as part of the 11th Chicago Critics Film Festival.

That’s right! Over at the Music Box!

I already know Midwesterners will feel very seen by the inclusion of rhubarb pie in the film.

I love that line in the movie where they’re selling how good the rhubarb pie is and Sierra McCormick’s character goes, “It’s not that great.”

Had you heard of or eaten rhubarb pie before?

Oh yeah.

The way your character fumbled his way through the pronunciation convinced me that you’d never heard of it.

(Laughs) Yeah, I’m from New Orleans, Louisiana, and I grew up with a bunch of bakers, so I’m well versed in rhubarb.

You’ll have to give me good New Orleans recs if I ever go down there.

Oh yeah, I’ll send you a map. I have a map I send to friends, on which I tell them where the great places are and which ones are too touristy.

I would love that. I heard that Francis wrote letters to the people in the cast that he wanted to be in the project. What did he write in your letter, and how did this story and project come to you?

He wrote a very respectful letter about me influencing him to get off the couch and make things. His background was in music. He played drums for a band called Guttermouth for many years, and then he transitioned into directing music videos, commercials, and short films of his own. When I met him, he was gearing up to do this first feature. I’ve met many people in that camp who are going from short-form storytelling to long-form storytelling. He was very confident, ambitious, and certain of his abilities.

He’s very good at ensembles in a way that I am not. He talked me through how the knife salesman character would talk to these different characters as if they were real. He wasn’t talking about [Richard Brake’s bank robber character] Beau as if it was Richard. He would say, “Beau is this person who is dangerous.” I saw that as so seasoned and sophisticated, and I just bought into it. He’s very susceptible and very hypnotic. He’s like that hypnotist kid from “Cure.” After he had written that letter to me, he came to my backyard, and we talked about “South Park” for four hours. Then we had coffee and discussed the script and how it would move. I was going to try and make it work with my schedule … I thought I couldn’t, but at the very last minute, I could.

You talk about allure and hypnosis. One striking part about the rich characters is that we don’t get a lot of backstories, but we also know that they’re not all who they seem. Did you craft any backstory for your character when you played him?

(Laughs) I did. A lot of that was handed to me by Francis. He had a backstory for people and then was showing off the tip of the iceberg to us. We wanted my character just to be the knife salesman… that was a creative decision from Francis. But there was a lot of backstory. There was a lot about my relationship with my daughter and what this money could mean for our lives together. Francis and I would have these conversations about it.

A lot of that was heavily thought out, and I was just very lucky to receive it. Most times, when you’re an actor, you come on to a project, and all you have is the script, and you just have to nail the lines. With this one, it was fun to have that in my mind as I was playing this character. We tried to make something very earnest, where my character is a coward but has good reason to be.

You have this great line delivery where you tell someone to hold up just for a second when you are threatening them and your gun isn’t working.

(Laughs) Who is going to listen to that? A gun goes off, and there’s nothing in it, and then I say, “Hold on, stay right there.” How could I think I’m still in charge here? It’s so funny.

It’s a joy to see you have to improv and figure out your way to being menacing.

Yeah, it feels like he’s a 7-year-old trying to hold them hostage. Communicating all of that was so important. The movie that got Francis involved in making movies was “Funny Games.” That movie traumatized me, but it’s so good. There were times on set when we were shooting, especially when Richard’s character held us hostage, and that whole sequence where he and Travis hold my and Jocelin’s character hostage … that’s “Funny Games.”

It’s this human patheticism to be forced to be humiliated and emasculated. Francis and I spoke that same language. He’s a cinephile first and foremost, so we were able to, in making of the film, have this shorthand of saying, “Okay, so this scene is going to be ‘Funny Games,’ but then we’re going to transition so you have to be an idiot in this scene, but then in this next scene you’ve got to be Jackie Chan.” The film is very fluid in its genre.

That fluidity is one of the things that stood out to me in your character. You’re asked to command the screen alone for a bit, and while you’re a character the audience has to latch on to, you can’t play the knife salesman straight. We have to be a little distrusting and eerie of him, the same way we feel about the whole ensemble. What’s it like to balance those emotions of having high-pitched fright but also weave in the rage and belligerence?

Francis and I both love Bong Joon-ho. We both love “Parasite.” We always say that if you don’t make jokes throughout your movies, your audiences will. Audiences are very media literate. If a film is too austere or self-serious, you’ve lost them. In reading the script, I brought a lot of what I do, which is slapstick and vaudeville.

It was just a thousand conversations with Francis. It’s all kind of this equation that you’re building with the crowd. Francis is very considerate of that, of winning the audience and making sure that they’re constantly interested and entertained on the rollercoaster, hence my character’s shifting personality. I’m a filmmaker myself and I was already thinking through some of these things so talking with him about that … it was a very fluid conversation rather than an overdirected one.

In a past interview, you talked how you like to humiliate and humanize authority figures. What draws you to playing these types of rageful men who are drunk on their own self-importance? You touched on this a bit with that “humiliate and humanize” quote.

“Thunder Road,” the short film, was my first real maiden voyage into actual short-form art making. It’s quite good because I humiliate myself on-screen while dressed as an authority figure, in this case, a police officer. I’m following the tradition of people celebrated for doing the jester stuff for many years. I like that. It feels subversive. Whenever I would introduce “The Beta Test” to audiences, I’d say “every time you laugh at one of these characters, an agent dies.” Everybody would laugh! It’s a funny joke, but also when you do laugh, it does subvert the status quo and power dynamics of who’s in charge. It makes the powerless feel powerful.

It’s a fun challenge to show off. There’s a moment in the script where Richard is holding Jocelin’s character, Charlotte, hostage. He brings her over to the booth where I’ve just been sitting at, and he points to the knives I’ve just been previously selling to Charlotte and asks “What’s in the box?” I say “cheap kitchen knives.” Just the word “cheap” there makes my entire job so pathetic. I’m honest there because I’m held at gunpoint. For my character, my whole life is a lie. That’s so fulfilling to watch when you watch somebody be made pathetic because it speaks to a larger part of all of us. We all know that our lives are a charade and house of cards and that we’re all on this leash of money. It speaks to a greater humanity, I think, by playing these characters.

I thought the film was also poking fun at the glorification of spiraling. In the film’s case, it leads to dead bodies.

Yeah, that’s the old ‘crime doesn’t pay’ adage. It’s true. That’s the Westerns: you try to have a good point and reason in life, and you end up getting shot in the ditch. What’s the point? What’s really valuable? Those are the types of questions you’re traditionally supposed to take from a Western.

I feel like the audience strangely wants the bad stuff to happen, and to see these moments that they’re watching be the most interesting moments in the character’s lives. I think that’s why we like watching Karen videos on airplanes; there’s this lust for the void and morbid curiosity, and with each audience member who says, “I’m smarter than that person. I’m more powerful than that person. What a fool they’re making of themselves,” there are others who go, “Yeah, I’ve been there.”

You have the pesky fly buzzing around, the bird featured on the film’s poster, and Faizon Love’s character, Vernon, who has a dog … I’m curious how you interpret the use of those three animals in the film.

(Laughs) The amount of sound design we had to do for that fly … I mean days of work to get the sound accurate in that scene. There’s a scene where the fly is supposed to land on me but it lands on Richard, so we had to go back. It was really fun.

With animals, you’re very lucky if they do what they’re supposed to do. The bird in the beginning and the end is a trained bird that took the trainer a month, maybe three weeks, to get it to do what we wanted. But Francis always wanted the animals in this film. He wanted the desert to have this consistent presence of wildlife as a reminder that these things will always be around and survive us.

The consistency of starting and ending with the bird for the film was a metaphor about how the planet sees us doing this stuff and is like, “What are you doing?” The kind, three-legged dog is so nice. I feel like that was all this metaphor for how these animals will outlive us. The planet will do fine without us, but if we keep acting this way, we won’t survive it.

I know that Francis was recently announced as the director of a new Evil Dead installment. I’d love to see you throw it down with some Deadites. I could see this film being a stealth prequel to a new Evil Dead.

(Laughs) Oh my God. Can you imagine?

What are you most excited for him to bring to the franchise?

I grew up watching “Evil Dead.” “Army of Darkness” is my favorite. He’s the biggest fan of that franchise. We talked a little bit about it. We’ve talked about what he’s trying to do and what he’s hoping to do. It’s a difficult task. It’s a very beloved franchise, and you never want to fuck it up. In talking with David Gordon Green about 2018’s “Halloween,” it really plagued him. He was nervous that people would say, “Oh, another reboot that’s ruining the franchise.”

He had to learn so much about everything. He had to go through original manuscripts and absolutely everything to educate himself so that he wasn’t missing anything and could speak fluently about the franchise. That’s what Francis is doing now. With the help of Sam Raimi and Bruce Campbell, Francis is really trying to make something that is true to the core of “Evil Dead” while also being wild and new, which is what those two guys were doing from the beginning.