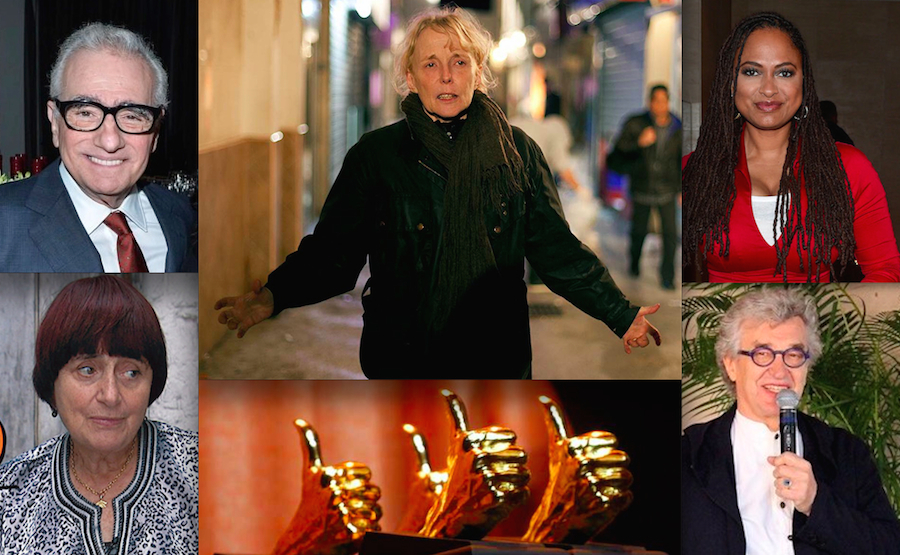

I AM PLEASED TO ANNOUNCE THAT RENOWNED FILM DIRECTOR CLAIRE DENIS will be honored at our annual Ebert Tribute Luncheon at the wonderful Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) on Monday, September 10th. I will be joining TIFF’s Artistic Director, Cameron Bailey, in hosting the event for Denis, a filmmaker my husband greatly admired. Her latest film, the sci-fi drama “High Life” starring Robert Pattinson and Juliette Binoche, is set to premiere at the festival.

The director’s 1988 directorial feature debut, “Chocolat,” received four stars from Roger, who said it evoked Africa better than any other film he had ever seen. “It knows how quiet the land can be, so that thoughts can almost be heard—and how patient, so that every mistake is paid for sooner or later,” Roger wrote, “The film is set in a French colony in West Africa in the days when colonialism was already doomed, but no one realized it yet. […] It is a movie about the rules and conventions of a racist society and how two intelligent adults, one black, one white, use their mutual sexual attraction as a battleground on which, very subtly, to taunt each other. The woman of course has the power; all of French colonial society stands behind her. But the man has the moral authority, as he demonstrates in the movie’s most important scene, which is wordless, brief, and final.” Roger hailed “Chocolat” as one of the year’s best films, praising its adult sensibility in how it suggests the sexual chemistry between characters who barely touch each other. “It is a deliberately beautiful film—many of the frames create breathtaking compositions—but it is not a travelogue and it is not a love story,” he wrote. “It is about how racism can prevent two people from looking each other straight in the eyes, and how they punish each other for the pain that causes them.”

Chocolat will also be screened at TIFF.

A decade later, Roger favorably reviewed Denis’ 1996 film, “Nanette et Boni,” describing its portrait of the titular siblings as a more delicate work from the “gifted” French director. He noted how the filmmaker tells the story of her characters “as if we already knew it. There are throwaway details, casual asides, events that are implied rather than shown. This creates a paradoxical feeling: We don’t know as much, for sure, as we would in a conventional film, but we somehow feel more familiar with characters because of her approach.” He once again admired Denis’ ability to saturate her film with sensuality that never turns explicit. “One of the most extended sex scenes involves Boni kneading pizza dough; what he does to the dough he does, in his imagination, to the baker’s wife, and that is going to be one happy pizza,” wrote Roger.

The late 2000’s proved to be an especially triumphant period for Denis, who released two of her most acclaimed pictures, the first being 2008’s “35 Shots of Rum,” a film that also earned four stars from Roger. “What matters is not the scope of a story, it’s the depth,” he wrote. “Part of the pleasure in Denis’ film is working out how these people are involved with the others. Two couples live across a hallway from each other in the same Paris apartment building. Neither couple is ‘together.’ Gabrielle and Noe have the vibes of roommates, but the way Lionel and Josephine obviously love each other, it’s a small shock when she calls him ‘Papa.'” A pivotal shift occurs during a dance scene where Denis tells us all we need to know not with plot points but with the character’s eyes, a key example according to Roger of what movies are for. “You can live in a movie like this,” he wrote. “It doesn’t lecture you. These people are getting on with their lives, and Denis observes them with tact. She’s not intruding, she’s discovering. We sense there’s not a conventional plot, and that frees us from our interior movie-going clock. We flow with them.”

Isabelle Huppert headlined Denis’s next film released the following year, 2009’s “White Material,” a film Roger dubbed “beautiful” and “puzzling” in his three-and-a-half star review. He reflected that the film expands on certain themes that were prevalent in the director’s work from the beginning. “Denis was born and raised in French Colonial Africa, and is drawn to Africa as a subject,” he noted. “Her first film, the great ‘Chocolat,’ was set there, and also starred the formidable Isaach De Bankole. Both it and this film draw from The Grass Is Singing, Doris Lessing’s first novel, the idea of a woman more capable than her husband on an African farm. Denis’ 2009 film, ‘35 Shots of Rum’ dealt with Africans in France. She doesn’t sentimentalize Africa nor attempt to make a political statement. She knows it well and hopes to show it as she knows it.” In “White Material,” Huppert plays a French woman who refuses to evacuate her farm in Africa, despite warnings of impending doom. “The enigmatic quality of Huppert’s performance draws us in,” Roger wrote. “She will never leave, and we think she will probably die, but she seems oblivious to her risk. There is an early scene where she runs in her flimsy dress to catch a bus and finds there are no seats. So she grabs onto the ladder leading to the roof. The bus is like Africa. It’s filled with Africans, we’re not sure where it’s going, and she’s hanging on.”

Last year, our critic Glenn Kenny awarded four stars to Denis’ romantic comedy, “Let the Sunshine In,” which won the SACD Prize at Director’s Fortnight in Cannes. Juliette Binoche stars as a divorced Parisian artist looking for love, and Kenny observed that the film’s opening sex scene had the “touch of a cinematic master” in how the characters were framed in compositions emphasizing “the space between their faces as much if not more than their faces.” Kenny admired how Denis avoided the simplicity of making a film about a smart woman’s bad decisions. “The director has treated a pretty wide variety of topics over the course of her long and wonderful career,” he wrote. “Female desire, as it happens, is not one she’s looked into often. 2002’s ‘Friday Night’ was the last time she took it on quite so directly. In that film, a young woman on the verge of entering a permanent union found herself in circumstances that allowed her a brief escape that could also have been an epiphany.”

“In this film, Isabelle, as beautiful and smart as she is, feels herself constricted by forces she can’t even confront,” Kenny continues. “Is it the most appropriate thing for her, at her age, to live, as she puts it, a ‘life without desire?’ Clearly no. But the film does confront the fact that particularly for women, pursuing desire in middle age is a fraught path. To add a twist to this demonstration, Denis breaks it off late in the movie, and jumps briefly into someone else’s storyline, someone who had been a stranger up to this point. Then the filmmaker wraps it up in a final shot that’s both cerebral, whimsical and wry in its wisdom. The film’s confidence comes in part from the acceptance of the things that can’t be known.”