There’s an offhand cockiness to the characters in “Nenette et Boni” that reminded me of “Jules and Jim” and the other early Truffaut films where characters acted tough but were really emotional pushovers. Boni, a dreamy 19-year-old kid in Marseilles, shoots his pellet gun at a neighbor’s cat, but has untapped reserves of romanticism and tenderness. It’s Nenette, his 15-year-old sister, who’s been tempered by life.

Claire Denis, the gifted French director, tells their story as if we already knew it. There are throwaway details, casual asides, events that are implied rather than shown. This creates a paradoxical feeling: We don’t know as much, for sure, as we would in a conventional film, but we somehow feel more familiar with characters because of her approach.

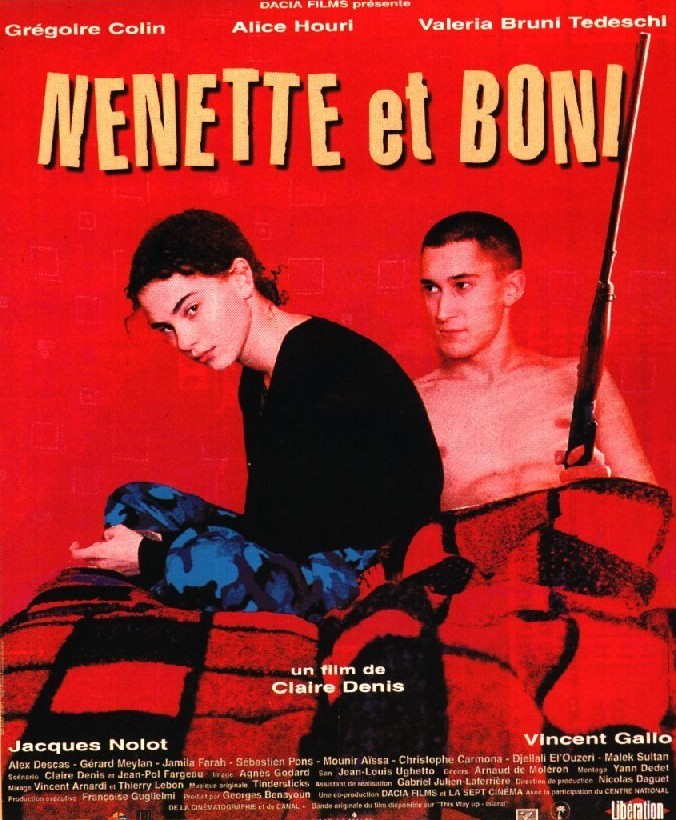

Nenette and Boni are the survivors of an apparently ugly divorce. After the breakup, Nenette (Alice Houri) lived with her father, and Boni (Gregoire Colin) with his mother. Now Boni lives alone, and one day Nenette turns up, seven months pregnant. She doesn’t want the baby, but it’s too late for an abortion, and so she accepts approaching motherhood with a grim indifference. Boni, on the other hand, is thrilled; he cares tenderly for the young mother-to-be, and dotes on every detail of the pregnancy.

They form, if you will, a couple. Not one based on incestuous feelings, but on mutual need and weakness: Boni provides what emotional hope Nenette lacks, and her pregnancy adds a focus and purpose to his own life. It is something real. And reality is what he’s been lacking in a love life based largely on his inflamed fantasies about the plump wife (Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi) of the local baker (Vincent Gallo, playing an American in France).

“Nenette et Boni” is one of those movies that is saturated with sensuality but not with explicit detail. One of the most extended sex scenes involves Boni kneading pizza dough; what he does to the dough he does, in his imagination, to the baker’s wife, and that is going to be one happy pizza.

Boni is sort of a moody kid, who keeps a pet rabbit and is apt to fall thunderstruck into long reveries of speculation or desire. The approaching childbirth is a reality check for him; we sense it will be one of the positive, defining moments of his life. About Nenette we aren’t so optimistic. There are vague, alarming possibilities about the father of her child–the film acts like a family member that knows more than it says–and it may be years before Nenette recovers her emotional health.

Claire Denis, born in French Africa, is a director who seems drawn to stories about characters who want to build families out of unconventional elements. I have never forgotten the haunting emotional need in her first film, “Chocolat” (1989), about a mother and daughter living in an isolated African outpost, the father absent, and finding themselves drawn to an African foreman whose ability and stability offered reassurance.

With “Nenette et Boni,” she makes a more delicate film. She feels affection for the characters, especially Boni, and is very familiar with them. Maybe that’s why she feels free to tell the story so indirectly. This isn’t a chronicle of events in two lives, told one after another. It’s more like an affectionate fond chat. “And Boni? How is he?” you imagine the audience asking her, just before the movie begins. And Denis replying, “Oh, you know that Boni … .”