Isabelle Huppert, small and slender, embodies the strength of a fighter. In so many films, she is an indomitable force, yet you can’t see how she does it. She rarely acts broadly. The ferocity lives within. Sometimes she is mysteriously impassive; we see what she’s determined to do, but she sends no signals with voice or eyes to explain it. There is a lack of concern about our opinion; she will do it, no matter what we think her reasons are.

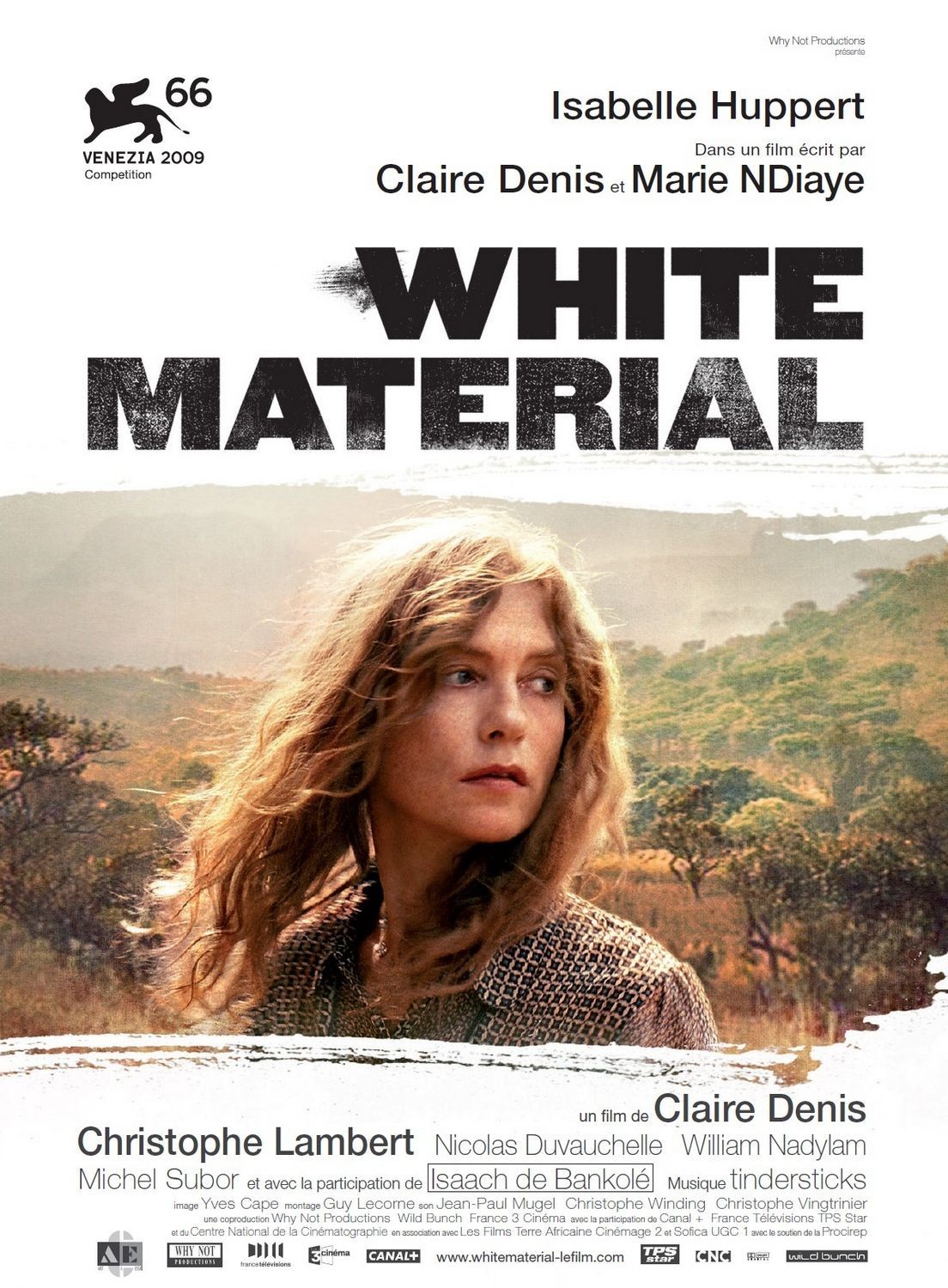

In Claire Denis‘ “White Material,” she plays Maria Vial, a French woman running a coffee plantation in an unnamed African country. The land has fallen into war, both against the colonialists and among the insurgents. In an opening scene, a helicopter hovers above Maria and French soldiers advise her to evacuate quickly. This she has no intention of doing. As it becomes clear that her life is in danger, she only grows more opaque. Huppert’s approach is valuable here, because any attempt at a rational explanation would seem illogical. I believe her attachment to the land has essentially driven her mad.

This isn’t even her farm. It was owned by her former father-in-law and run by her ex-husband (Christopher Lambert). Now she is in day-to-day charge and moves with confidence. The way she dresses makes a statement: She likes simple sandals and thin print sundresses that make her seem more at home than durable clothing would. She doesn’t even much like hats or sunglasses. She runs through fields like a child. She drives a truck, runs errands, goes into town to hire substitute labor when her workers walk away in fear of the war. There’s a scene where she all but tries to physically restrain departing workers.

They try to be reasonable with her. Yes, it will be a good crop of coffee beans, but there will probably be no way to get it to market. Anarchy has taken over the land. Child soldiers with rifles march around, makeshift army stripes on their shirts, seeking “The Boxer” (Isaach De Bankole), a onetime prizefighter and now the legendary, if hardly seen, leader of the rebellion. When Maria is held at gunpoint, she boldly tells the young gunmen that she knows them and their families. Her danger doesn’t seem real to her. There is no overt black-white racial tension in the film; the characters all behave as the situation would suggest.

Claire Denis, a major French director, was born and raised in French Colonial Africa, and is drawn to Africa as a subject; her first film, the great “Chocolat” (1988), was set there, and also starred the formidable Isaach De Bankole. Both it and this film draw from The Grass Is Singing, Doris Lessing’s first novel, the idea of a woman more capable than her husband on an African farm. Denis’ 2009 film “35 Shots of Rum” dealt with Africans in France. She doesn’t sentimentalize Africa nor attempt to make a political statement. She knows it well and hopes to show it as she knows it. Huppert’s impassivity perhaps suits her; the character never expresses an abstract idea about the farm or Africa, and the nearest she comes to explaining why she won’t leave is asking, “How could I show courage in France?” No one asks her what that means.

We meet the ex-husband and his father, but the other major figure in the film is her son, Manuel (Nicolas Duvauchelle). This boy, in his late teens, seems prepared to spend all of his life in his room. While his mother manages the farm, he projects indolence and total indifference. He cares not about her, the farm or anything. Events cause him to undergo a scary transformation, but it’s not one we were expecting. He doesn’t move in a conventional narrative direction, but laterally, driven by inner turmoil.

This is a beautiful, puzzling film. The enigmatic quality of Huppert’s performance draws us in. She will never leave, and we think she will probably die, but she seems oblivious to her risk. There is an early scene where she runs in her flimsy dress to catch a bus and finds there are no seats. So she grabs onto the ladder leading to the roof. The bus is like Africa. It’s filled with Africans, we’re not sure where it’s going, and she’s hanging on.