It’s hard to know where to begin with “The Life of Chuck.” Anything you could say about it would rob new viewers of the specialness that comes from going in completely fresh. Suffice to say that it’s suitable for all audiences and that it’s a great example of popular cinema’s ability to speak to the life experiences of a large cross-section of viewers without dumbing anything down. It straddles the edges of both greeting-card oversimplifications and sentimentality, but does not cross over, leaving the audience to discuss what, exactly, the takeaway might be.

An adaptation of the same-titled short story by Stephen King, this feature from writer-director and King adaptation specialist Mike Flanagan (“Doctor Sleep“) is broken into three…well, “acts” doesn’t feel right, because this isn’t a conventional drama; so let’s say “movements,” the word that describes the section of a symphony or other classical music piece. This is a musical movie, not just because it features musical numbers. It weaves its spell not merely by what it does, but how it moves, and what it chooses to say or not say, and when it decides to proceed to the next scene.

The movie is a non-chronological look at the life of an accountant named Chuck Krantz, played as an adult by Tom Hiddleston and in younger incarnations by juvenile performers. The first movement is set in a future where civilization, as we’ve always known it, appears to be falling apart, beginning with Internet failure and progressing from there to electric power and possibly even existence. The main characters are two public school teachers, Marty Anderson (Chiwetel Ejiofor) and Felicia Gordon (Karen Gillan), who were once married. They come together again when they talk on the phone as crisis friends, and Marty impulsively decides to visit her. There’s a long, lovely scene en route to the reunification in which Marty has a wide-ranging conversation with his old friend Sam Yarborough (Carl Lumbly), the owner of a beloved local funeral home, and who (we later learn) happens to be the man who buried people who were important to Chuck.

News reports keep intruding or adding to scenes. Technologies and services that we take for granted are no longer guaranteed. Online access ends early in the story. Phones are next. There is an earthquake in California that tears away part of the state and dumps it into the sea. More disasters are coming. The environment is collapsing—or maybe you could read it as rebelling. And images of Chuck start appearing everywhere. Who is this man? A billboard says that everyone is supposed to thank him for 39 wonderful years. What does this mean? How will it relate to the rest of the movie?

All of the film’s movements could be self-contained short movies, but the middle one, which concentrates on a single moment, is the neatest. The adult Chuck passes a street drummer (Taylor Gordon) and spontaneously breaks into an improvised dance routine, then beckons a recently-dumped onlooker, Janice Halliday (Annalise Basso), to join him. There’s true chemistry between them. What will they make of it?

The entire movie is, you retrospectively realize, filled with moments in which characters make flash decisions that lead to great satisfaction or great sadness or something else. It’s a sideways route to get into the idea that every moment in life counts for something, and that, by extension, you have to make every moment count, or at least be present, because you never know when Death is going to punch your ticket. Don’t worry, though: this isn’t the kind of movie where people’s lives are picked apart like equations until they locate the instant where things went wrong, or right. It’s more mysterious than that. Flanagan (who also edited) allows you to bring a lot of yourself to the work, which accounts for why it feels so warm and embracing overall, despite its formal gamesmanship.

The denouement of Chuck and Janice’s dance becomes more powerful once you’ve absorbed the final act, which covers Chuck’s childhood and adolescence. A moment that was teased in a very brief, wordless flashback in the middle movement is filled out at length when we meet Chuck’s grandparents, played by Mark Hamill as his grandfather (a strong and moral man whose advice is not the best) and Mia Sara as his grandmother, who loves to dance. (Sara is beguiling; her short salt-and-pepper haircut, bright smile, and big, wise eyes momentarily made me wonder if she was a great French actress whose name I should’ve known.) Life choices are made here, too. But the much wider time frame covered in this final movement creates a slipstream effect that’s a bit like remembering one’s youth as an adult. Pieces of time that seemed to take forever when you were a kid pass in the blink of an eye when you get older.

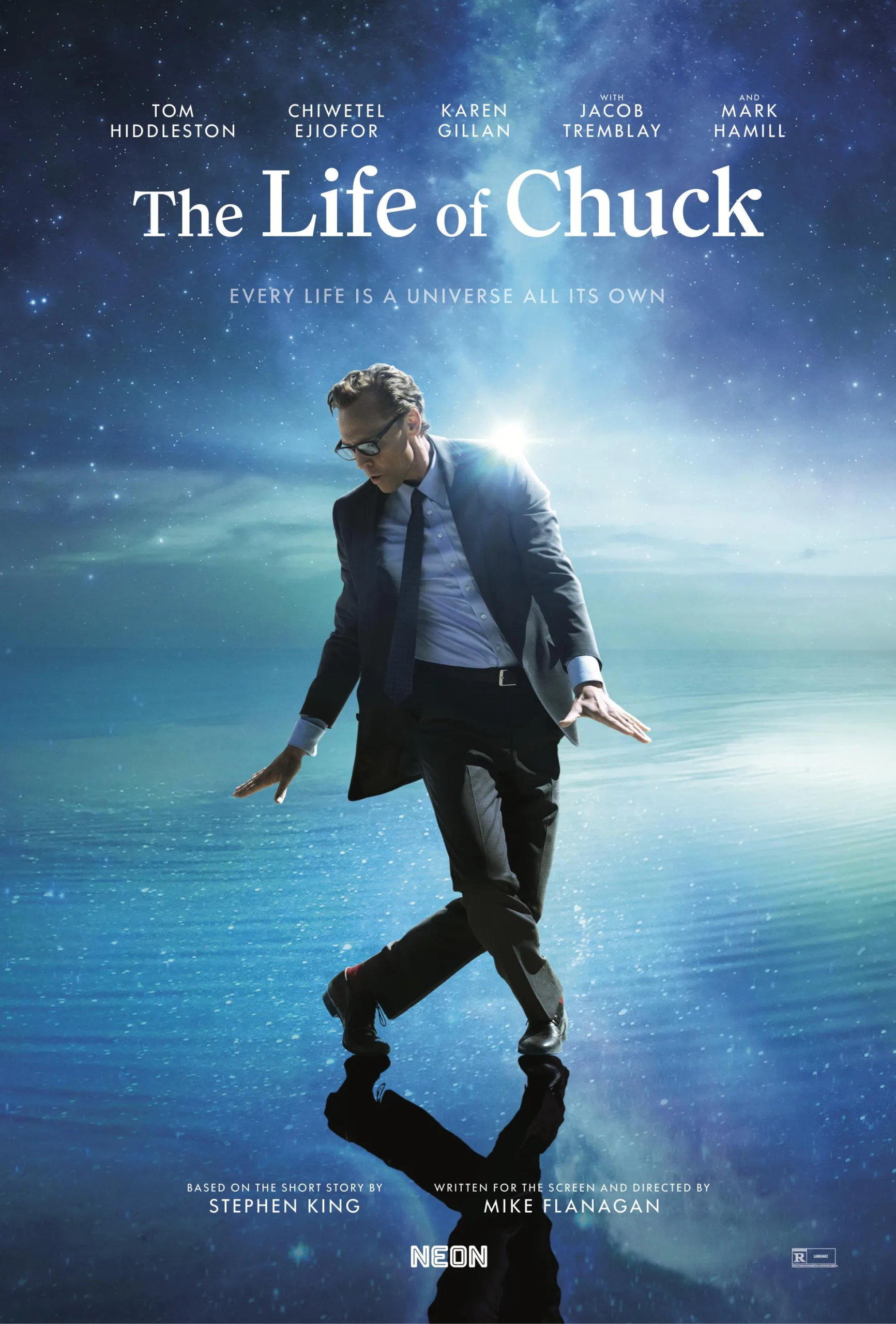

Every performer makes a strong impression, including those who get just one scene. One is Matthew Lillard, deeply moving in the first section, where his character, an ordinary man, unloads on Marty, bringing himself to tears. Ejiofor invests Marty with an understated authority and empathy, as does the sensitive and alert Gillan, who is shaping up to be one of those actresses that you’re always glad to see. Hiddleston is on the movie poster (dancing!) and serves as the movie’s avatar, in a way, although he’s only really in the middle section. But he brings a dignified pathos to his appearance that’s all the more powerful for being understated.

There are a lot of literary and cinematic antecedents here, from “A Christmas Carol” and “It’s a Wonderful Life” to “Amélie” and the brilliant Belgian movie “Totos les Hero” (worth seeking out if you haven’t already seen it) and another wish-it-was-better-known biography, “32 Short Films About Glenn Gould.” But ultimately, this movie is very much its own thing.

“The Life of Chuck” has been widely described as “science fiction,” including by its own distributor, Neon. However, I question whether that’s entirely accurate, just as I do for some Kurt Vonnegut novels—most notably Slaughterhouse Five. Both move through the life of their hero non-chronologically and contain science fiction elements but could just as easily be understood as a glimpse inside the scrambled consciousness of a man looking back on his life. Let’s say that in “The Life of Chuck,” you can go with either interpretation or some other one and be on solid ground. You can take a lot of elements in this movie in more than one way, really. That’s a compliment to the filmmakers. A lot of movies barely have a point of view at all. This one is a prism in comparison. It gives viewers what David Lynch called “room to dream.”