By all

logic, Richard Lester deserves consideration as one of the key filmmakers to

emerge in the latter half of the 20th century. Over a career spanning 22

feature films, he has had a number of critical and commercial successes

(including one that won the top prize at Cannes), his unique directorial style—shifting effortlessly from classical elegance to formally

radical depending on the needs of the material—has

influenced any number of filmmakers over the years (one notable fan, Steven

Soderbergh, even collaborated with Lester on a book about his career, the

must-read “Getting Away With It”) and one of his films has gone on to

be enshrined as one of the all-time greats in the history of the medium. And

yet, for several reasons—the relatively low profile

that he kept as a filmmaker even at the apex of his career, the high profile of

the personalities that he worked with on many of his biggest hits, his

inability to be pigeonholed as a single entity (not even in terms of his

nationality—Lester’s name has threatened

to fade away in the minds of the movie-going public except as the guy who

directed the first two films featuring The Beatles.

Hoping to

reverse that trend and expose Lester’s wide-ranging filmography to a new

generation of moviegoers, the Film Society of Lincoln Center in New York has

put together “Richard Lester: The Running Jumping Pop Cinema

Iconoclast,” a career retrospective running August 7-13 that will

encompass 15 of his films—all but three of them being

presented in 35mm and one actually serving as its long, long-delayed debut U.S.

theatrical presentation—that illustrate how he was

able to work in any number of genres with a wit and style that was uniquely his

own. Although not a complete retrospective—some may question the absence

of his first feature, the 1962 youth-oriented musical “It’s Trad,

Dad” or his superhero epics “Superman II” (1981) and

“Superman III” (1983)—the films programmed here are

all significant works and any true movie fan attending the program will be able

to reacquaint themselves with some old favorites and perhaps get a chance to expose

themselves to a couple that they somehow missed over the years.

Born in

1932, Lester, a child prodigy who entered the University of Pennsylvania at the

age of 15, originally looked towards a career in clinical psychology but soon

shifted his focus when he went to work for a local television station and rose

through the ranks until he became a director. Believing that there were more

opportunities in his newly-chosen career path in England than in the U.S., he

transplanted to London and soon became a power in the industry, even becoming

the star of the variety series “The Dick Lester Show.” The show

didn’t last too long but the touches of surreal comedy on display attracted the

attention of no less a figure than Peter Sellers, who hired Lester to direct a

couple of “Goon Show” reunion specials and, more significantly, the

groundbreaking 1959 short film “The Running, Jumping & Standing Still

Film,” a silent comedy homage that earned an Oscar nomination for

Live-Action Short as well as a chance for Lester to move into features with

“It’s Trad, Dad!” After the success of that film, Lester was hired to

direct “Mouse on the Moon,” a sequel to the 1959 hit “The Mouse

That Roared” that saw the tiny country of Grand Fenwick stumble into the

space race when their chief export, a dreadful wine that keeps exploding in the

bottle, is actually a potent rocket fuel. Although not nearly as entertaining

as the original, in no small part because of the absence of Sellers from the

cast (though he was instrumental in getting Lester hired for the job), it did

relatively well at the box office and it led to that film’s producer, Walter

Shenson, to ask Lester to direct his latest project, a film designed around a

currently popular music group that had to be produced and distributed within a

few months—before fans moved on to the

next big thing.

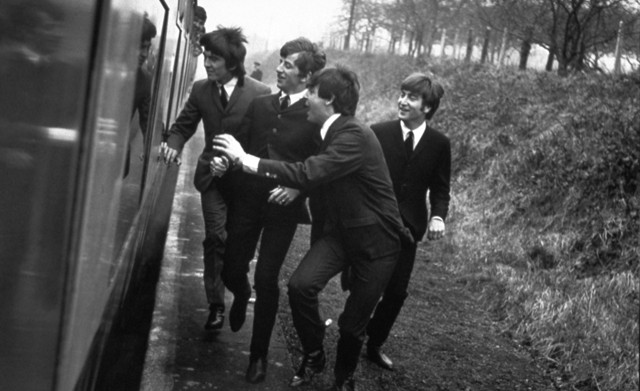

The

group, of course, was The Beatles, the film in question was, of course, “A

Hard Day’s Night” (1964) and Lester’s lightly exaggerated look at a day in

the life of the newly-minted stars proved to be as groundbreaking and as

sheerly entertaining as the music that it was designed to highlight. As I am

assuming that anyone who has read this far into this piece has doubtlessly seen

the film any number of times, I am going to assume that a long explanation of

what makes it so special, even today, is unnecessary. Instead, I would like to

give a little more attention to “Help,” the 1965 reunion between

Lester and the group, whose popularity had only grown in the interim. The film,

a bit of surreal silliness involving the boys being pursued around the world by

members of a cult after Ringo gets their sacred sacrificial ring stuck on his

finger, has never had the best reputation among fans and critics alike, and

watching a story about a group of murderous fanatics trying to kill one of the

Beatles admittedly plays very differently now than it did a half-century ago.

That said, I must confess that, while acknowledging every one of the earlier

film’s achievements, I actually prefer “Help” to its predecessor.

From the first time I saw it as a young child, I fell in love with its

cheerfully cartoonish nature and offbeat knockabout comedy beats (such as a

tiger that can only be quelled by singing Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”

and the ending dedication to Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine)

and the nuttiness Lester brought to the proceedings remains as infectious today

as it did back then.

In

between the two Beatles projects, Lester made “The Knack…and How to Get

It,” an adaptation of Ann Jellicoe’s 1962 novel about the then-ascendant

youth culture in London that focused on the competition that develops between

three young man—shy schoolteacher Colin

(Michael Crawford), womanizing Tolen (Ray Brooks) and the artistic Tom (Donal

Donnelly)—to win the favors of the newly

arrived and freshly liberated Nancy (Rita Tushingham). A relatively

straightforward proposition on stage, Lester made stylistic changes to the

material that pushed it even beyond what he accomplished in “A Hard Day’s

Night,” including off-beat editing patterns, characters directly

addressing the camera and a Greek chorus of older people commenting on the

misadventures of the younger generation. When it was completed, Lester’s bold formal

experiment did not win many fans at first—Jellicoe reportedly hated what

was done to her play and executives at United Artists, who had such a hit with

“A Hard Day's Night,” dismissed it as well and considered dumping it

as the bottom half of double bills. Unexpectedly, it was entered into

competition at that year’s Cannes Film Festival and wound up winning the

coveted Palme d’Or in the process, though it did not make much of a commercial

impact in America. Today, the film is a little dated in parts but it still has

an energy to it that is undeniable, and many of the things that it has to say

about young male-female relationships are still painfully relevant today.

(Sharp-eyed viewers will notice that three of the most beautiful actresses to

ever set foot in front of a movie camera make their big-screen debuts here—Charlotte Rampling, Jacqueline Bisset and Jane Birkin.)

Despite

the critical and commercial accomplishments he had achieved to this point,

there was some rumbling in certain circles that Lester was the proverbial

emperor sans clothes and that there wasn’t much to his films once you took away

the surface flash and iconoclastic attitude. Whether these opinions reached

Lester at all is unknown, but his next couple of movies did find him stretching

outside of the comfort zone that he had established for himself with mixed

results. A 1966 feature version of the

Broadway hit “A Funny Thing Happened to Me on the Way to the Forum”

offered him the chance to step up to the big leagues but the results were

uneven—there were the nifty Stephen

Sondhem songs and comedy legend Buster Keaton in what would be his final screen

appearance but these good points were outweighed by a turbulent production (the

writer-producer was under the impression that he was going to be directing it

and when that didn’t pan out, he and Lester found themselves at loggerheads

regarding virtually everything about the production), a wildly over-the-top

performance by Zero Mostel as Pseudolous, the slave trying to help his young

master win the heart of the virginal courtesan next door in exchange for his

freedom, and the nagging sense that this was a property best appreciated on the

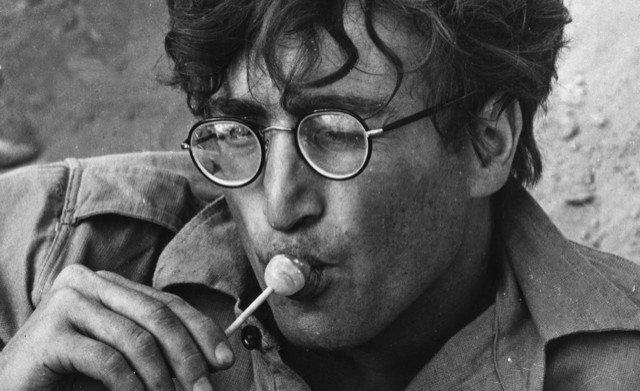

stage. The next year, he came up with “How I Won the War,” a WWII

satire about a group of soldiers sent behind enemy lines to build a cricket

pitch for a visiting dignitary. Lester ambitiously designed the film to be both

an anti-war statement and a protest against the jingoistic war movies that he

felt were equally insidious in how they formed pro-combat attitudes in

unsuspecting viewers. The result is an undeniably intriguing film, but one that

proved to be difficult for most viewers to embrace and when it is remembered

today, it is mostly because of the presence of John Lennon in an unassuming

supporting turn as one of the soldiers.

For his

next project, Lester took the bold step of returning to his home country for

the first time in fifteen years to shoot an adaptation of a novel about the

relationship that unexpectedly develops between a straight-laced doctor in the

throes of a divorce and an unhappily married free-spirit socialite that would

play out during the end days of the legendary Summer of Love in San Francisco.

The resulting film, “Petulia,” would prove to be Lester’s most deliberately

mature vision to date in the way that is observed both the relationship between

the two characters (expertly and heartbreakingly played by George C. Scott and

Julie Christie) and the relationship between Lester himself and the country

that he once called home but now had difficulty recognizing anymore. Released

during a particularly chaotic point in American history—it premiered a week after the assassination of Robert F.

Kennedy—“Petulia” was a

non-starter at the box-office and sharply divided critics between those who

found it a revelation and those who found it a sour and unpleasant mess. In

subsequent years, however, opinions of the film have shifted greatly and

“Petulia” is now generally considered to be one of the high-water

marks of Lester’s entire career and the first time that he allowed a genuine

emotional core to coexist with the cynical social satire. Even today, its final

images still retain enough power to inspire a tear or two in the eyes of even

the most jaded of moviegoers.

Although

“Petulia” would become his third under-performer at the box office in

a row, Lester still had a certain amount of clout in the movie industry and he

would invest virtually all of it in his next project, which would prove to be

the darkest, strangest and most formally daring work of his career. This was

“The Bed Sitting Room,” a deeply surreal and blackly comic adaptation

of the Spike Milligan/John Antrobus play set a few years after a nuclear war

(lasting 2 minutes and 28 seconds) has devastated most of the world and which

follows a handful of survivors as they wander through the wreckage of what was

once London. A young woman (Rita Tushingham) is 17 months pregnant and lives on

the still-functioning Circle Line train with her parents. The BBC is reduced to

one man who goes door-to-door to read the news from behind the screens of

hollowed-out televisions. A lord (Sir Ralph Richardson) is convinced that he is

about to mutate into a bed-sitting room. The National Health Service has been

reduced to one male nurse played by Marty Feldman and the entire police force

consists of two officers (Dudley Moore and Peter Cook) who do nothing but

advise anyone they encounter to “keep moving” so as to prevent them

from being targets of a future war. The monarchy, by the way, is now in the

hands of Mrs. Ethel Shroake, a former maid of the Queen’s who is the closest in

succession to the throne.

Watching

“The Bed Sitting Room” today, it seem incredible that such a thing

could have ever made it through the production process. The comedy is both

pitch-black and of a decidedly British nature, and the final third veers into

outright tragedy before a conclusion that tries to find a small glimmer of hope

amidst all the chaos and horror and astonishingly manages to pull it off while

staying true to the material. Needless to say, when the studio heads at United

Artists took a look at it, they were appalled at what they saw (to be fair, it

seems that the famously hands-off organization was still under the impression

that Lester was doing a musical version of Joe Orton’s “Up Against

It” starring Mick Jagger, the project he had been working on before

shifting his focus after that one fell through) and shelved it for more than a

year. When it did finally appear in 1970, it was such a bomb with critics and

audiences alike that not only did it fail to make a cent at the box office, it

derailed Lester’s directorial career entirely for the next few years.

Although

it would take a few years for him to get back into the filmmaking game in the

Seventies, his eventual return would yield a variety of intriguing films that

found Lester dabbling in a number of unusual genres. His return from the

wilderness began when the father/son producing team of Alexander and Ilya

Salkind hired him to direct an epic production of Alexandre Dumas’ “The

Three Musketeers,” a project that he had once contemplated as a vehicle

for the Beatles. Instead, Lester brought together an all-star cast, including

Michael York, Oliver Reed, Richard Chamberlain, Faye Dunaway, Christopher Lee,

Raquel Welch, Spike Milligan and Charlton Heston and punched up the story with

a lot of humor and elaborate swordplay. Although Lester conceived it to be one

long film, the Salkinds decided to split it into two parts—“The Three Musketeers” (1973) and “The Four

Musketeers” (1974)—and while this move enraged

the actors (who were now making two movies for the price of one), both parts

proved to be hugely popular with critics and audiences alike and remain

arguably the definitive screen adaptation of the story.

Between

the releases of the two Musketeers films, Lester managed to squeeze out another

film when he was hired at the last second to take over the production of

“Juggernaut,” a suspense thriller about a bomb disposal team (led by

Richard Harris) who are sent off to disarm a number of explosive devices that

have been hidden throughout an ocean liner in the middle of the North Atlantic

sea while British police back on shore desperately try to uncover the identity

of “Juggernaut,” the person who vows to blow up the ship unless they

are paid $1.5 million dollars. (The story was inspired by a real-life bomb hoax

involving the QE2 in 1972.) An uncommonly serious-minded effort for Lester

(though it does have a couple of moments of humor), the film is as tense and

gripping as they come as Lester manages to keep the white knuckle material

going for nearly two solid hours, aided in no small part by an excellent cast

that also included the likes of Omar Sharif, Anthony Hopkins, Shirley Knight,

Ian Holm and David Hemmings.

For his

next film, Lester returned to a once-shelved plan to bring the adventures of

Sir Harry Paget Flashman, the lying, cheating, thieving and cowardly rat at the

center of a series of comedic adventure novels by George MacDonald Fraser, to

the big screen. Based on the second book in the series, “Royal Flash”

(1975) followed Flashman (Malcolm McDowell) as he is forced by Otto von

Bismarck (Oliver Reed) to impersonate a Danish prince about to marry a German

princess (Britt Ekland) as part of his diabolcal plan to unify Germany under

his rule. The film is funny enough in parts and McDowell is pretty much perfect

as Flashman but the plot is little more than a rehash of “The Prisoner of

Zenda” and the blend of strange humor and action did not jell as well as

it did with the Musketeers movies and critics and viewers alike were left cold

by it.

A far

more successful revisionary look at a familiar narrative, Lester’s next film,

“Robin and Marian” (1976) offered moviegoers the sight of a now-aging

Robin Hood (Sean Connery) returning from the Crusades at last to woo Maid

Marian (Audrey Hepburn), who has become an abbess in the interim, while

rescuing her from the depravations of the Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw).

While the film may lack the derring-do of previous screen incarnations of the

myth, “Robin and Marian” is nevertheless a glorious work in which the

perfectly cast Connery (in arguably his best performance of the Seventies) and

Hepburn (making her first screen appearance in 8 years) demonstrate incredible

screen chemistry and Lester dials down the comedy and visual flash so as to let

it shine through even brighter. In the long history of Robin Hood films, this

one probably ranks behind only the Errol Flynn classic “The Adventures of

Robin Hood” (1938), and there are times when I am convinced that it beats

out even that one.

The rest

of the decade saw Lester tackling a number of unfamiliar genres with mixed

results. “The Ritz” (1976) was an adaptation of the Terrence McNally

play that is set entirely within the confines of a gay bathhouse in Manhattan

where a straight businessman (Jack Weston) has gone to hide out from his

mobster brother-in-law (Jerry Stiller) with the usual wacky results. This

attempt to do an updated version of the classic screwball comedies of old must have

seemed promising on the page, but the results are a little too forced at times

for their own good and the laughs never really build, though Lester does get

good performances from the cast.

“Butch and Sundance: The Early

Years” (1979) remains one of the oddest entries in his filmography—not only was he entering the unfamiliar realm of the

Western but he was doing it with a prequel to one of the most beloved films of

its time and one which derived much of its power from star casting that simply

wasn’t possible this time around. The end result is not quite as bad as its

reputation suggests, but the combination of a dramatically limited narrative

and two stars (Tom Berenger and William Katt) who were simply not Paul Newman

and Robert Redford helped to doom it. Far more interesting was “Cuba”

(1979), a romantic melodrama set against the fall of the Batista government and

the rise of Fidel Castro that starred Sean Connery as an ex-soldier hired to

train Batista’s men to fend off Castro’s army, a mission that he concedes from

the start is doomed to fail. While there, he runs into an old flame (Brooke

Adams) who is now married to a sleazy plantation owner and their affair

rekindles amidst the chaos of the ever-growing revolution. The parallels to

“Casablanca” are obvious, but Lester finds a way to make the material

seem fresh (something that Sydney Pollack was unable to do a decade later with

the similar “Havana”) and the romance between Connery and Adams

generates some heat. Like many of Lester’s best works, this floundered in its

original release but is ripe for rediscovery.

Lester

rebounded commercially fairly quickly when his job serving as an uncredited

producer on “Superman” (a ploy by the Salkinds to goad director

Richard Donner, with whom they were feuding, to quit) led to his being asked to

direct “Superman II,” the result of the Salkinds pulling another “Three

Musketeers” by trying to do two movies at once. Although the production

was rocky and Lester was required to utilize footage that Donner had shot

(including all the stuff with Gene Hackman), the resulting film was a hugely

entertaining work that saw Lester shift the tone from the straightforward epic

feel of its predecessor to some more overtly comic book in nature—ironic since Lester claimed to have never read and comics

before and to have had only the vaguest understanding of what Superman was in

the first place.

“Superman

III” was also a Lester film, and while it’s a little

better than its reputation, the picture is undone by a lame villain (Robert Vaughn as a

standard megalomaniacal millionaire who belongs in an episode of

“Batman“) and the need to shoehorn Richard Pryor, then at the height

of his box-off popularity, into a plot that simply did not need him.

“Finders Keepers” (1984) was another stab at screwball farce, involving

a fugitive (Michael O'Keefe) who boards a train with a stolen coffin that

contains millions of dollars inside. Despite a decent cast (that also includes

Beverly D'Angelo, David Wayne, Pamela Stephenson and a then-unknown Jim

Carrey), it just never pulled together and is probably the most utterly

indistinct film that Lester ever made.

After a

five-year hiatus from filmmaking, Lester returned to the site of one of his

greatest former glories when he took on “The Return of the

Musketeers” (1989), an adaptation of Dumas’s “Twenty Years

After” that reunited several cast members from the original films

(including Michael York, Oliver Reed, Richard Chamberlain, Christopher Lee and

Roy Kinnear) along with newcomers C. Thomas Howell (as the son of Athos) and

Kim Cattrall (as the vengeance-seeking daughter of Milady de Winter) for more

derring-do. During the production of the film, tragedy struck when Roy Kinnear,

who had worked with Lester several times in the past, was thrown from his horse

during the shooting of a scene and broke his pelvis. While being treated for

his injuries in a Spanish hospital, he had a heart attack and died. The

incident crushed Lester, and since he no longer felt confident of his ability

to protect his actors from harm, he essentially retired from filmmaking and

while he never made a formal announcement along those lines, the only thing

that he has directed since then was “Get Back” (1991), a film

chronicling Paul McCartney’s sold-out 1989 tour. To add insult to fatal injury,

“The Return of the Musketeers” failed to find distribution in the

U.S. and wound up making its debut on cable in 1991, making its showing at this

retrospective its unofficial and long-delayed U.S. theatrical premiere.

Richard

Lester has been a major force in the world of cinema over the last half-century.

The fact that he is not considered one of the great filmmakers of his time is

one of those sad flukes of cinema history that a retrospective like this will

hopefully help to rectify. He may be most famous as “The Man Who Framed

The Beatles,” as one biography described him, but as anyone who checks out

some of his other films will quickly realize, he was much more than that.

For more

details on “Richard Lester: The Running Jumping Pop Cinema

Iconoclast,” running August 7-13 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, go

to the official

site.