Richard Lester’s “Petulia” made me desperately unhappy, and yet I am unable to find a single thing wrong with it. I suppose that is high praise. It is the coldest, cruelest film I can remember, and one of the most intellectual.

By that I don’t mean it’s filled with philosophy, like Bergman, or with metaphysics, like “2001.” On the contrary, it’s filled with nothing at all. It is lifeless, heartless bloodless, the expression of Lester’s abstract thought about the American way of life. And it is terribly effective.

Most films come with emotions wrapped inside. We pick a movie according to the emotion we desire: a musical to be happy, a Western to be thrilled. “Petulia” doesn’t work this way. It provides no built-in emotional response at all. Instead, it glides perfectly across the screen, and the idea is for audience the audience to provide its own emotion by responding to it.

Off-hand, I can think of only two other films that worked this way: Antonioni’s “Eclipse” and Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad.” To one degree or another, both of these inspired impatience, confusion and irritation. Yet when they were analyzed, they turned out to contain nothing more than the components of everyday life. So what were we irritated at? The lives we lead?

I think so. We are living in an increasingly sanitary, air-conditioned, computerized, Saran-wrapped, Muzaked society. Supermarkets aren’t food stores anymore, but hypnotic temples of consumer spending. Public buildings are filled these days with half-audible hums (air conditioning) and buzzes (the lights). Elevators play “Whistle a Happy Tune” at you while you stare at the floor numbers over the door. People unconsciously elevate their manners to fit these clean new environments, nodding graciously to each other in the supermarket aisles as if they were actors in a commercial for living better electrically.

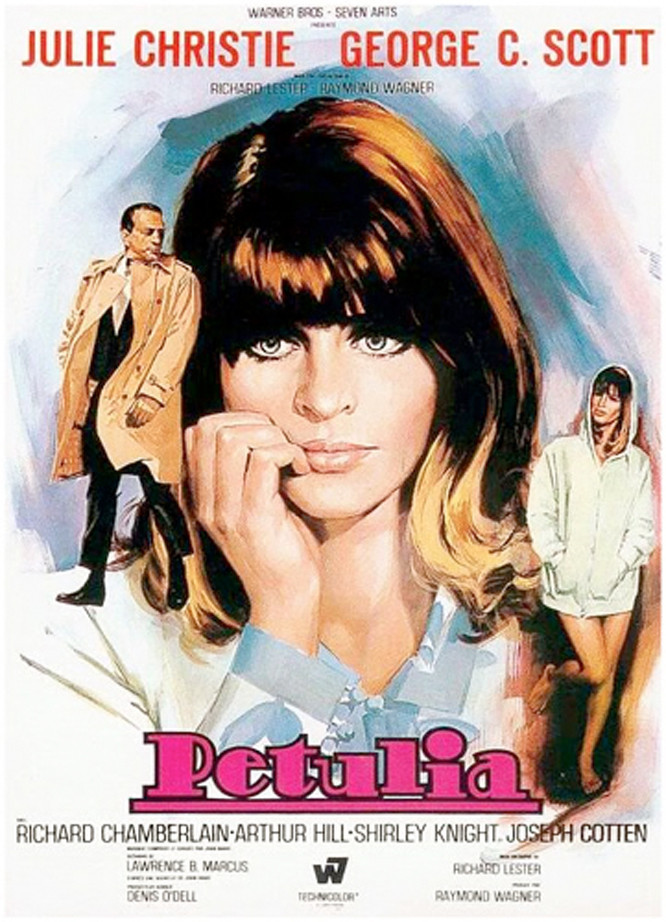

This world is brilliantly recreated in “Petulia.” Lester has buried his characters in material possessions. They live in a modern, efficient, totalitarian society of the sort that used to be called the “city of the future” by Popular Mechanics. But now the future has arrived, and we ourselves are those future citizens cooking with invisible rays and sleeping in computerized motels. “Petulia” is almost a poem to artifacts. Its hero, played by George C. Scott, is a doctor in a hospital so efficient that the patients seem incidental to the machines.

Lester’s city is also a cruel one. The film is literally filled with violence, with shattered limbs, with beatings, with the Vietnam War on television, with lies and jealousy, and with cruel insults. After Scott examines the torn leg of a little Mexican boy who has been run over by a car, he turns away. The nurse yanks at the leg: “Straighten up, you little spic.”

“Petulia” has more plot than a typical Lester film like “The Knack” or “A Hard Day's Night.” And Lester’s use of quick cuts and jumbled time, which ran wild in “How I Won the War,” is in control this time.

The story mostly involves Scott’s relationships with his ex-wife (well played by Shirley Knight) and Julie Christie (as Petulia). There are also Petulia’s problems with the Mexican boy, her husband (Richard Chamberlain) and her father (a brilliant performance by Joseph Cotten). But the details of the story are incidental.

Lester’s method, I think, is to appeal to the human animal that lives inside the citizen of society. We all live in this world, and we all participate in its indifference. But when we are confronted so directly with the soulless quality of American materialism, as in “Petulia,” we are repelled and disgusted. And that is the idea of the film.