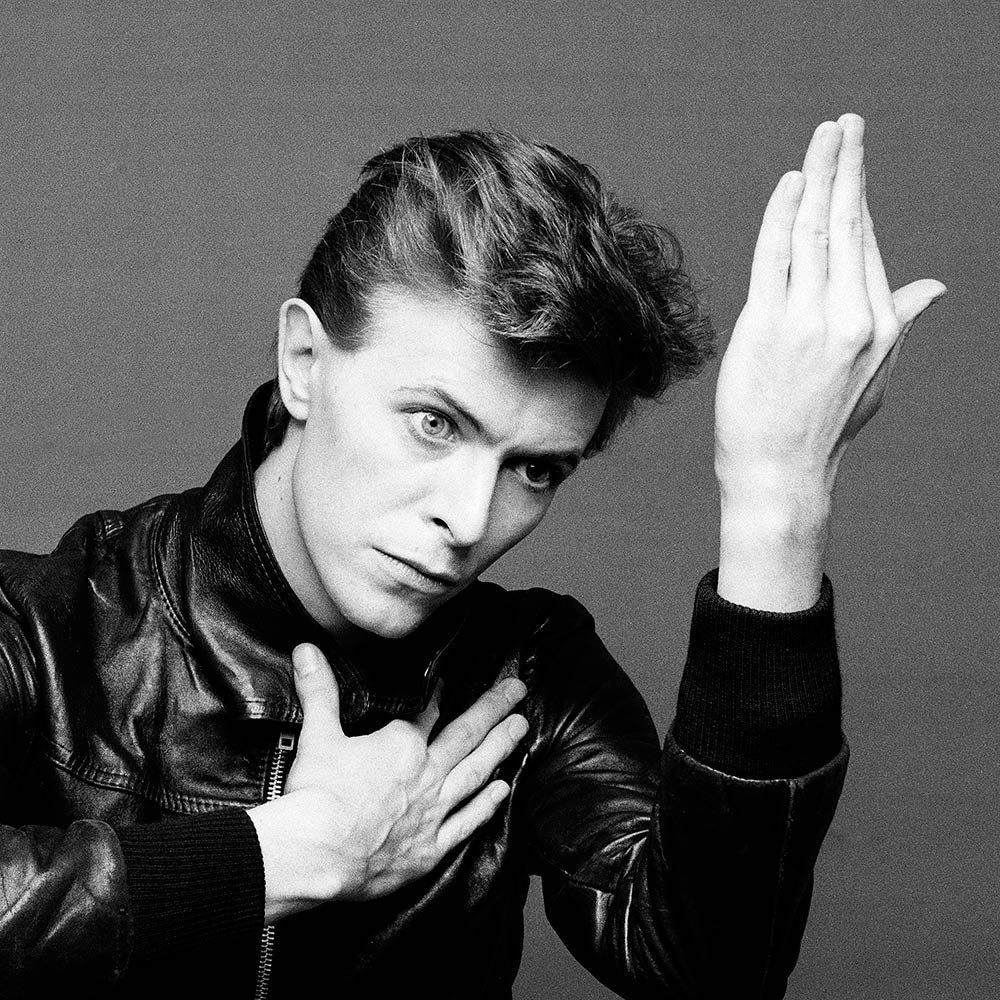

David Robert Jones is the name on his

birth certificate. Those three words don’t seem capable of containing the

multitudes of the man. The name he chose, David Bowie, conjures thousands of

men who shared the same body: Ziggy Stardust, Thomas Jerome Newton, Jareth the

Goblin King, The Thin White Duke, Vendice Partners, Aladdin Sane, Brian Slade,

Jack Celliers, John Blaylock, and on and on. He was the platonic ideal of

the rock star, a man with insatiable appetites who made the world lie down

before him, roll over and play dead. He tried everything once and reinvented

himself whenever he pleased, shedding skins and starting over as if keeping to

a tight schedule. When fictionalizing him in the 1998 arthouse touchstone “Velvet Goldmine,” Todd Haynes imagined this man as an alien dropped in from

another planet to make our world a little sweeter and sexier, and that’s been

our shared concept of the man since his first trip the United States in the

early ’70s. He did everything with finality and grace, seemingly aware that no

matter who followed him, no one would ever do it better. Cancer has taken him,

at age 69, hopefully secure in the knowledge that most of western music would

never have sounded this way without him.

He was born in Brixton in 1947 and was

barely old enough to drive when he released his first record, a kooky

self-titled folk whatsit that felt like a kid-friendly parallel to the movement

spearheaded by groups like Fairport Convention and Pentangle. His second album

underwent a number of title changes before being stamped with the title of its

hit single in 1972, “Space Oddity.” With this song, David Bowie secured his

place as a pop culture legend. To this day it’s used in films to signal titanic

shifts in perception, because no song quite captures the feeling of moving

towards the future. The song has aged better than nearly anything from that era

because it doesn’t sound like a conventional pop song. This was the first taste

the world got of his unique songwriting. Those chords, the baroque arrangement,

the sci-fi subject matter, the elastic baritone in which he wailed. It’s an

unforgettable song and it kicked off a hot streak totally unknown in the annals

of pop history. He’d release an average of an album a year from that point on

until the late ’80s, when he’d slow to an album every other year. During that

period, he abused every substance he could find, tossed ridged gender identity

in the trash, discovered Luther Vandross, collaborated with Queen, invented post-punk

music, released something like ten of the best albums in modern western musical

history, changed hundreds of lives with his music and fluid personae, and to

hear some tell it he brought down the Berlin Wall. He released his 25th and final album on January 8th, two days before he passed away, gracing us with

one last reinvention into a savvy, 21st century pop icon who fully understood

the direction music is headed. He seemed to know everything about what the

world most needed from its musical icons and always appeared happy to be able

to offer himself to the pop culture-hungry masses.

His flirtations with film and television

seem an extension of the generosity with which he approached music and his

fans. His first starring role was, fittingly, as an alien in Nic Roeg’s “The Man

Who Fell to Earth,” based on the amazing novel by Walter Tevis. Bowie’s Thomas

Jerome Newton is a pale dandy with a shock of electric ginger hair. He’s come

to Earth to try and transport water back to his home planet but becoming human

gets in his way. He develops a dependence on alcohol and an obsession with

observing human media through a bank of TVs in his flat. This seemed to mirror

Bowie’s own relation to the world he described in his music: it was big and

alienating and he both feared and desired to be a part of it. His frail figure

seemed an incompatible vessel for the decadent yearnings in Bowie’s soul.

There’s no separating Bowie from the characters he played. They all seemed to

stack up behind his unknowable eyes. This made him a totally singular screen

presence and turned everything he starred in to a cult item, worthy of

fascination and study.

His follow-up to “The Man Who Fell To

Earth” was the little-loved 1978 “Just a Gigolo,“ directed by David Hemmings, an

actor in the process of losing his Bowie-esque good looks. Fittingly, he plays

an object of lust to a host of famous vamps like Kim Novak and Marlene

Dietrich, further underlying the sense that Bowie was a timeless figure who

could have fit into any era. He would appear in Uli Edel’s

“Christiane F.”, Alan Clarke’s TV play “Baal,” where he plays a bitter,

destitute banjo-strumming poet fond of sayings like, “Our planet is full of

animals eating up its plant. One of the dimmer planets …” and Nagisa Oshima’s

“Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” the same year as his incendiary discotheque

record “Let’s Dance,” the last of his indisputable classic albums.

The year 1983 signaled the shift from his reign as a superstar among superstars into a

living legend, whose presence ensured an audience of devoted worshippers. In

“Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence” he plays a POW with eyes of two different

colours. A sadistic captain (played, symmetrically enough, by genius composer

Ryuichi Sakamoto) fixates upon Bowie’s taciturn Major Jack Celliers, and

becomes determined to be his undoing. It was a weirdly accurate portrayal of

the public’s relationship to Bowie. Fame

and money had sent Bowie into a drug-fueled tailspin from which he only rescued

himself in the late ’70s while recording his Berlin trilogy—the albums “Low,” “Heroes” and “Lodger.” “Mr. Lawrence” presents the tragedy that Bowie’s life

might have become if he hadn’t learned to deal with parasitic minders, his own

vices and the always hungry public. Another role from that year plays with the

same themes, cheekily confirming what many people might have assumed of the

seemingly ageless pop star. In Tony Scott’s “The Hunger,” he plays the vampire

John Blaylock, who suddenly succumbs to the age he’d been cheating for hundreds

of years. This also seems an eerie comment on Bowie’s stardom; that at any

moment everything that made him immortal might disappear.

Following these two hugely compelling

turns, Bowie narrowed his field, accepting roles for artists in whom he saw a

spark of the uncanny. For Jim Henson he was the king of the Goblins in the

kid-friendly “Labyrinth,” who sings and dances in an unforgettably flamboyant

ensemble. He starred in Julien Temple’s kitchen sink musical “Absolute

Beginners,” which keeps threatening to become a cult sensation but can’t quite

gather the necessary steam. He played Pontius Pilate in Martin Scorsese’s

hypnotic biblical epic “The Last Temptation of Christ.” Bowie seemed to

understand the magnitude of his stardom and what his appearances in films like

this would say to the public. It’s tough, after all, not to know that people

look at the biggest rock star in the world differently than everyone else in

the cast. So when he did little supporting turns for Scorsese or David Lynch in

“Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me,” he was engaging in his own self-mythologizing,

but also adding to the air of mystery and strangeness of the projects. When he

walks on screen in these projects, there’s still something of the alien about

him. His screen presence was rarefied and commanding. Taking on roles as hugely

public figures like Pilate, Andy Warhol (in Julian Schnabel’s “Basquiat”) and

Nikola Tesla (in Christopher Nolan’s “The Prestige”) was akin to shorthand: how

does one communicate an almost impossible celebrity just by pointing a camera

at the figure in question? Point it at David Bowie.

Naturally, Bowie had a sense of humor

about himself and his massive celebrity. He played himself several times in

everything from an episode of Spongebob Squarepants to Ricky Gervais’ series “Extras” (in which he sings a show-stopping improvised song about Gervais’ sad

sack hero, among the funniest things to air on HBO) to Ben Stiller’s smash

comedy blockbuster “Zoolander” to the 2009 teen comedy “Bandslam.” He wasn’t

pretentious and he accepted love from whatever direction it took, which meant

collaborating with everybody, whether TV On The Radio or Vanessa Hudgens. This

may be why he’s allowed his music to be used by just about everyone who’s ever

requested the rights. His music has influenced and impacted film and TV a

hundred different ways. Wes Anderson and Seu Jorge translated Bowie’s early ’70s hits into

Portuguese for the soundtrack to Anderson’s “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,” one of the

most popular and singular soundtracks of all time. The abrupt intrusion of

“Young Americans” over the end credits of “Dogville” is a right hook of ugly

irony from which audiences may never recover. His song for Lynch’s “Lost Highway” seemed designed to keep viewers in a state of suspended animation long after

they left the theatre. The sequence in Leos Carax’s 1986 “Mauvais Sang,” in which

Denis Lavant’s longing is externalized in a furious running dance to “Modern

Love,” is one of the most beautiful, powerful pieces of filmmaking of all time.

Bowie’s voice says things that people (and by extension movie characters and

screenwriters) can’t. As with his acting, his music can both ground a film or

send it to the stratosphere.

And just as everyone has their favorite

Bowie album, everyone also has their favorite David Bowie: The sturdily

strange actor; the “Labyrinth” star who hides in fond childhood memories; the

angular, sexy glam/goth icon; the man who invented and reinvented pop music; the

dapper, good-natured arbiter of all things cool, wearing old age like a pair of

velvet gloves; the gender-bending hero of the counter culture. The man who, by

becoming someone else, showed us it was OK to be ourselves, to embrace what

scares us, what we’re terrified of letting the world see. Few people ever

actually wind up being all things to all people, but he managed by never saying

no to his muse and remaining true to himself. His music has filled millions of

headphones at crucial junctures for millions of kids, and, like the answer to an

SOS, reminded everyone that there is hope; being ecstatically weird is more

than OK. He changed the world through his music, and just by being David Bowie

when he could have been David Robert Jones. His 1977 album “Low,” with its

paranoid synth soundscapes and drums amplified and altered by the Eventide

harmonizer, was the primary influence on the band Joy Division as they recorded

their groundbreaking first record “Unknown Pleasures.” Meanwhile Bauhaus was

covering “Ziggy Stardust,” and Talking Heads had their sound changed by Bowie’s

collaborator/producer Brian Eno using methods developed during the creation of

the Berlin albums. In short, a huge swath of the post-punk movement owes Bowie

a debt of gratitude and that was the music of my adolescence, the stuff I

listened to during the worst of my aimless, somber college years and during bad

break-ups.

David Bowie created music for every circumstance. Soul, dance and glam for the

highs, moody, pulsing electronica for the lows. We may never look this

generous, gorgeous genius in the eye again, but he’s curated entire lives yet

to be lived and changed what it means to be an artist. Summing up his

achievements is a fool’s errand because he did it all, so maybe it’s best to

simply say the world will always be richer because he was here.