Anyone who has ever painted or drawn knows the experience of dropping out of the world of words and time. A state of reverie takes over; there is no sensation of the passing of hours. The voice inside our head that allows us to talk to ourselves falls silent, and there is only color, form, texture and the way things flow together.

There is a theory to explain this. Language is centered on the left side of the brain. Art lives on the right side. You can’t draw a thing as long as you’re thinking about it in words. That’s why artists are inarticulate about their work, and why it is naive to ask them, “What were you thinking about when you did this?” They have given it less thought than you have.

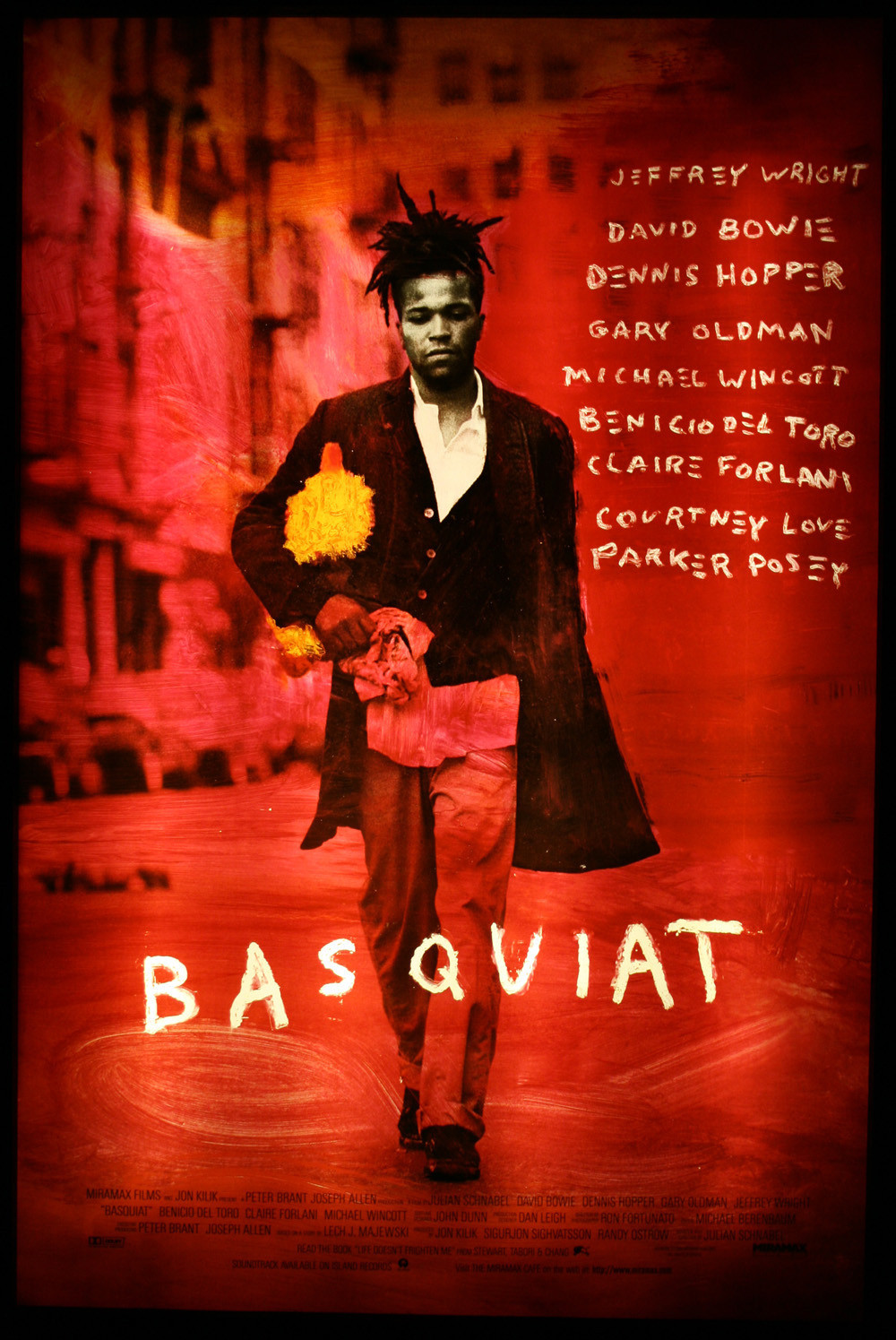

Jean-Michel Basquiat seems to have spent most of his brief life on the right side of the brain. Only another artist could understand that, and “Basquiat” is the confident, poetic filmmaking debut of the painter Julian Schnabel, who was a friend of Basquiat’s. As Schnabel remembers him, he is a quiet, almost wordless presence, a young man who rarely says what he is thinking and often deliberately chooses to miss the point of a conversation. He is dreamy, sweet, and pensive. There are deep hurts and angers, but he often chooses to turn a passive mask to the world.

Basquiat, born in New York to middle-class parents, was an important artist in the generation that exhibited in Manhattan’s SoHo district around 1980. His anonymous work was known earlier: He was a graffiti artist whose neatly printed legends, signed “SAMO,” were found all over New York. On April 29, 1979, at a party opening the Canal Zone (a New York art space), Basquiat identified himself as SAMO, and within a short time his paintings were finding collectors.

His work seemed to accumulate on the surfaces he found around him. He painted on boards, walls, canvases, on the dress of his girlfriend, and even on her paintings. His work assembles areas of bold color with more detailed areas of text, figures, designs and scribbles–blueprints for a world in his mind. He fell into success with astonishing ease. His first sales came after he approached Andy Warhol and a famous collector (played by Dennis Hopper) at a restaurant table, and they bought his decorated postcards.

Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright, who gives a performance of almost mystical opacity) was at that time only a few months out of homelessness; he had lived for a time in a cardboard box. He drifted away from his middle-class home and into a world of his own, and even to his girlfriend Gina (Claire Forlani) he remained an enigma. His attention was inward; like all drug users, he focused much of the time on the way he felt, or didn’t feel.

The New York art world quickly makes Basquiat a star. His work is good (when you see it in the movie, you can feel why people liked it so much), but his story is better: from a cardboard box to a gallery opening! A dealer named Rene Ricard (Michael Wincott) spots his work at a party, delivers the ancient pitch “I will make you a star,” and does. “You’re named SAMO? Sounds famous already. You got a real name?” When he learns that Basquiat also performs in a band, he frets, “Are you Tony Bennett? Do you sing onstage and paint in your spare time?” Basquiat soon becomes a close friend of Andy Warhol’s, who in a remarkable performance by David Bowie comes across as preternaturally detached (that’s not news) but also as gentle, open, accepting, and instinctively perceptive about new directions in art. When Basquiat is depressed by a magazine article depicting him as Warhol’s “mascot,” a mutual friend tells him, “Andy has never asked me for a thing except to talk to you about getting off drugs.” That Basquiat will not do. Drugs are the center of his existence. His best friend from the early days, a Puerto Rican painter named Benny (Benicio Del Toro), finally drops him because of his self-destructiveness. Gina finds him nearly dead after an overdose. It is clear to everyone he is in trouble. But by now Basquiat is in a mental land of his own. We learn that his mother is a mental patient, and there is a poignant late scene as he tries to break into the shuttered convent where she once lived; turned away from the chained gates, he wanders the streets in pajamas, headed for homelessness again.

Schnabel knows the New York art scene intimately (his own paintings appear in the movie as the work of a character played by Gary Oldham), and he shows us the agents, the critics, the collectors and the dealers (Parker Posey plays Basquiat’s dealer Mary Boone). He knows the acquisitive greed of collectors and dealers, and shows Basquiat drawing in plum sauce in the guest book at Mr. Chow’s and another guest at the table tearing the page from the book (is it framed on somebody’s wall even now?).

Schnabel also has a good ear for the lingo. Racism is not racism, apparently, if it is expressed with the right tone of bored sophistication, and so we hear Basquiat’s admirers saying, “This … is the real voice of the gutter!” At another point he is described as “the pickaninny of the art world.” He hears, “There has never been a black painter who was considered important.” Actually he is a wonderful painter, and the right side of his brain is rarely wrong, as he demonstrates in a remarkable scene with Warhol where he fearlessly takes a brush and applies a large white area to one of Warhol’s Mobil flying horses. Warhol lets him: “I think you may be right about the white.” But there is always madness there. Schnabel remembers that Basquiat often talked about moving to Hawaii, and shows waves and surfers in the sky above Manhattan. He shows Basquiat painting a stack of car tires, and then seeing them transformed into a flowering tree. At the end, he was wearing boat like wooden shoes on which he had painted “Titanic.” He died Aug. 12, 1988. He was 28 years old.