Godard is a contemptuous artist, too. Forget “Le Mepris.” Ever see “Weekend”?

We heard a lot in 2006, as we do every year, about nasty filmmakers who were said to have viewed their characters (and, hence, their audiences) with contempt, or who “made fun of” them, or treated them with condescension, or who just don’t seem to like them very much. Across time, such charges have been leveled at Stanley Kubrick, Robert Altman, Christopher Guest, the Coen Bros., Todd Solondz, Sacha Baron Cohen, and many other artists — especially those whose work has tended toward the comic or caricaturish. And then there’s all of film noir to consider, a whole kind of moviemaking that does not view the human animal with kindness or affection.

In answer to specific allegations of of alleged contempt (such as Jonathan Rosenbaum’s characterization of Altman’s attitude toward Lady Pearl in “Nashville”), I have tried to explain why I think such charges are false, or at least misguided. It seems to me, in these cases, that the contempt being expressed is more likely to be that of the critic for the director or film (or reader) than that of the director for the character or the audience (unless we’re talking about a movie by, say, Alan Parker). But it’s impossible (and futile) to argue with a blanket statement like: “The Coens mock everybody. They’re laughing at the audience!” — meaning, of course: “They’re laughing at me!” (please read in the voice of Piper Laurie in “Carrie”). My response is: 1) that’s a rather vague aspersion; 2) if you got the joke you wouldn’t feel like you were being laughed at; and, 3) yeah, it’s true. Many forms of comedy — satire, parody, etc. — contain an element of mockery. Even contempt.

So, I’m here to speak up for contempt! (How very contrarian of me!)

The rich, powerful and pretentious are obvious (and ripe) targets for humor and derision. Their problem is that they’re just people, with flaws like everybody else, only magnified (and made more irritating and dangerous) by their position in society. They deserve to be knocked down a few notches. But you don’t have to be rich, powerful or pretentious to be a hypocrite, or a boor, or a twit, or an oaf, or a cretin. You don’t have to possess great wealth or celebrity or influence to be smug, stupid, petty, ignorant, pathetic, tasteless, crass, callous, crude, or just downright annoying — and, thus, worthy of comic derision. Such people really exist! I’ve seen them with my own eyes! What’s more, I’ve been them!

“Hey, look at those assholes over there. Ordinary f—-in’ people. I hate ’em.”

— Bud (Harry Dean Stanton), “Repo Man” (1984)

“Hell is other people.”

— Jean-Paul Sartre, “No Exit” (1944)

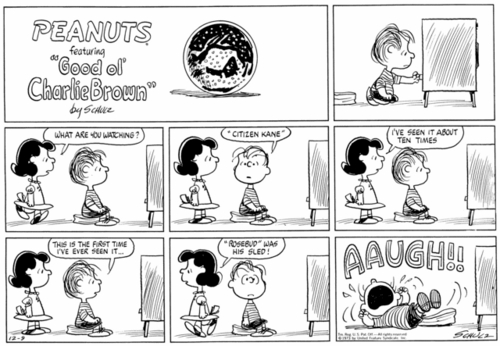

I sometimes wonder if those who worry about expressions of contempt for characters (particularly “ordinary people”) in movies have ever had jobs in which they had to deal with the general public. Or have ever attended some kind of party or social function at which they have met some people they would rather not have met. Is this not part of the human experience? Don’t most people have some pretty awful qualities? Why should an artist be expected concentrate on their benign or “sympathetic” traits — or to come up with some kind of artificially “fair and balanced” view of them? Some people’s most interesting characteristic is that they are idiots. Or worse. Did you like “Seinfeld”? Those characters were despicable in every way. Some people thought that was why they were funny.

Is misanthropy not the most universal and understandable of all sins? For all our achievements and evolutionary refinements, we are a pretty damnable species. And, as the only one capable of (and perhaps unwittingly committed to) destroying all life on our own planet, we are also the richest, most powerful and pretentious. Don’t we deserve to have a laugh at ourselves — or, at least, at those idiots right over there?

P.S. I am reminded of the words of Luther Ingram and Mack Rice, as sung by the incomparable Mavis Staples (and, yes, I’m going through one of my periodic obsessive Stax phases, so get used to it):

Keep talkin’ ’bout the president won’t stop air pollution

Put your hand over your mouth when you cough, that’ll help the solution

Mavis means you. And she’s singing in the context of a Christian family gospel/soul group. Good gosh a’mighty, now — even the Staple Singers aren’t afraid to make the average person the butt of an occasional, rather contemptuous, joke. Amen to that.

December 14, 2012