Over the past 12 months, RogerEbert.com has compiled a wide array of excerpts from excellent books penned by some of the most gifted cinephiles in print. For the first installment of our 2014 Holiday Gift Guide, we have assembled enticing passages from all of the books featured this year with links that will direct you straight to their Amazon pages. Click on the book title, and you will be able to read the full excerpt.

Meryl Streep: Anatomy of an Actor by Karina Longworth

Ironically, Streep was finding it more difficult to play a person who had lived than a completely fictional character. The few tangible clues Silkwood left behind were not necessarily trustworthy. Streep was haunted by a widely circulated image of the woman she was playing, taken from Silkwood’s workplace ID. “She’s already a ghost in that portrait,” Streep thought. “She’s there, and she’s not there.” At one point, the actress listened to a tape of Silkwood’s voice, made from a phone call with a union lawyer. “Her voice was quite a lot lower than mine, and she spoke r-e-a-l slow.” She listened to it again and again, but ultimately decided to forget it. “Maybe the phone call was in the middle of the night and she was tired; maybe it was her recorder. As it was, it was wrong dramatically for the movie.” The experience made Streep realize the goal behind her performance: “I wasn’t just trying to replicate her. We were trying to imagine, or invent, emotional reasons for her, working backward to see if we could discover why she did all that she did.”

Steven Spielberg and Duel: The Making of a Film Career by Steven Awalt

The story of “Duel” drew Spielberg in personally on a couple of levels. “While I expected a well-written and gripping narrative, nothing prepared me for the relentless, unforgiving force I encountered. The most frightening aspect of the story for me, and a device put to chilling use in the screenplay for “Duel” as well, was the fact that this maniacal truck driver went unseen the entire story. . . . Equally disturbing was the seemingly random selection of Mann’s car among all those on the road, a chilling notion even in today’s road rage–filled society.” It was this senseless targeting of Mann that really hit home with Spielberg, himself victimized by bullies as a young boy for his less-than-athletic looks and, worse, for his Jewish heritage.

It Doesn’t Suck: Showgirls by Adam Nayman

Like a shark sniffing blood in the water, a man cruises by and propositions Nomi, telling her that he has some ideas about how she can make her money back. “Sooner or later, you’re going to have to sell it,” he calls as she strides away, seething. Losing the money was a wake-up call for Nomi that nothing in Las Vegas is going to be as easy as it seems, that the town’s M.O. is to give you little glimpses of victory before snatching them away. We won’t know just how deeply Nomi is stung by the catcaller’s insinuation until much later in the movie, but we’ve definitely seen enough, even in this one brief encounter, to validate Jacques Rivette’s claims that “Showgirls” is “about surviving in a world populated by assholes” — not only this guy, with his slick haircut and shirt unbuttoned to reveal a cheap gold chain, but also Jeff, who has swiftly and predictably made off with Nomi’s suitcase for the low price of ten bucks.

Shadow Philosophy: Plato’s Cave and Cinema by Nathan Andersen

Films present us with image and sound. We see things – objects, places, people – moving about, doing things, and interacting. We understand what we see. For the most part, it makes sense to us. We know what the things we see on screen are, or at least what kind of things they are, and the kinds of things they do. We notice, or at least feel, the differences between different styles of camera movement. When moving images from different perspectives are joined together, one after another, we can usually tell when they’re meant to suggest a sequence of events, when they’re meant to suggest simultaneity, when they belong to different locations, or when they belong together as different perspectives on the same situation. Usually, the sounds we hear are easily linked to the images. We hear words and know who is speaking. We hear music and can read the cues to know whether it is something the characters hear as well, or whether it is music for our ears only, meant to accompany what we see, adding mood or rhythm. We make sense of what we hear and see. The specifics vary, but there are a range of repeating forms in cinema that are significant to us, both because we have grown up in a world that we’ve learned to make sense of and because a significant part of growing up in the modern world is to become familiar with moving images and their many variations.

Vanessa: The Life of Vanessa Redgrave by Dan Callahan

The Devils” is certainly the best-written of all Russell’s films, the most disciplined, the only one that can claim a real horror at how twisted human beings can become. He makes a few mistakes, especially in falsely portraying Louis XIII (Graham Armitage) as a woman-hating homosexual who, in the first scene, does a “Venus on the Half-Shell” routine for Cardinal Richelieu (Christopher Logue), but Russell seems inspired by Derek Jarman‘s extremely suggestive sets, especially the convent, which resembles a vast black-and-white bathhouse. “I know originally they had them looking for medieval times in France, to shoot on location,” said Redgrave. “And I remember vividly that when I heard we’d be shooting in Pinewood studios, I had a sinking stomach and thought, ‘Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear.’ But of course, when I saw Derek Jarman’s designs I knew that we were into something really extraordinary because Ken and he obviously had a very, very marvelous synthesis going between the links with the white tiles that meld with the meticulous costumes of the court and so on.”

Psycho-Sexual: Male Desire in Hitchcock, De Palma, Scorsese, and Friedkin by David Greven

De Palma’s relationship to Hitchcock, derided for so long, has longstanding precedents. Structurally and stylistically, his engagement with the genre of Hitchcockian suspense is analogous to the classical Roman tragedian Seneca’s revisionary reimagining of Greek tragedy. Seneca’s elaborate variations on Greek tragedy foreground and intensify the physical and emotional violence of the genre. New rivers of blood gush through Seneca’s revisionary tragedies, adding a corporeal intensity to their austerity that is analogous to De Palma’s blood-thriller versions of Hitchcock. Hitchcock has often, and rightly, been called the cinematic Shakespeare. In almost every one of De Palma’s thrillers, an image of a bloody hand—in torment, in protest, in suffering—rises up, a figure from tragedy in its Shakespearean as well as classical form. De Palma’s revisionary Hitchcock recalls as well the agon that antebellum American authors such as Edgar Allan Poe and Herman Melville had with Nathaniel Hawthorne, the Apollonian counterpoint to their Dionysian excessiveness. De Palma is an artist whose Dionysian sensibility—evident from “Dionysius in ’69” (1970), his underground film version of “The Bacchae,” to his 2002 Hitchcockian thriller, “Femme Fatale”—combines the comic and the tragic, the controlled and the excessive.

Make Art Make Money: Lessons from Jim Henson on Fueling Your Creative Career by Elizabeth Hyde Stevens

On Henson’s lunch breaks from “The Muppet Show,” he would eat, conduct a writers meeting, and field business calls. When he took a cruise on the QE2 with his wife, he took the whole company with him to work in London. On his 29th birthday, he wrote a script for “Alexander the Grape,” an unpaid project. The work was his cake and streamers. The work was his gift to himself. Henson turned forty on a plane trip and spent fifty on a “vacation cruise” with his agent. Jerry Juhl said, “Year after year, we watched him push himself beyond what we could possibly imagine. You had to try to keep up.” Henson himself denied being a workaholic. “I work a great deal,” he said, “but I enjoy it.” Frank Oz has said, “It’s hard for people to understand the reason Jim worked so hard is he loved it.” This seems like a genuine sentiment, but what does it mean? What do you call someone who works all the time but is not a workaholic? And how would you ever distinguish one from a workaholic?

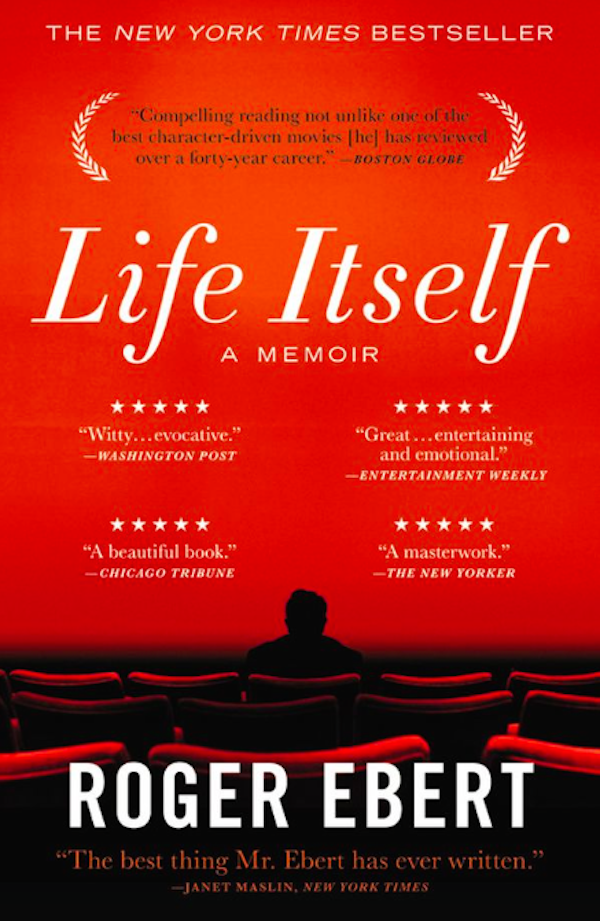

I was born inside the movie of my life. The visuals were before me, the audio surrounded me, the plot unfolded inevitably but not necessarily. I don’t remember how I got into the movie, but it continues to entertain me. At first the frames flicker without connection, as they do in Bergman’s “Persona” after the film breaks and begins again. I am flat on my stomach on the front sidewalk, my eyes an inch from a procession of ants. What these are I do not know. It is the only sidewalk in my life, in front of the only house. I have seen grasshoppers and ladybugs. My uncle Bob extends the business end of a fly swatter toward me, and I grasp it and try to walk toward him. Hal Holmes has a red tricycle and I cry because I want it for my own. My parents curiously set tubes afire and blow smoke from their mouths. I don’t want to eat, and my aunt Martha puts me on her lap and says she’ll pinch me if I don’t open my mouth. Gary Wikoff is sitting next to me in the kitchen. He asks me how old I am today, and I hold up three fingers. At Tot’s Play School, I try to ride on the back of Mrs. Meadrow’s dog, and it bites me on the cheek. I am taken to Mercy Hospital to be stitched up. Everyone there is shouting because the Panama Limited went off the rails north of town. People crowd around. Aunt Martha brings in Doctor Collins, her boss, who is a dentist. He tells my mother, Annabel, it’s the same thing to put a few stitches on the outside of a cheek as on the inside. I start crying. Why is the thought of stitches outside my cheek more terrifying than stitches anywhere else?

Film Firsts: The 25 Movies that Created Contemporary American Cinema by Ethan Alter

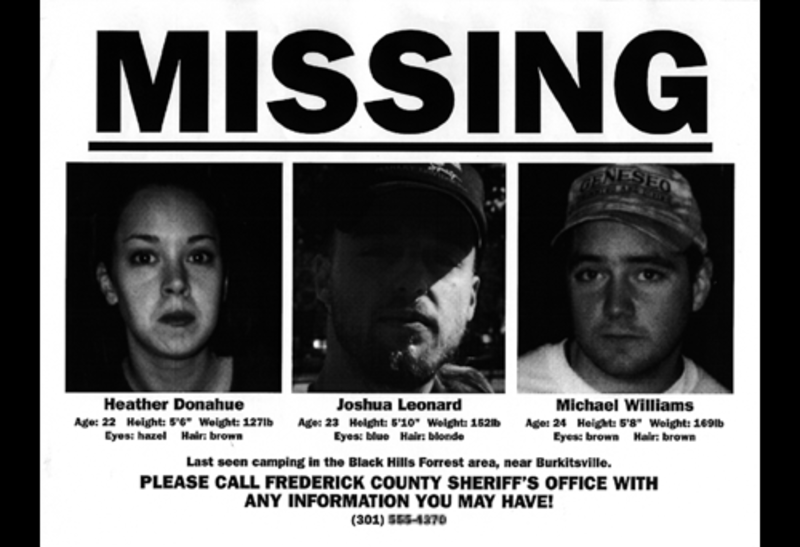

And yet the impressive thing about “The Blair Witch Project” is that, while you’re watching it, you don’t see the strings. Sure, there are cracks in the scenario if you laser in closely enough, especially during repeat viewings. But all that advance legwork that the filmmakers put in lends the film an internal consistency and a narrative drive that its descendants in what has become known as the “found-footage” genre often lack. A found-footage descendant like 2007’s “Paranormal Activity,” for example, operates mainly on a scare-to-scare basis, using the found-footage aesthetic (commonly defined by a first-person point-of-view camera, jumpy editing, and mockdocumentary interviews and/or confessionals, among other elements) to stage effective “Boo!” moments, but not necessarily putting a great deal of thought or effort into what comes between them. In contrast, “The Blair Witch Project” doesn’t isolate its predesignated scary bits—the scenes the filmmakers have specifically designed ahead of time to elicit screams from the crowd—from the rest of the narrative; instead, the whole movie flows together, building naturally and inevitably toward the characters’ horrific fates.

Robert De Niro: Anatomy of an Actor by Glenn Kenny

Johnny is putting the last nail in his coffin, and he follows this with one more gesture of bravado, the pulling of the gun, which Michael says Johnny doesn’t have “the guts” to use. This is what one could conceivably call “very punk rock.” It is likely a complete coincidence that the debut album by the proto-punk band the New York Dolls was released only a few months before “Mean Streets”” hit theaters. But one doesn’t have to look too far beneath the big hair and the glitter-rock trappings to see the don’t-give-a-fuck affinity between Johnny Thunders (born John Anthony Genzale Jr., in Queens), that band’s guitarist, and De Niro’s Johnny Boy. The pre-punk affinity is prophesied more clearly, and threateningly, in Travis Bickle’s mohawk in “Taxi Driver.” By that time Thunders had ditched the Dolls and formed his own Heartbreakers, whose anti-anthemic “Born To Lose” could have served as Johnny Boy’s theme music just as aptly as “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.”

Tom Cruise: Anatomy of An Actor by Amy Nicholson

The role was a high school kid desperate to lose his virginity. A friend suggests a hooker, and over the course of a crazy weekend the innocent boy falls—temporarily, at least—for the older woman who takes him to bed. His agent said he’d be a fool to turn down the part. It would be his first starring gig, teen sex comedies were a huge market, and frankly the twenty-year-old bit player was in no position to say no. So Tom Cruise said yes. And the decision defined the rest of his career. The film was “Losin’ It” (1983), and Cruise was embarrassed by it before it even hit theaters, where it did a miniscule $1.26 million. He didn’t do press—he didn’t even go to the premiere. Less than a year later, he openly groaned it was “a gross mistake I won’t make again.” He hasn’t. Just two years into his career, Tom Cruise made a vow that he has never broken. “I learned a great lesson in doing that movie. I realized that not everybody is capable of making good films,” said Cruise. “I decided after “Losin’ It,” I only wanted to work with the best people.” He has.

Showrunners: The Art of Running a TV Show by Tara Bennett

JANE ESPENSON, Showrunner (“Caprica,” “Husbands“): “When I came up in TV, dramas were in four acts. ‘Buffy The Vampire Slayer’ was four acts and that means there were three commercial breaks. Let’s picture a loaf of bread: the three cuts make four pieces of bread, and so you got used to structuring a story like that. There’ll be a big turning point right in the middle of the loaf that changes everything, so it’s not even going to be pumpernickel anymore when you come back to this loaf. Then it started changing, and we got to five acts, and then six acts, and now some shows are six acts and a teaser, or seven acts and a teaser. There’s this inflation because they want to put more commercial breaks in, so you end up having to turn your story more often. You [write] six pages and you stop for a commercial break. Now you need that next six-page chunk when you come back to feel a little different in flavor than the first six pages, or that act break will feel like it didn’t quite land. You end up having to make all these little turns in the story. The problem is you end up with a very shallow, twisty story.”

Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed: Conversations with Paul Cronin

We weren’t allowed to bring our own boots and parkas; everyone is issued with these things upon arrival. If you use regular boots, you might be able to hold on to your toes down to about –25ºC, but after that frostbite sets in. We were sure to test our camera and sound recorder in a facility in Los Angeles at temperatures of around –20ºC. I took two recorders with me to McMurdo, but almost immediately had to abandon the more sophisticated one because it had tiny buttons and was impossible to operate while wearing gloves. As soon as we arrived at McMurdo we lost about a week because we were obliged to undertake a mandatory survival course – which involved learning to build trenches and igloos – a course in radio communications, and one in snowmobile riding. I found the authorities there too concerned for my personal safety, and resented having to spend so much time on these things; it was a little excessive for my liking. Having said that, three days after arriving I had an accident on a steep slope when an eight-hundred pound snowmobile rolled over my body. For weeks afterwards I was sore everywhere and could barely bend down to tie my shoelaces.

Approaching the End: Imagining Apocalypse in American Film by Peter Labuza

Thus, if we separate the images of “Days of Heaven” from the actual A-to-B-to-C plot, we find a noir narrative taking shape, and I think the interplay between this noir plot against the Malickian backdrop is key. The film follows lovers on the run Bill and Abby (along with Bill’s young sister, Linda) as they make their way west after a murder in Chicago. Bill then attempts to steal the fortune of a dying farm owner through a plan of sexual betrayal using Abby. What is essentially at odds here is that this land—the Texan plains in the 1910s—is supposed to represent an escape from the pains and chaos of the city, a glorious Eden. Instead, these characters fall into the same traps as before, and the physical territory that promised openness and life becomes one of destruction. “Days of Heaven” thus might be one of the most cynical noirs because it essentially translates noir out of the confines of the 1940s and -50s urban moment and into the most idyllic of spaces—anything is now corruptible.

A Single Consciousness: The Cinema of Terence Davies by Michael Koresky

“The Terence Davies Trilogy,” as it was called when released in 1984, is a compilation of three black-and-white shorts shot on 16mm over the course of seven years—”Children” (1976), “Madonna and Child” (1980), and “Death and Transfiguration” (1983)—all of which evince compositional poise and thematic audacity. The most strongly gay-oriented films of Davies’s career, these were made years before there was anything approaching an alternative queer-cinema movement. The trilogy’s importance to Davies’s artistic mission is solidified by his choice to further explore its main character, milieu, theme, and tripartite structure in his only novel, “Hallelujah Now” (1983), which similarly delves into its protagonist’s profound guilt and trauma over his homosexuality in an achronological, stream-of-conscious manner that effectively destabilizes the present.

The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion by Jason Bailey

To maximize your laughs, you had to have a persona. And from that realization, “Woody Allen” was born. He wore thick-rimmed black glasses, the telltale accessory of a bookish intellectual, a notion furthered by his frequent literary allusions and surrealistic wordplay. Part and parcel for the comic intellectual, then, was the presumption of physical weakness, the image of the meek, bullied nebbish, an image further bolstered by the slight frame and thinning hair that made him a combination of 98-pound weakling and red-headed stepchild. He would feign braveness, but back off immediately—in both physical altercations with the same sex and romantic entanglements with the opposite, talking the game of a white-hot lover but, in practice, more of a horny bumbler. And then there was the voice—“a nice Jewish boy gasping for air,” as writer Foster Hirsch put it—a nasal Brooklynese that danced right up to the edge of a whine. His onstage and onscreen patter was a tumult of stammers and mumbles, charging and backtracking, pausing and rephrasing, all little tricks that created the impression of nervousness and aimlessness, yet diverting us (his magician’s training, that) from noticing the clever construction of the set-ups and punch lines, or how masterfully he deployed those “um”s and “tch”s as part of the musical rhythm of his joke delivery.

Missing Reels by Farran Smith Nehme

The woman had lived in the building so long that it was her own name, Miriam Gibson, on the buzzer label, and not some forgotten former tenant. She must have been in her seventies, but she was the most beautiful old lady Ceinwen had ever seen. Her face was barely lined, with fine features and pale brown eyes; she wore her hair coiled at the neck. Miriam stood straight. She wore tailored dresses and suits with scarves, everything perfectly pressed and matched. None of the elastic Ceinwen had quietly shuddered over as Granana wheezed around the house. Miriam lived on the floor below them. Talmadge, Jim, and Ceinwen hated the climb to their place so much that if someone forgot to buy coffee or cigarettes on the way in, it would take half an hour of arguing to decide who had to run to the bodega. Miriam climbed slowly, but when she reached her door, she seemed no more ruffled than if she had just crossed the hall. Their apartment was a sixth-floor walkup, but it had two real bed- rooms and a double living room with a large alcove that could be closed off with screens for another roommate. There were no closets.

Rainer on Film: The Night of the Hunter by Peter Rainer

A big reason “The Night of the Hunter” seems so fresh—even though it was shunned by the public upon its release in 1955—is because it lacks the well-oiled sameness of mood that even the most notable Hollywood movies of its time had. Its crazy quilt emotionalism is much closer to how we experience the world now. Still, the extreme mood swings in “The Night of the Hunter” have always disrupted audiences, even its most fervid appreciators. The movie is amazingly soulful and yet, unless you get the hang of it, it can be baffling. When I saw the film at an evening tribute for its star, Robert Mitchum, not long before he died, some in the audience howled in all the “wrong” places, convinced that the preacher’s high dudgeon and Laughton’s storybook symbolism were flubs or, even worse, put-ons. But the howls, if I’m not reading too much into them, also carried an undercurrent of discomfort and perplexity. In the air that evening was at least the grudging realization that “The Night of the Hunter” was no ordinary movie, bad or otherwise. Those members of the audience who think they’re smarter than this film always end up outsmarting themselves.

Harmony Korine: Interviews by Eric Kohn

A hit at Sundance and Cannes, “Kids” transcended the perceived limitations of its NC-17 rating and grossed $20 million at the box office, effectively turning Korine into a major pop culture figure. That same year, he appeared on Late Night with David Letterman and mystified a nation with a combination of wide-eyed innocence and scrappy demeanor. The media loved Korine’s playful behavior and foul mouth. He expressed adoration for vaudeville and certainly put on a good show, tap dancing for one interviewer and harassing pedestrians while hanging out with another. He was practically an auteur before even directing his first film. The next few years unfolded in a whirlwind of creativity and scandalous gestures. Korine’s directorial debut, “Gummo,” was shot in rundown Nashville neighborhoods on 16mm, eschewing plot for bizarre asides and eccentric character sketches. The New York Times’ Janet Maslin infamously called it the worst movie of the year, an assertion that “Gummo”’s producers considered placing on its poster. There’s no doubting the potency of a movie so dense with images and information, which dances a line between experimental documentary and lyrical portrait of an alienated lower class with such riveting intensity that it transcends any easy categorization.

Eat, Drink & Remarry by Margo Howard

“During that summer in Washington, I actually felt like an independent grown-up. And that summer was the first time I met someone who I seriously thought of marrying. Three previous proposals had been nonstarters and were certainly never taken seriously by me. One came from a Chicagoan in his late ‘thirties with whom I went out maybe half a dozen times. He was rumored to be gay and was a real fashion plate who loved to cha-cha. I was 18 (still in high school!) when the dancing fashion plate popped the question and I, of course, declined, recognizing that while I would have given him hetero cred, I did not need someone to pick out my clothes. And I also knew I was never going to marry anybody when I was 18. Another suitor was a visiting sociology professor at Harvard whose work involved drug addicts and prostitutes and was six years junior to my father. I declined that one as well, recognizing that he was too old, although that was a real romance … . for a semester. The third proposal came from a man who looked good on paper in terms of profession and family—and he was handsome, to boot—but whose ardor I was unable to return. Although it was a real romance, my inner radar told me he was a little boring for the long haul, and while he was intent on marrying me (always flattering), instinct told me he was not the one.”

Asghar Farhadi: Life and Cinema by Tina Hassannia

“The Past” was Asghar Farhadi’s first film made outside of his home country, a production that reconfirmed his position in the international film scene. Though “A Separation” made a bigger splash, “The Past,” a collaboration with European producers, crew, and a big-name cast, was a sign that the filmmaker was ready and capable to work outside of his comfort zone. The film also affirmed that, despite the cultural specificity of his previous work, Farhadi could adapt his dramatist style for any setting—even a city that had been represented in cinema countless times: Paris, France. The production of the film was a bit of a challenge for the filmmaker, who was used to working in his native tongue. Having an interpreter onset was necessary for him to communicate clearly with his crew and especially his cast, with whom he worked for months in rehearsals and whose lines were almost entirely in French. Furthermore, the production scale was larger (more crew members, a bigger budget) and Farhadi had to navigate a foreign production system. Despite the cultural barriers, Farhadi says he welcomed the challenge