John Cassavetes’ “Husbands” is disappointing in the way Antonioni’s “Zabriskie Point” was. It shows an important director not merely failing, but not even understanding why. “Husbands” has all the confidence of Cassavetes’ masterpiece, “Faces,” but few of the other qualities of the film that preceded it. It has good intentions, I suppose, but it is an artistic disaster and only fitfully interesting on less ambitious levels.

Still, it comes to us with incredibly good New York notices, a specimen of what Pauline Kael calls media-hype. Every season there are one or two films that are decreed as great by the New York critical establishment, against all common sense. The best critics, like Kael, weren’t won over by “Husbands,” but the Luce magazines apparently decided by fiat that it was superb. Life had Cassavetes on its cover, and seldom has Time given a better review to a worse movie.

Cassavetes once again uses what I guess you’d call pseudo-cinéma vérité although his film is acted by professionals and (allegedly) scripted in advance, it’s given a documentary look. “Faces” was, too. But “Faces” actually was photographed in 16 mm., with available light and sound, so of course it looked that way.

With “Husbands,” a deliberate effort has been made to simulate the 16-mm, cinéma vérité look, even though the graininess isn’t necessary. That isn’t dishonest — a director has a right to do anything he can to make his film work — but it doesn’t grow organically out of the material. Nothing in this film, in fact, seems organic to it; the idea, the style, the narrative, the acting, all seem laid on to a reluctant film. “Faces” was all of a piece; “Husbands” is in pieces.

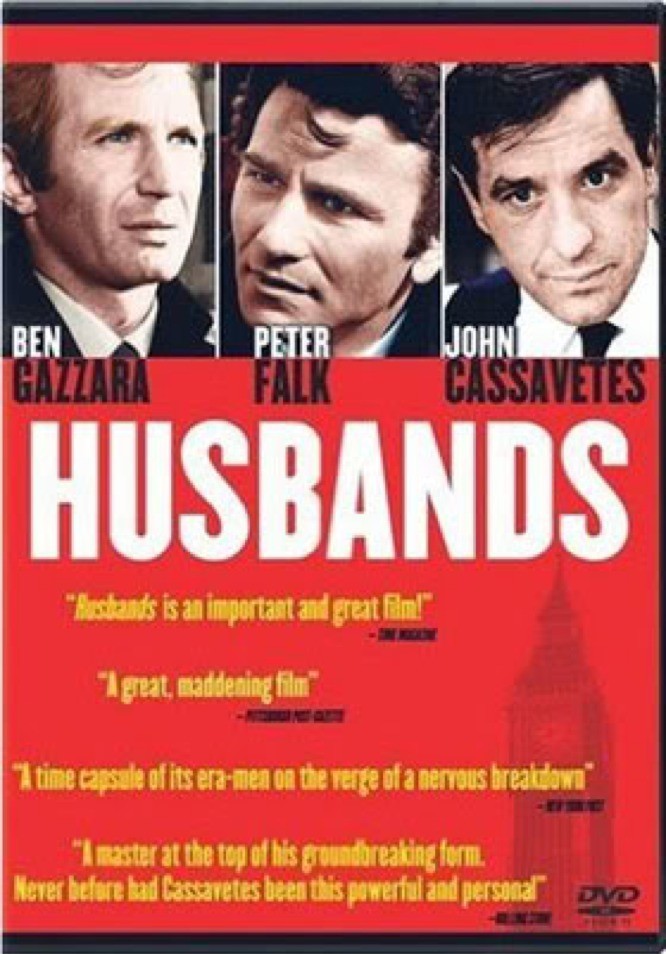

The story sounds promising when you hear it. Three friends (Cassavetes, Ben Gazzara, Peter Falk) mourn the death by coronary of a fourth. Mourning leads naturally into drinking, and after an extended binge (including the singing of maudlin songs, the expression of undying friendship, copious beer drinking and even more copious vomiting) the friends find themselves flying to London. They pick up three complaisant girls (rather easily, it seemed to me), and in wine, gambling and lovemaking they seek truth.

Fair enough. Here we have three characters on the edge of middle age, and the fact of their friend’s death is the shadow of their own. Considering the talent involved in the making of “Husbands,” it is surprising that so little was made of such material. There are a lot of problems. One is with the script. “Faces” was almost totally scripted, and seemed almost totally improvised. A really excellent script should always seem improvised, of course, to the degree that the actors seem to be saying real things and not reciting dialogue. “Husbands,” which Cassavetes takes a writing credit for, sounds improvised in the worst sort of way.

There are long passages of dialogue in which the actors seem to be trying to think of something to say. This in situations where the words should flow naturally (is a drunk ever at a loss for words?). There are lines like: “You know what you are? You’re a … you’re … I’ll tell you what you are … you’re … I wish I could think of what you are.” Followed by the actors breaking up and slapping each other’s backs, etc. I said “actors” deliberately, because characterization is destroyed by all this messing around.

I can’t believe the scenes of this nature were scripted, because you wouldn’t deliberately set out to write such antidialogue. Nor do I believe that Gazzara, Falk and Cassavetes (fine actors all) could have acted these scenes so awkwardly if they were working from scripts; what we see are not performances, but the human beings themselves, photographed while trying not very successfully to improvise.

There are other things wrong with “Husbands,” but the script (or non-script) problem runs throughout the movie, undercutting a lot of potentially better scenes. There are some good scenes, even so. And some good ones that become unbearable because they run on so long. And there is always the presence of Cassavetes, who, whatever else his sins, doesn’t protect himself from the consequences of his inspirations.