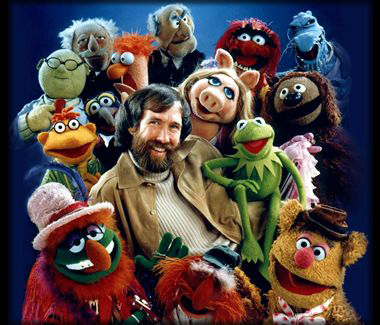

This is a book excerpt from Make Art Make Money: Lessons from Jim Henson on Fueling Your Creative Career by Elizabeth Hyde Stevens, now available in stores and online.

Tales of Jim Henson’s workaholism have a John-Henry quality to them.

He once had surgery during his lunch hour and continued to shoot until eight p.m.

Fran Brill:

I remember once on the set I saw Jim’s back was wounded. I said, ‘Jim, you’re bleeding from the back,’ and he said, ‘It’s no big deal.’

I remember Jim – he had walking pneumonia, and we were shooting a commercial outside in a gas station 30 years ago, and it was five degrees, and he should have gone to the hospital, and he was still working.

I just can’t believe his capacity for work. For instance, he would finish shooting for the week on “Labyrinth” in London, catch an airplane to New York, work on a new production, TV series, or whatever over the weekend, then catch a plane back to London Sunday night, and be at the studios early Monday morning to resume filming.

Caroll Spinney:

He could get by on an hour or two [of sleep]. Once in London we left a party with him at 2:00 A.M. I was concerned about a nine o’clock call time that morning. Jim said that he’d be ready for it because he had a 5:00 A.M. meeting with Robert Altman first.

Henson asked Spinney when he hired him:

When I work with Frank Oz, we’ll get into a project and work all day, all night, all the next day, and sometimes the next night two. Do you like to work like that?

During his years with Henson, Frank Oz described himself as “a worker,” “a drone”:

Going to work at 9 a.m. and getting back home at 9:30 at night, with time to eat, do some laundry and go to sleep.

On Henson’s lunch breaks from “The Muppet Show,” he would eat, conduct a writers meeting, and field business calls. When he took a cruise on the QE2 with his wife, he took the whole company with him to work in London. On his 29th birthday, he wrote a script for “Alexander the Grape,” an unpaid project. The work was his cake and streamers. The work was his gift to

himself. Henson turned forty on a plane trip and spent fifty on a “vacation cruise” with his agent. Jerry Juhl said, “Year after year, we watched him push himself beyond what we could possibly imagine. You had to try to keep up.”

Henson himself denied being a workaholic. “I work a great deal,” he said, “but I enjoy it.” Frank Oz has said, “It’s hard for people to understand the reason Jim worked so hard is he loved it.” This seems like a genuine sentiment, but what does it mean? What do you call someone who works all the time but is not a workaholic? And how would you ever distinguish one from a

workaholic?

Henson said, “Perhaps one thing that has helped me in achieving my goals is that I sincerely believe in what I do, and get pleasure from it. I feel very fortunate because I can do what I love to do.” Now, that sounds very nice to most people. Most of us want that. But not at the cost of what workaholism really entails. Do you really want to work nonstop for the rest of your life?

For one thing, it takes a toll on family life. During Jane Henson’s eulogy for her husband, she let slip a glimpse from the perspective of the famous man’s family:

Mostly, I just think now that it’s only us, his family. These are only his kids, I’m only his wife. They had messy rooms, I burned the dinner. He didn’t come home. The dog died. Whatever…all this stuff. It’s only us.

As Michael Davis wrote in Street Gang, “Jane was left abandoned in the suburbs while Jim Henson circumnavigated the globe.” In the boom period of 1980, The Saturday Evening Post said “Their marriage is one of show business’ more solid unions despite Jim Henson’s absence from their Bedford Hills, New York, home for up to six months a year.” The Hensons officially separated in 1987.

Walt Disney’s wife once described herself to a Time reporter as a “mouse widow.” In this sense, there were surely Muppet widows and orphans. His son Brian said the children visited Henson at work often:

He always had such a ball when he was at work, and that was one reason why we would love to go and visit him. And also, we were always welcome at work. No matter how young we were, we would hang around the shooting studio, and then the workshop, and even go to meetings and stuff, and be playing in the corner, and he was always fine with that.

One could imagine that another reason to visit Henson at work was that he was always there. A 1999 CNN profile compared interviews on the subject:

Cheryl Henson: When we were growing up, we weren’t very aware of my father being famous. That – there was much more of a sense that he was always more involved in his work, and he loved what he did, and always brought us into what he was doing.

Brian Henson: …He was also a very gentle and caring father. I remember even when he would work, sort of, endless hours, he’d pretty much always come home every night at some point to, like, tuck us in.

Jane Henson: Whether or not he came home every night to tuck them in, I don’t know. He certainly enjoyed being with them when he could. If they remember it as every night, that’s nice, isn’t it? I don’t think it was every night.

Henson clearly loved his family. Brian remembered him carving a turkey using the same voice he would later use for Link Hogthrob. In his Red Book journal, family trips are often accompanied by the word “lovely.” In the early days Jane would puppeteer with a bassinet next to her. In July of one year, Henson had the whole month to spend on an out-west trip with the kids visiting Muppets writer Jerry Juhl. Henson clearly raised five well-adjusted children.

But it’s not exactly the American dream – with picket fences or even simple cohabitation. This is not the work-life balance I’d want, ideally. I wouldn’t want my husband to be a Henson, or to have to be that husband. It seems at the very least difficult to keep a family together in this line of work, and it seems to work best when the family joins in.

In Henson’s TV movie “Emmet Otter’s Jug Band Christmas,” Emmet and his Ma both give up their family stability for the dream of making music. Ma “hawks” Emmet’s tool chest that he uses to do “odd jobs” to buy dress fabric so she will look good singing on stage. Emmet takes Ma’s wash-tub that she uses to do laundry and puts a hole in it, turning it into an upright bass. They both believe they can win the talent contest, and once they do, they’ll buy a gift for the other – a piano and a guitar. Both believe that music will save the family and provide for it.

Ma’s friend points out the jeopardy she’s putting her son in by her dream. “What if you don’t win, Alice?” Ma shoots back without a beat: “Got to win. Why, Emmet’s got to have a new guitar this Christmas.” After the initial O. Henry tragedy, though, there is a touching victory. By performing together, Ma, Emmett, and his friends get a job at the hotel inn. The pay is “regular” and Ma says, “I sure enjoyed my first night’s work.”

Imagine that, enjoying one’s work. But to get that, they had to give up stability of the other kind of work. For artists, like entrepreneurs, it seems, it’s all or nothing – frequently poverty or riches – but a traditional middle-class life it’s not.

This may look like sacrifice, and maybe it is, but remember what Henson said:

I sincerely believe in what I do, and get pleasure from it. I feel very fortunate because I can do what I love to do.

The thing that makes sacrifice worthwhile is that you believe in it. Walt Disney once said that a certain spirit prevailed at his studio. “I can see it in the guys,” he said, “They have a feeling that it isn’t a racket.