Who could have predicted that “Lethal Weapon” would turn out to be one of the most influential films ever made?

The film’s writer, Shane Black, probably guessed. He never lacked confidence. The original draft of “Lethal Weapon” included smart-alecky asides, like a description of a cliffside mansion as “the kind of house I’ll buy when this movie is a huge hit.” It was, and the result turbocharged the buddy action formula that powered a string of box office hits, from “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” and “Uptown Saturday Night” through “48 HRS” and “Running Scared.” Mel Gibson’s long-haired, widowed, suicidal loner cop Martin Riggs gets partnered with Danny Glover’s older, wiser, more measured family man Roger Murtaugh. Although they start out hating each other, by the end each man has gained a new friend, and the once isolated Riggs is welcomed into the Murtaugh family.

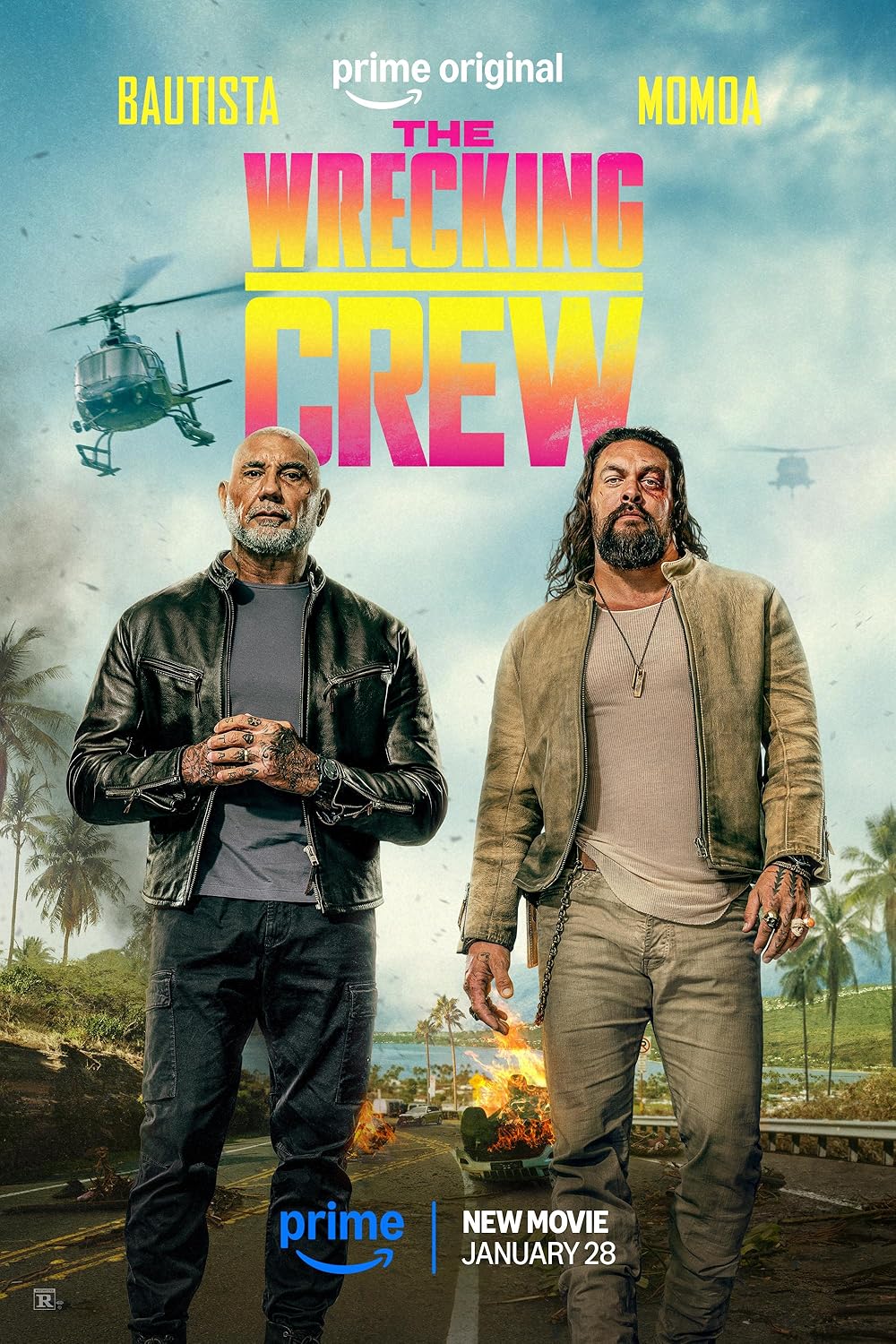

The Prime Video movie “The Wrecking Crew” is another entry in that vein, complete with story beats familiar from Black’s first produced script (especially in the final half-hour) and an overall Blackesque vibe, especially in the dialogue. Dave Bautista plays the rock-solid family man, James Hale, a former Navy SEAL turned drill instructor who has a house near Honolulu, a beautiful and charming child psychologist wife, Leila (Roimata Fox), and two adorable kids. Jason Momoa plays the loose cannon partner, James’ half-brother Jonny, a long-haired, hard-drinking, impetuous cop on an Oklahoma reservation who is introduced getting dumped by his long-neglected girlfriend Valentina (Morena Baccarin) on her birthday. (When she asks Jonny if he knows what day it is, he pauses nervously, then guesses “Wednesday?”)

They’ve been estranged for more than 20 years. But when their father, Walter, a sleazy private eye, gets killed in a hit-and-run accident while working a case in Honolulu, Jonny swallows his pride and flies to Hawaii for the funeral, setting up the inevitable reconciliation, plus lots of skillfully choreographed, sometimes slyly funny action sequences.

It’s all sprinkled with banter, some of it openly hostile, some profane and teasing but affectionate deep down, like stuff brothers would say to each other while roughhousing. Of course, the mystery turns out to be one more variant of “Chinatown,” involving a very sketchy real estate deal/land theft and intimations of a conspiracy that goes right to the top. Temuera Morrison plays Hawaii’s fictional governor, Peter Mahoe, who, of course, is part of the conspiracy. A governor doesn’t show up at the funeral of a bottom-feeding private detective that even his sons loathed unless he’s connected to the main story and the family guiding us through it.

Claes Bang plays real estate mogul Marcus Robichaux, an heir to a sugar fortune who hopes to get even richer from his crimes. Naturally, there’s a small army of security guys and henchmen for the brothers to punch, shoot, stab, and incinerate—a mix of city-roaming Yakuza foot soldiers (a band of whom attacked Jonny in Oklahoma, demanding a thumb drive his dad supposedly sent him) and a squad of gym-burly Caucasian dudes with quasi-military haircuts. And yes, there’s weird, repulsive, deranged chief henchman, Nakamura (Miyavi), a reptilian dandy who snorts cocaine off a drink tray at one of Robichaux’s glammed-out parties, then taunts James, who is posing as a caterer, right to his face.

What makes “The Wrecking Crew” worth seeing is what the cast and filmmakers do with the material. Simply put, this movie is better than its synopsis suggests, though not good enough to entirely overcome the familiarity of the component parts and the alternately jokey and sentimental tone (which is harder to pull off than studio executives seem to think). More so than “Lethal Weapon,” this evokes two less successful yet still much-loved Shane Black movies, “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” and “The Nice Guys.” Some of the action is ludicrous, but most of it is modestly scaled. And the characters are written and performed in a way that makes them recognizably human, even though the Hale brothers are, to quote Stephen Root‘s cop character, “two guys who look like they eat steroid pancakes for breakfast.”

Momoa and Bautista are two of the best actors to become movie stars by passing through the superhero factory, and they get a chance to prove it here, while still delivering what most viewers will expect: chases, shootouts, explosions, frat-house insults, moments of manly vulnerability, and a scene where the brothers get into a huge brawl. They’re convincing as the squared away but tightly wound older brother with a stable home life and the flamboyantly self-destructive younger brother whose adulthood has been warped by rage at what happened to them in youth. The brothers’ hellish childhood encompassed the murder of Jonny’s mother; Jonny’s awkward absorption by the Hale family; Walter’s chronic infidelity, which resulted in Jonny’s birth; and unstated but implied domestic abuse. Jonny has PTSD for sure, and it seems a safe bet that James has it, too.

It’s an indicator of the movie’s specialness that the most impressive scene isn’t the brother-on-brother street fight in pouring rain, but the aftermath when they sit together on the pavement, bruised and bloody, and talk about the sources of their hurt. Runner-up is the moment when the brothers embrace at the end of their mission, beaten and spent, and the mask of adulthood falls away, revealing the scared little boy who needed more love than he got and the older brother who failed to provide it.

Jonathan Tropper, who adapted “This is Where I Leave You” and co-created the action series “Banshee” and “Warrior,” wrote the script, which has more nuance and depth than you’d expect in a movie where trucks and cars fly through the air before exploding. It has a binding theme, forgiveness, and is filled with journalistic details of modern Hawaiian culture, locating the initial killing in a Honolulu neighborhood where such things have happened in real life; sending the brothers to the Hawaiian Home Land, which is stewarded under the Aha Moku system of resource management; reserving soundtrack slots for Indigenous music (like Ka’Ikena’s “Brains”); and peppering conversations with local idioms and slang. Jonny calls another character a squid, out-of-state speculators are referred to as “haole,” and the family name Hale is pronounced “HALL-ay” and translates as “home.”

Indeed, the entire movie is a tribute to the specifics of distinct cultures and the richness of a society that brings them together, while acknowledging that the fusion was forced by colonialism and crony capitalism, and that the conquered have justified resentments over that. The cast is filled with actual Hawaiians, especially Indigenous actors, including Momoa, who is half Native Hawaiian. (Bautista is Greek-Filipino, but should be admitted under the Pacino as Latino Act of 1983) Even Baccarin gets to honor her roots; half-Brazilian, she briefly speaks Portuguese, setting up another good joke on Jonny.

Director Angel Manuel Soto, who came to Hollywood by way of San Juan, Puerto Rico, has made three films in a row (“Charm City Kings,” “Blue Beetle,” and this one) that are culturally specific within genres that haven’t traditionally been welcoming to people like him. He’s good at everything the movie requires, including quiet moments of character development that you don’t normally find here. Although it looks backward to previous Hollywood hits, in all the ways that count, this movie is the future.