There are important messages embedded in “Seeds,” mostly around how Black farmers have been mistreated by this country (even by Democratic politicians like Joe Biden and Raphael Warnock, who made unkept promises to get their votes). But the most effective imagery is the simplest. Two come to mind: A girl sits in the back of a truck, driving with her great-grandfather to his next destination; the imagery is so powerfully relatable that you can feel the rumble of the truck bed, the wind on her face, and even the smell of the natural world around her. The second has similar power, as the same driver sings a lullaby to a crying baby to help it sleep. These moments have a tactile intimacy that’s incredibly powerful, placing these ordinary people in an almost timeless continuum of seemingly ordinary behavior that becomes extraordinary in memory, or through the eyes of a camera.

Director Brittany Shyne weaves together three stories of Black farmers in the South, lingering in these quiet moments to tie her subjects to the land, to family, and to history. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of farming in America, especially by Black landowners, knows that it’s not an easy time for these people, even though most would agree they’re the backbone of the country. People love to talk about supporting local farmers, including politicians, but the economy of mass production keeps pushing them to an unsustainable fringe. As Willie Head Jr. says, while trying to encourage a local religious leader to preach the value of farming to his congregation, there were 16.5 million acres of land owned by Black farmers in 1910; there are now 1.5 million acres.

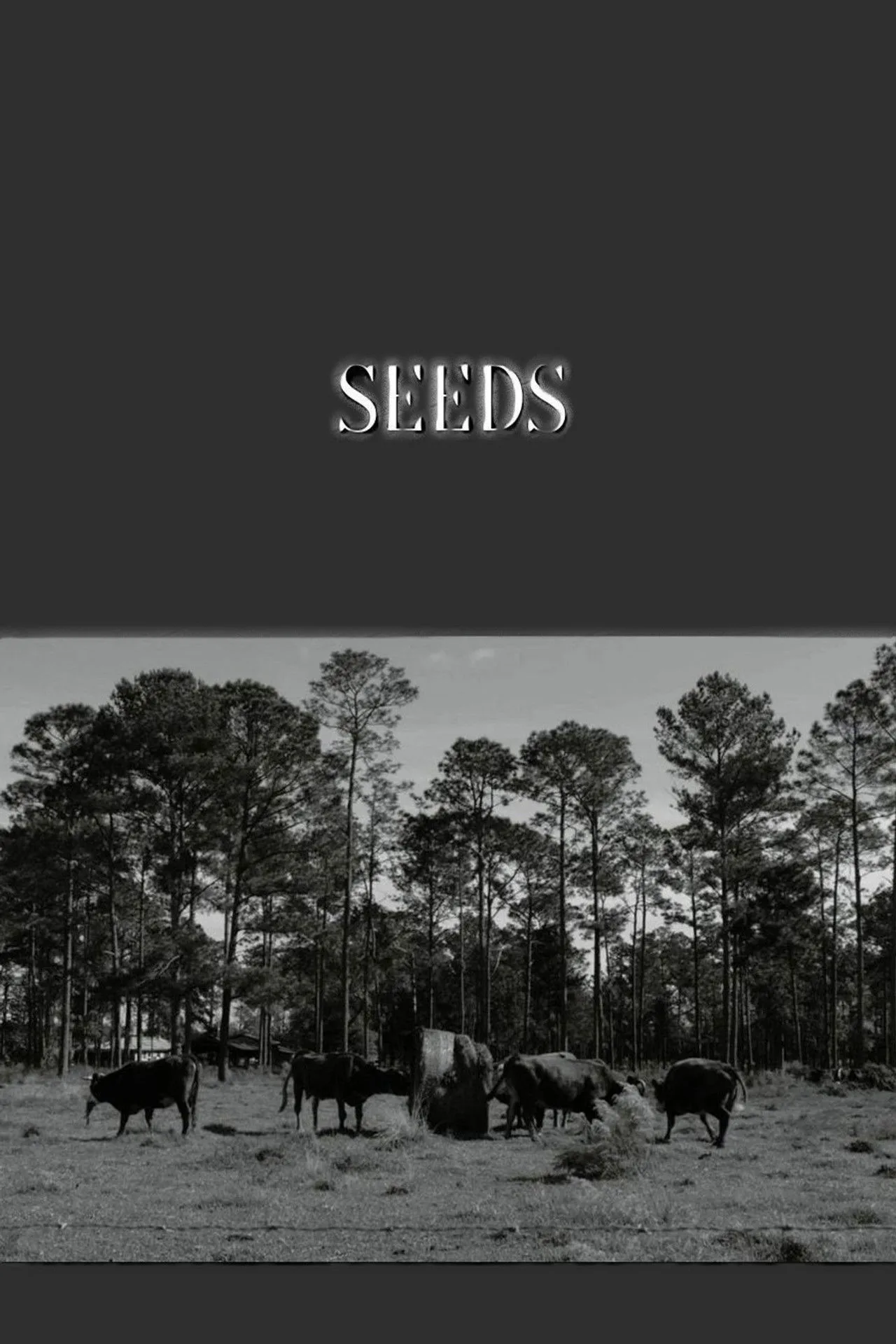

Head comes alive in this scene and others in which he’s actively fighting politicians who drag their feet—one of whom even says that the reason white farmers get action more quickly is that they’re more likely to sue—but the majority of “Seeds” consists of day-to-day activities that might be considered mundane by casual viewers. Shot by Shyne, who also receives cinematographer credit on the film, these moments attain a gentle grace through their accumulation and the temporal displacement caused by filming in black-and-white. While the aforementioned political backdrop makes the when of “Seeds” painfully clear, the aesthetic detaches it from a specific time and place, as these men and women go about their daily lives, which have looked like this for generations.

It doesn’t seem coincidental that Shyne focuses on people who have been a part of this world since before World War II. Of course, these veterans of the world of Black farming are going to have the most insight, but the talk of aging, the discussion of health issues among friends, just the creaking bones on display—these things give “Seeds” a sense of mortality, a feeling of something that’s about to be lost in this country, something that’s been taken for granted.

There’s history in the face of Carlie Cokrell, who has worked a farm owned by his family since the late nineteenth century. Carlie himself worked the land in the 1930s and is now approaching his nineties. We also meet his sister Clara, who also has that kind of connection to the farm. You can see a vital chapter of this troubled country on these faces, history that’s being lost, a history that’s in the air in this region. You can feel it in the wind that blows on your face.