In 1977, Tony Kiritsis fell behind on mortgage payments for an Indianapolis, Indiana, property that he hoped to develop into an affordable shopping center for independent merchants. He asked his mortgage broker for more time but was denied. This enraged Tony because he suspected the broker and his father, who owned the company, of conspiring to defraud him by letting the land go into foreclosure and buying it for much less than its market value. Tony showed up at the offices of the mortgage company, Meridian, for a scheduled appointment with his broker Richard O. Hall and took him hostage, demanding a settlement for his trouble and a public apology by his father. Tony carried a long cardboard box containing a shotgun with a so-called dead man’s wire, which he affixed to Hall as a precaution against police interference: if either of them were shot at, tackled, or even made to stumble, the wire would pull the trigger, blowing Hall’s head off.

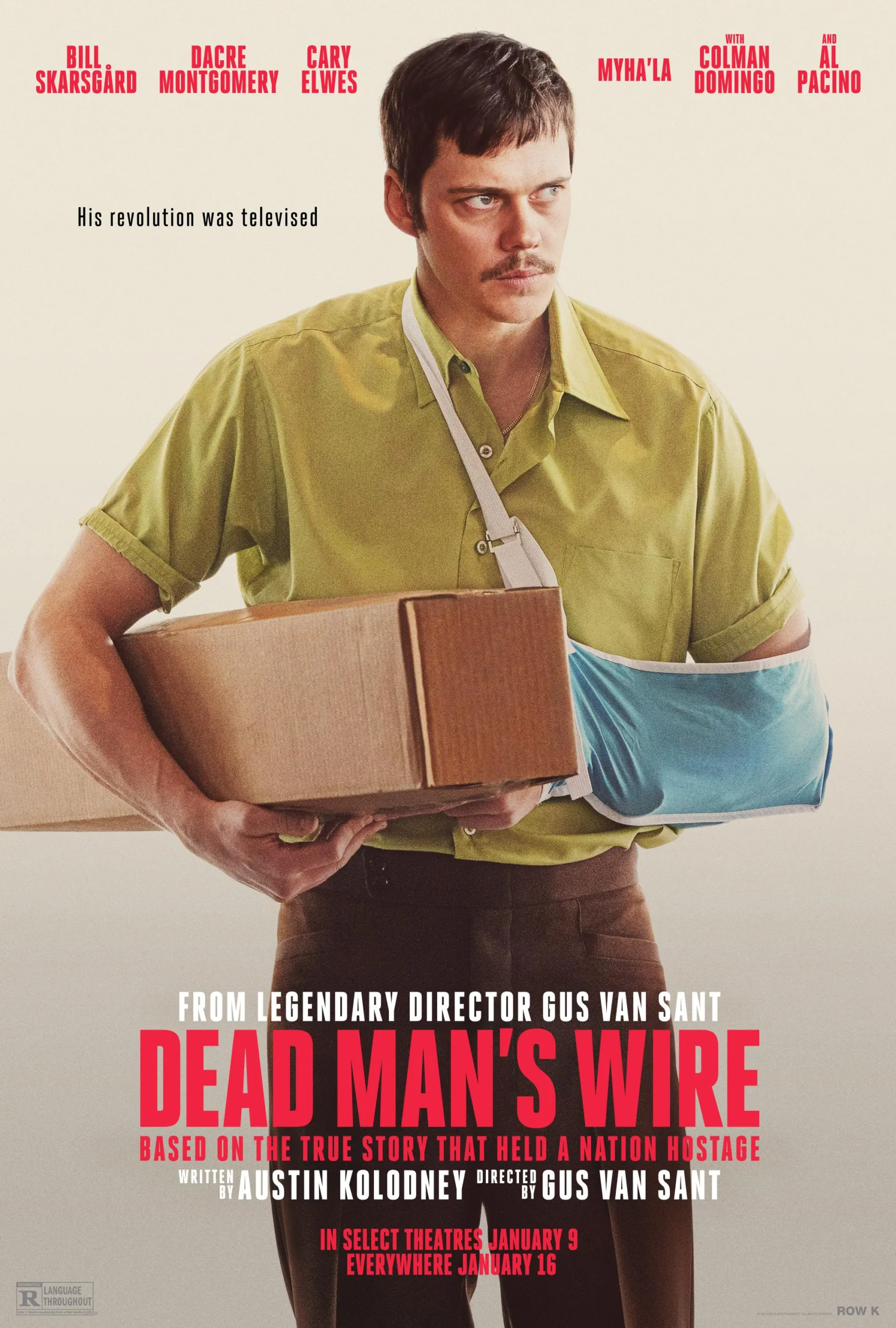

That’s only the beginning of a story that has inspired many retellings, including a memoir by Hall, a 2018 documentary and a podcast starring Jon Hamm as Tony Kiritsis. And now it’s the best current movie you likely haven’t heard about—from director Gus Van Sant (“Good Will Hunting”), starring Bill Skarsgård as Tony Kiritsis and Dacre Montgomery as Richard Hall. It’s unabashedly inspired by the best crime dramas from the 1970s, including “Dog Day Afternoon,” “The Sugarland Express,” “Network,” and “Badlands,” and can stand proudly alongside them.

From the pre-heist prep montage scored with Deodato’s groovy disco version of “Thus Spake Zarathustra” being played on the radio by philosophical DJ Fred Temple (Colman Domingo); through the expansive middle section, which establishes Tony as part of a thriving community that will see him as their representative in the war of labor and capital; through the ending and postscript, which leave you unsure how to feel about what you’ve seen but eager to discuss it, “Dead Man’s Wire” is a nostalgia trip of the best kind. Rather than superficially imitate the style of a specific type of ’70s drama, Van Sant and his collaborators connect with the essence of what made them powerful and memorable: their connection to issues that weighed on viewers’ minds fifty years ago and that have grown heavier since.

Tony is far from a criminal genius or a potential folk hero, but thinks he’s both. The shotgun box with a weird bulge, barely held together with packing tape, is a correlative of the mentality of the man who carries it. His home is filled with counterculture-adjacent books, but he’s a slob who loudly gripes during a brief car ride that his “shorts have been ridin’ up since Market Street,” and has a vanity license plate that reads “TOPLESS.” His eloquence runs the gamut from Everyman wisdom to self-canceling nonsense slathered in profanity . He accurately sums up the mortgage company’s practices as “a private equity trap” (a phrase that looks ahead to the 2008 financial collapse, which was sparked by predatory lending on subprime mortgages) and hopes that his extreme actions will generate “some goddamn catharsis” for himself and his fellow citizens, and “some genuine guilt” among Indianapolis’ lending class.

He’s also intoxicated by sudden fame. The hostage situation migrates from the mortgage company to Tony’s shabby apartment complex, which is quickly encircled by beat cops, tactical officers, and reporters (whose ranks include Myha’La as Linda Page, a twenty-something, Black local TV correspondent looking to move up). Tony also forces his way into the life of Temple, one of his heroes. Temple tapes his first phone conversation with Tony, previews it for police, then grudgingly accepts their “request” to continue the dialog, and plays tapes of their talks on his morning show. (Temple is based on Fred Heckman, the news director of Indianapolis radio station WIBC-AM whom the real Tony Kiritsis said was the only journalist he trusted to tell his story. Changing the reporter to a DJ closes off some avenues of inquiry into journalistic ethics; but it also opens the movie up culturally, and allows for a seamless blend of images, monologues and music in the spirit of “Do the Right Thing,” in which a community radio host doubles as narrator.)

Despite the avenues for redress that he’s been offered, Tony can’t stop his inner petty schmuck from erupting and messing things up. He vacillates between treating Hall as a cardboard representative of the financial elite (when Hall, Sr. finally agrees to speak with Tony via phone from a tropical vacation, Tony sneers to Hall the younger, “Your daddy’s on the line—he wants to know when you’ll be home for supper!”) and connecting with him on a human level. When he’s not bombastic, he’s needy and fawning. “I like you!” Tony keeps telling Fred—as if a Black man who’d built a comfortable life for himself and his wife in 1977 Indiana could say No when representatives of an overwhelmingly white police force drafted him.

Ultimately, however, making perfect sense and effecting lasting change are no higher on Tony’s agenda than they were for the protagonists of “Dog Day Afternoon” and “Network.” Like Tony, these are unhinged audience surrogates whose media stardom turns them into human megaphones for anger at the miserable state of things, and radicalizes them against the institutions that worsen it. In “Dead Man’s Wire,” those institutions include local cops who—in the words of “Dog Day Afternoon” bank robber Sonny Wirtzik—wanna kill Tony so bad that they can taste it. The discussions between Indianapolis police brass and the FBI (represented by Neil Mulac’s Agent Patrick Mullaney, a straight-outta-Quantico robot) are mainly about how to set up the kill.

The aforementioned phone call from Richard Hall, Sr., who had previously sent a vice president to apologize to Tony on his behalf, evokes a key moment in another spectacular ’70s case, the kidnapping of John Paul Getty III: when hostage-takers called their victim’s wealthy grandfather, they found out that he would rather lose a grandson than part part with money. The elder Hall is concerned but not panicked. It becomes sickeningly clear that he views his own flesh-and-blood as another asset he can write off. This horrible man is played by “Dog Day Afternoon” star Al Pacino—inspired casting that not only officially links Tony to Sonny Wirtzik but proves that, at 85, Pacino can still bring the heat.

With his frizzy grey toupee, self-satisfied Midwest twang, and punchable smirk, the onetime ‘7os superstar is skin-crawlingly perfect as an old man who built a fortune on being good at one thing and thinks it makes him an expert on all things, including the conduct of Real Men holding the line against women and sissies who’ve rebranded weakness as vulnerability. After watching coverage of Tony getting emotional while keeping his shotgun trained on Richard, Jr., he beams with pride that Tony shed tears but his own son did not. (Kelly Lynch, who costarred in another classic Van Sant film about American losers, “Drugstore Cowboy,” plays Richard, Sr.’s trophy wife, who is visibly uncomfortable with her husband’s monstrousness but won’t say a word against him.)

Van Sant was 25 during the real-life incidents that inspired this movie. That might partly account for the physical realism of the production, which does not feel created but simply observed, in the manner of ’70s movies whose authenticity was strengthened by letting dialogue overlap and compete with environmental sounds; shooting mainly in pre-existing locations, and putting the actors in clothes that looked like they’d been hanging in closets for years. Peggy Schnitzer did the costumes here, Stefan Dechant the production design, and Arnaud Poiter the cinematography, presumably while wearing gold chains, bell-bottom pants and platform shoes. The soundscape was overseen by Leslie Schatz, who keeps the environments believably busy while making sure the important bits are understood. It should also be mentioned that the film’s blueprint is an original screenplay by a first-timer with working class credentials: Adam Kolodny, who wrote it while working as a custodian at the Los Angeles Zoo.

More impressive than the film’s behind-the-scenes pedigree is its vision of another time that comes to seem not that different from our one. It is both a lovingly constructed time machine highlighting details that now seem as antiquated as lithography and buckboard wagons (the film deserves a special Oscar just for its phones) and a wide-ranging consideration of indestructible realities of life in the United States. The latter are highlighted in such a way that you notice them without feeling as if the movie pointed them out.

For instance, consider Tony’s infatuation with Fred Temple, which peaks when Tony honors his hero’s influence by “soul dancing” for his hostage. What we see here is a pre-Internet version of what we now call a “parasocial relationship.” An awareness of racial dynamics is baked into it, and into the movie as a whole. Domingo’s performance as Temple captures the tightrope walk that Black celebrities have to pull off, reassuring their most excitable white fans that they understand and care about them without cosigning condescension or behavior that could escalate into harassment. Consider, too, the matter-of-fact presentation of how easy it is for violence-prone people to buddy up to law enforcement officers, especially when they inhabit the same spaces. When Indianapolis police detective Will Grable (Cary Elwes), Tony’s designated executioner, approaches him on a public street soon after the kidnapping, Tony exclaims, “Hi Mike! Nice to see you!”

And then, of course, there’s the economic and political framework, which is built with a firm yet delicate hand, and compassion for the vibrant messiness of life. “Dead Man’s Wire” depicts an analog era in which crises like this were treated as important local matters that involved local people, businesses, and government agents, rather than fuel for a global agitprop industry posing as a news media and a parasitic army of self-proclaimed influencers. The filmmaking insists on the uniqueness and value of every life it shows onscreen, however briefly, from the unnamed citizens silently watching news coverage of the crisis on TVs at their workplaces to minor characters like Fred Temple’s excitable Asian-American coworker (Vinh Nguyen), who scouts unknown bands by listening to demos on NAB Cartridges in a closet-sized office filled with pot smoke.

All this is drawn together by Van Sant and editor Saar Klein in pop music-driven montages that show how every member of the community depicted in this tale is connected, even if they don’t know it or refuse to admit it. As John Donne put it, “No man is an island/Entire of itself/Each is a piece of the continent/A part of the main.” The struggle of the individual is summed up in one of Temple’s sign-off lines: “Let’s remember to become the ocean, not disappear into it.”