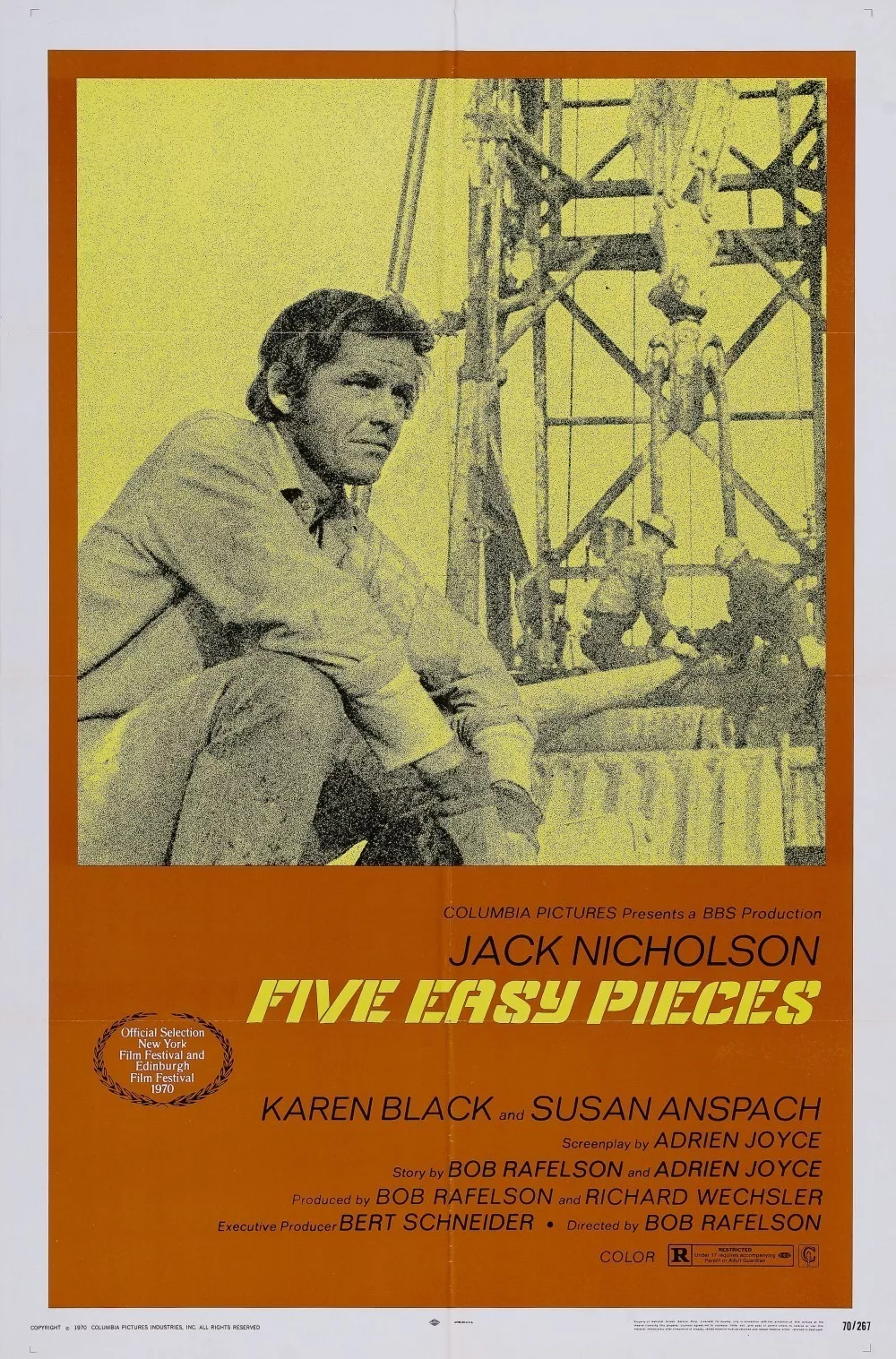

“Easy Rider” proved in 1969 that Jack Nicholson was a great character actor. “Five Easy Pieces” proved in 1970 that he was a great actor and a star. This is the film, more than 10 years into his career, where he flowered as a screen presence, as Jack the lad, the outsider, capable of anger, sarcasm, self-pity, also capable of tenderness and grief, ready for violence but not very good at it. There were glimpses of this persona in earlier films (see his character poet in “Hell's Angels on Wheels” in 1967), but now here was a film of uncommon depth and originality, a canvas for a man named Robert Eroica Dupea, his middle name inspired by Beethoven’s Third Symphony.

It is difficult to explain today how much Bobby Dupea meant to the film’s first audiences. I was at the New York Film Festival for the premiere of “Five Easy Pieces,” and I remember the explosive laughter, the deep silences, the stunned attention as the final shot seemed to continue forever, and then the ovation.

We’d had a revelation. This was the direction American movies should take: Into idiosyncratic characters, into dialogue with an ear for the vulgar and the literate, into a plot free to surprise us about the characters, into an existential ending not required to be happy. “Five Easy Pieces” was a fusion of the personal cinema of John Cassavetes and the new indie movement that was tentatively emerging. It was, you could say, the first Sundance film.

Nicholson was not the film’s only discovery. There were quirky supporting roles for Karen Black, Lois Smith and Ralph Waite, all pitch-perfect, all relatively new to movies. It established Bob Rafelson, the director and co-writer, as a leader of the American New Wave. Its cinematography was by Laszlo Kovacs, a Hungarian who’d also shot “Easy Rider” and “Hell’s Angels on Wheels,” and became one of the best of all cameraman. The film’s greatest influence came through the screenplay, by Rafelson and Carole Eastman; it allowed detours and digressions, cared more about behavior than plot, ended in a way and tone that could not have been guessed from its beginning.

And it had moments that passed permanently into the collective memory of moviegoers. The most famous of those is always referred to as the Chicken Salad Scene (see sidebar). Is there a movie lover who cannot quote it? That speech, and the shot of Nicholson in a football helmet on the back of a motorcycle in “Easy Rider,” are the defining moments in his sudden transition from anonymity to legend.

The movie has other memorable lines (“I faked a little Chopin, and you faked a big response”), but what it has above all is Bobby Dupea: He’s a voluntary outcast who can’t return to his early life, yet has no plausible way to move forward. He’s stranded between occupations, personas, ambitions, social classes. In 1970 (and before and since), most American movies centered on heroes who defined the plot, occupied it, made it happen. “Five Easy Pieces” is about a character who doesn’t fit in the movie. There’s not a scene where he’s comfortable with the people around him, not a moment when he feels at home. The movie’s story traces a journey back through a life where Bobby (in his own view) disappointed people, could not be counted on, misbehaved, underachieved. The only person in the movie who openly criticizes him is the one who knows him the least; his family and his waitress girlfriend overlook or forgive his flaws, but he can’t forgive himself.

The first half of the film, set in the oil fields of California, gives no hint of the second. Bobby is an oil-well rigger who lives with Rayette Dipesto (Karen Black), a waitress with big hair, frosted lips and a worship of Tammy Wynette. She’s pathetic in her hunger for him, her fear of losing him. When she learns that she’s pregnant, Bobby only finds out from his buddy Elton (Billy “Green” Bush), a rigger with a high laugh and down-home seriousness. When Elton lectures him on the joy of family life,, we get the first glimpse of Bobby’s concealed idea of himself: “It’s ridiculous. I’m sitting here listening to some cracker a——, lives in a trailer park, compare his life to mine.” But at that point we think of Bobby as a cracker, too. Who is he?

The action moves easily through the blue collar world of Billy and Rayette. They have a fight and make up. They go bowling with Elton and his wife. Bobby gets to hold their baby, and we see his discomfort around children–he’s not ready for the responsibility, or even the thought, of a child.

Afraid of commitment to Rayette, Bobby has sex with Betty (Sally Struthers), a pick-up. They are wild, abandoned; Betty screams in delight and Bobby loses himself in sex, carrying Betty around the room, finally ending exhausted. Then we can read the motorcycle logo on his T-shirt: TRIUMPH. That gets a laugh, to mask the sadness of the scene. Betty isn’t what he’s looking for, either.

Earlier, there’s a preview of the hidden Bobby. Caught in a traffic jam, he sees a piano on the back of a moving truck, climbs aboard and plays as the truck pulls away. His style is frantic, angry, loud, fast; he wants to hurt the music. We didn’t even know he could play. Later, in an abrupt transition, he walks into a recording studio, and we learn that the pianist is his sister Partita (Lois Smith). She loves him unconditionally, as we can tell by her smile and her manner; she tells him it’s time for him to come home, that their father has had a stroke. That opens the movie’s second half.

He will drive from California to an island off the Washington coast, where his family lives communally. He reluctantly brings along Rayette, then dumps her in a motel and goes for the first time in years to meet his father, Nicholas (William Challee); his brother, Carl Fidelio (Ralph Waite); Carl’s student and lover, Catherine (Susan Anspach), and the newest member of the household, the male nurse Spicer (John P. Ryan), who Partita has an eye for.

The father never speaks. Carl is friendly in a distant, jolly way that is critical by its very refusal to pass judgment. Bobby is attracted to Catherine, a musician of class and poise, and she has sex with him, but scoffs at the notion that they have a future: “You have no love for yourself, no love for family, for friends–how can you ask for love?” This visit produces many memorable scenes, two in particular. One involves Rayette’s surprise arrival by taxi, and her dumb-like-a-fox behavior as she works her redneck persona to let everyone know what she thinks of them. When an insufferable visiting mystic (Irene Dailey) tries to put her down, Rayette loudly tells Carl about a friend’s kitten “that got squashed flat as a tortilla outside their mobile home,” and we know exactly what she’s doing. When the woman tries to put her down, Bobby rises to Rayette’s defense: “You shouldn’t even be in the same room with her, you pompous celibate.”

Dialogue like that, and there is a lot of it, makes the movie alive with surprise and possibility. These characters are not limited to banalities that can easily be dubbed for the foreign release, but speak varieties of American vernacular from top to bottom of the social spectrum (sometimes switching their styles to fit an occasion–Bobby does a lot of that).

Listen to the other great scene, as Bobby wheels his father’s chair out to the shoreline and in a monologue tries to explain his life, cannot, and breaks down in tears. This scene, so wonderfully performed by Nicholson, is where the heart of the movie resides. This remorseful son, whose piano playing never pleased his father (“We both know I wasn’t very good at it”) is the Bobby that all the other Bobbys seek to conceal.

The last long scene, at the gas station, is the kind of ending the film deserves. It would not be allowed today, when happy endings are legislated by contract. It is true to the Bobby Dupea we have come to know. It shows him escaping from all of his lives, because he can’t face any of them.

“Five Easy Pieces” has the complexity, the nuance, the depth, of the best fiction. In involves us in these people, this time and place, and we care for them, even though they don’t request our affection or applause. We remember Bobby and Rayette, because they are so completely themselves, so stuck, so needy, so brave in their loneliness. Once you have seen movie characters who are alive, it’s harder to care about the robots in their puppet shows.