“Ghost in the Shell” is full of dazzling images that suggest a rich, profound narrative the film is never able to achieve. A young woman brutally rips the hatch off a tank. Her skin and bones crack, revealing mechanical sinew underneath her human exterior. Holographic advertisements the size of skyscrapers glitter across the city’s landscape. Surgeons wear uniforms the color of fresh blood. A robot fashioned in the form of a geisha bends her appendages, crawling up the wall like a frightened spider. These visual delights may provoke momentary awe but they have little impact.

Director Rupert Sanders and his collaborators aren’t married to recreating the influential manga or its 1995 anime adaptation wholesale. This isn’t inherently a problem. But how they choose to change this material is. They take the basic skeleton of the story and some its tantalizing imagery, but strip them of their power.

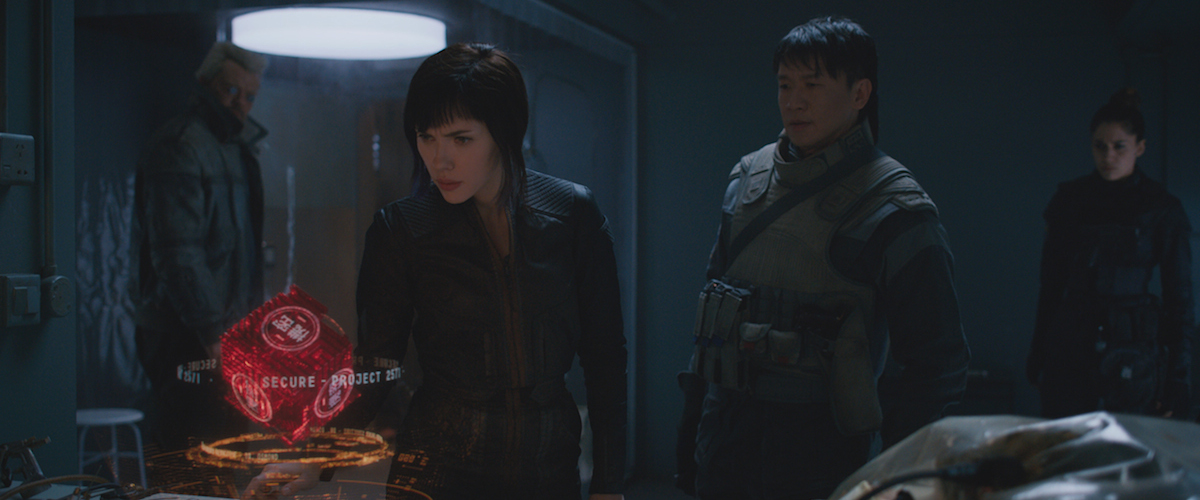

“Ghost in the Shell” takes place in a future in which cybernetic enhancement isn’t just routine but expected. Characters outfit themselves with tech that makes alcohol poisoning a thing of the past, gives them great abilities, and allows them to survive harrowing accidents that would have previously left them dead. The latter is the case for Major Mira (Scarlett Johansson). She was rescued in the wake of an attack on a refugee boat that left her so gravely injured that the government-funded Hanka Industries saves her by placing her mind into a completely artificial body. As characters repeat ad nauseam, she’s the first of her kind. The Major, as she’s routinely referred to, is the perfect blend of the organic and the synthetic, man and machine. She has the mind and soul (or “ghost”) of a human woman coupled with the astounding advantages of a machine form. Reborn in this new body, the Major works as an efficient if somewhat reckless agent for Section 9, an ill-defined anti-terrorism division led by Aramaki (Takeshi Kitano). But there’s something amiss beyond the Major’s poor understanding of her own humanity and place in the world. She’s having “glitches,” visual and auditory hallucinations, with increasing regularity, suggesting that her superiors are lying to her. Once the terrorist that Section 9 is hunting down, Kuze (a bored Michael Pitt), warns her not to trust Hanka Industries, the Major searches for the truth behind her existence.

“Ghost in the Shell” jettisons the complex preoccupations of the source material in order to traffic in a distinctly American story about heroic individualism. There’s also an interest in exploring corporate resistance, which is a bit hypocritical considering the behemoth behind this film, and that the narrative rests these problems on individuals rather than dissecting the systematic forces that make their actions possible. For this approach to the material to work, the characters and the world they inhabit need to feel distinct. Unfortunately, one of the most damning faults of this adaptation is that its world building, while having the appearance of intricacy, proves to be as hollow as the rest of the film upon closer examination.

The visual landscape of “Ghost in the Shell” suggests a host of fascinating questions. What does the chance of being hacked suggest about the quicksilver nature of identity in this world? If you don’t have cybernetic upgrades what does that mean for your life personally and professionally? The team members of Section 9 seem to be diverse—has technology affected the way people relate to their own race and gender? Unfortunately, these questions are only momentarily considered or blithely ignored in order to reiterate just how special the Major is, in case you forgot from the twenty other times characters mention it.

This lack of detailing extends to the characters themselves. The Major spends a considerable amount of time with her Section 9 teammates but I honestly couldn’t name one single personality trait for any of them beyond being dedicated to their work. The only one who gets enough focus to rise above being completely forgettable is Batou (Pilou Asbæk). He has a comfortable rapport with the Major that causes her to crack a smile and some occasional jokes, suggesting she has more humanity than she gives herself credit for. As Dr. Ouelet, the Major’s chief creator, Juliette Binoche imbues a warmth and nearly neurotic sense of overprotection that suggests an interesting mother/daughter dynamic. This isn’t enough. The lightning pace of the film means that just when a scene is about to touch a nerve it moves on to the next. The score buzzes and swells with intrigue that the action on-screen doesn’t communicate. Typically, a strong lead performance can make even the most cumbersome film have charm and merit, but Johansson struggles to create a meaningful emotional through line for the Major.

In recent years, Johansson has proven to be a mesmerizing actress who brings an intelligence and fearsome quality to her work. “Ghost in the Shell” is a continuation of the roles she’s excelled at playing in “Under the Skin,” “Her,” and various turns as super-spy Black Widow in Marvel’s Cinematic Universe. It marries her impressive physicality as an action star, emotional vulnerability, and steely determinism. Yet, even she isn’t skilled enough to imbue the Major with the depth necessary for her arc to feel moving and profound. She also can’t sell me on the ridiculous philosophy the film peddles about how memories are inconsequential to human identity; apparently, only our actions matter.

All these issues—poorly thought out moral quandaries, surface level world building, scant character development—come to a head in the film’s queasy racial politics. A dark cloud has hung over “Ghost in the Shell” since Johansson’s casting was announced. The debate over whether her character, who in the source material had the name Motoko Kusanagi, should reflect the racial origins of the manga and subsequent anime films was intelligently explored in an essay for The Verge by Emily Yoshida. No matter where you come down in the debate over this, it becomes hard to ignore when you notice how the most important characters are white or that every time Aramaki speaks Japanese the Major only replies in English. “Ghost in the Shell” makes the troubling decision to use Japanese culture, visual flourishes, and source material but decides that a Japanese actress as the lead would be a step too far. At times, “Ghost in the Shell” is beautiful, even stunning. But these visual pleasures can’t mask the narrative emptiness. Never has there been a film so obsessed with the human soul that proves soulless itself.