Is “Under the Skin,” in which Scarlett Johansson plays a mysterious woman luring men into a fatal mating dance, a brilliant science fiction movie—more of an “experience” than a traditional story, with plenty to say about gender roles, sexism and the power of lust? Is it a pretentious gloss on a very old story about men’s fear of women, and women’s discomfort with their own allure? Does it contain mysteries that can only be unpacked with repeat viewings, or is it a shallow film whose assured style and eerie tone make it seem deeper than it is? Is there, in fact, something beneath the movie’s skin? Why is every sentence in this paragraph a question?

I can answer that last one: “Under the Skin,” Jonathan Glazer’s first film since 2004’s “Birth,” is special because it’s hard to pin down. It doesn’t move or feel like most science fiction movies—like most movies, period. It’s a film out of its time. Its time, I think, is the 1970s, when directors like Alejandro Jodorowsky (“El Topo,” “The Holy Mountain”) and Nicolas Roeg (“Don't Look Now,” “The Man Who Fell to Earth“) made viscerally intense features with subjective visuals and sound effects and music and dissociative editing. Certain modern filmmakers still work in this mode occasionally—for instance, the Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, whose 1998 film “A Taste of Cherry” shares some odd similarities with “Under the Skin.” As you watch any of those films, you think about what they’re trying to say, or what they “mean,” or on a much simpler level, what the heck is happening from one minute to the next. But at a certain point you realize that on the simplest level, such films are saying: “Here is an experience that’s nothing like yours, and here are some images and sounds and situations that capture the essence of what the experience felt like; watch the movie for a couple of hours, and when it’s over, go home and think about what you saw and what it did to you.”

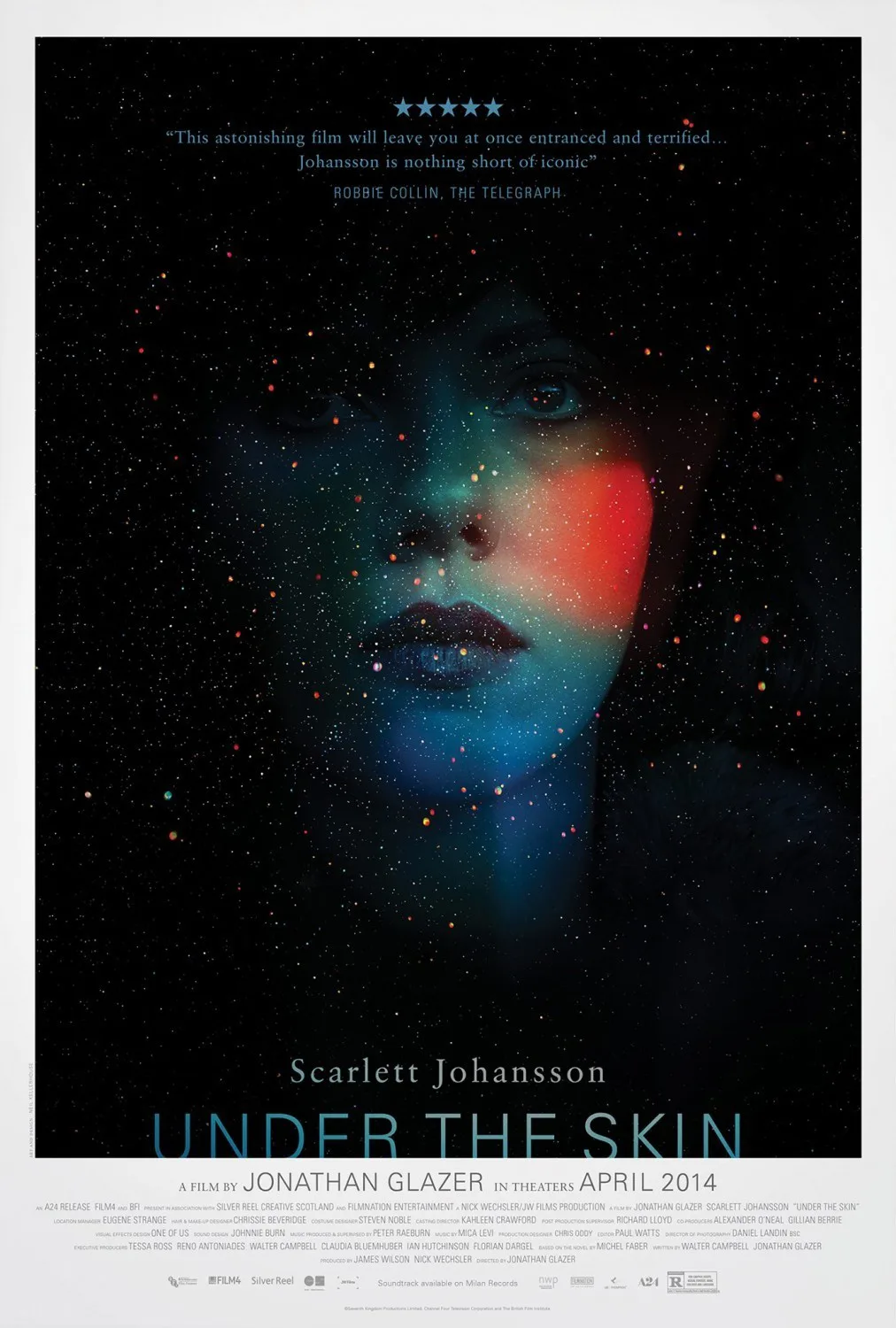

The opening of “Under the Skin” might remind you of the openings of “2001,” “Blade Runner” or “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” or certain movies by Paul Thomas Anderson: an immersive, hypnotic gambit that feels like the mental equivalent of a palate cleanser. As Mica Levi’s score buzzes like an otherworldly hornet’s nest, we see a black screen with a tiny white dot in the middle. The dot grows incrementally larger, or closer, before shaping itself into a pattern of rings that simultaneously suggests a birth canal dilating, the stages of a rocket separating, and a lunar eclipse as seen through a telescope’s lens. What’s happening? The movie doesn’t exactly tell us. Maybe this is the heroine, Johansson’s character, falling to earth, or landing on earth. Maybe. Then see a man on a motorcycle retrieving the body of a young woman (also Johansson) and the woman donning her body as one might don a set of clothes. Who is the motorcyclist? Is he her mate? Her procurer? Her handler? Who is she? An astronaut? The vanguard in an alien invasion? An intergalactic sex tourist visiting Earth as an American might visit Amsterdam or Bangkok? The opening is the first of many sequences in “Under the Skin” that feel more figurative than “real”—moments in which we suspect we’re seeing the poetic representation of a thing, not necessarily the thing itself.

Most of the movie does, however, feel “real,” particularly scenes of the woman driving around Glasgow, Scotland, enticing men to get into her white van and follow her to an abandoned flat where, it is implied, they have sex. The men (shot by hidden cameras in a series of improvisations) seem like real men. They aren’t movie star handsome. They’re young, alert and engaging. Some are funny and seem like they might even have a chance with an attractive young woman who was not an extraterrestrial looking for a hookup. The unnamed heroine seems genuinely intrigued by their banter, sometimes amused, never in a condescending way. She seems to be learning about this new environment and the people in it, and enjoying herself when she isn’t anxious about passing for human.

But once we join the woman and her men in the vacant apartment, the film turns figurative again. The men follow the heroine through a pitch black doorway that’s yet another symbolically charged portal; it’s as if, by stepping through it, both she and they are being born, or reborn. Once the couples step through, we don’t see any sex, just nudity plus movement, in what might be a musical number choreographed by performance artists. The frame is completely black except for the woman and her prey. They both take their clothes off, item by item. The woman always backs away from the man, slowly, confidently, but with an eerily blank expression (most of Johansson’s expressions are eerily blank, except when she’s unexpectedly laughing or showing confusion or fear). The man walks forward, but seems to trudge lower and lower into a black pool. The heroine, meanwhile, continues to walk backward on the pool’s undisturbed surface.

The leading lady gives a performance different from any you’ve seen from her. It’s keenly attuned to the movie’s aesthetic. It’s more about intuition and gesture than dialogue. Johansson has to be at once achingly specific and so general that you can hang symbols on her. She pulls it off. And somehow Johansson, Glazer and his cinematographer Daniel Landin transform how we think of this star. They’ve taken one of the most glamorous actresses of the modern era—a woman whose looks have been abstracted into hubba-hubba caricature in most films, and on awards shows—and ironically restored her earthliness by having her play a creature not of this earth. They’ve made her beautiful in a real way, with hips and blemishes and folds in her skin.

There are hints of an unspoken psychic bond between the woman driving around in the white van picking up men and the mysterious motorcyclist zipping around Glasgow, hugging the curves of hilly roads that dip and snake like the ones in the opening sequence of “The Shining“—but we never find out precisely what the connection is. There are times when the heroine is a vessel emptied of meaning. Other times she seems like a human struggling to learn the subtle everyday details of a new culture. She speaks in an English accent, the men in thick Scottish accents. The absence of subtitles adds to the feeling that she’s a stranger in a strange land, and makes us empathize with her as we try to understand the men. We study their facial expressions and gestures to plug gaps in meaning.

She’s the woman as Other, yet she’s also “just” a woman, or “just” an alien creature. She is everything and nothing. There are times when the film seems to be too freighted with meaning, as if inviting scholars to write thesis papers analyzing its masculine and feminine symbols. At other times it seems to be deliberately mocking such impulses, giving false clues to literal-minded viewers who insist on trying to “solve” movies like equations. But the film’s disturbing finale goes beyond such simplistic “this=that” analysis. First it removes all doubt as to who the heroine is—what her “secret” is. Then goes beyond such questions, so that you feel a mix of despair and wonder not unlike what you’d feel at the end of a melodrama, or a Grimm fairy tale whose ending, however dreadful, is not depressing because it feels right.

Movies like this don’t find their way into commercial cinemas very often. When they do, they don’t tend to star anyone you’ve heard of. When a film comes along that doesn’t fit the usual marketplace paradigms, such as “The Tree of Life” or “Upstream Color” or “Spring Breakers,” you take notice. “Under the Skin” is a film in that vein. Right after it ended, I argued its merits with a friend who didn’t care for it, and I jokingly referred to it as “what would happen if Michelangelo Antonioni directed ‘Species.'” It sounds like a glib joke, but I meant it as a compliment to the movie’s mix of horror film menace and intellectualized control. It seems to hard to believe today, now that the pantheon of great directors has hardened into consensus, but there was a time when people thought there was less to Antonioni than met the eye, too. On the basis of this film, “Birth” and his debut “Sexy Beast,” Glazer strikes me as a director in the same weight class as Antonioni and all the other great filmmakers I’ve name-dropped in this piece, including Kubrick, the artist Glazer most often evokes. (Like Kubrick, Glazer takes his time—this is only his third feature in 13 years—and like Kubrick, he becomes more formally audacious, technically innovative, and inscrutable with each new work.)

I wanted to watch “Under the Skin” more than once before I reviewed it. Life got in the way of that. No matter: I feel secure in saying that it’s going to end up on my list of the year’s best movies. I saw it almost a week ago and it has never been far from my mind. Is it perfect? Probably not. It might be too much of something, or too little of something else. Time will sort out the particulars. But I do know that the movie’s sensibility is as distinctive as any I’ve seen. “Under the Skin” is hideously beautiful. Its life force is overwhelming.