Sarah Palin lacked the preparation or temperament to be one heartbeat away from the presidency, but what she possessed in abundance was the ability to inflame political passions and energize the John McCain campaign with star quality. That much we already knew. What I didn’t expect to discover after viewing “Game Change,” a new HBO film about the 2008 McCain campaign, was how much sympathy I would feel for Palin, and even more for John McCain.

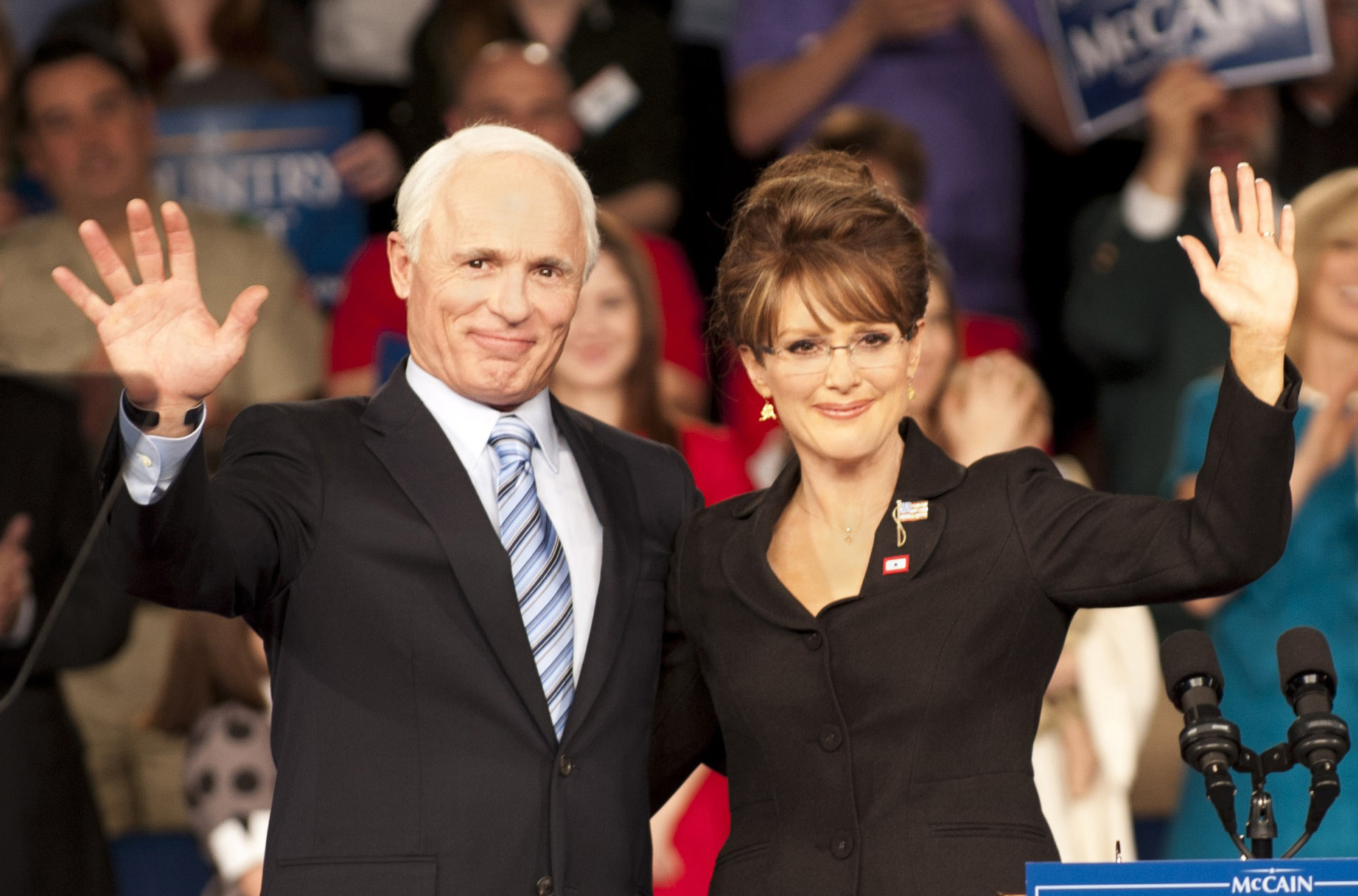

The movie is largely told from the point of view of two McCain advisers, Steve Schmidt (Woody Harrelson) and Nicolle Wallace (Sarah Paulson). Schmidt was instrumental in the selection of Palin (Julianne Moore) as the running mate of McCain (Ed Harris), and Wallace was another senior adviser. During the campaign, they share their concern as Palin reveals a comprehensive lack of knowledge about current events.

In the days before Palin’s selection, it seemed so much simpler. McCain’s inner circle shared a fear of Barack Obama as a formidable opponent. They had little enthusiasm for McCain’s preference for running mate, Sen. Joe Lieberman, a centrist independent from Connecticut. As they saw Obama drawing record-breaking crowds, Lieberman’s appeal seemed tepid. What McCain needed, they became convinced, was a “game changer,” a vice presidential candidate who would alter the landscape.

On paper, the governor of Alaska was ideal. In person, she had delightful charisma. It’s made clear in the film that Schmidt and his team did only a superficial background check on her, and later Schmidt was to berate himself for not asking her a single policy question. McCain, persuaded that she might be the game changer he needed, went along. Doubts began to form before the GOP convention, but they were swept away by her triumphant speech accepting the nomination. Backstage, the McCain troops hugged themselves with delight.

Watching that speech at home, I remember thinking, “Obama’s in real trouble.” Some GOP pundits confessed they had crushes on her. Palin’s crowd appeal was enormous. She went overnight from being an obscure governor to being a superstar. Then reality began to sink in: Palin knew virtually nothing about current events, world politics, history, geography. Wallace and Schmidt share their astonishment: She didn’t know what the Fed was. She thought Korea was one country. She believed Queen Elizabeth was the British head of state.

In preparation for her first debate with Democratic VP candidate Joe Biden, she hopelessly shuffled file cards and retained little. In an interview with Katie Couric of CBS, she came across as a deer caught in headlights. She had such an indifference to facts that she repeated the same errors (about the Bridge to Nowhere, for example) no matter how often the staff corrected her. She knew an applause line that would please audiences, and that was enough for her.

But hold on a moment. Am I simply repeating a slanted partisan view? Decide for yourself if you see the film. Adapted from a best-selling book with the same title by John Heilemann and Mark Halperin, it draws on hundreds of interviews with McCain camp insiders, and although Palin’s supporters are protesting its negative portrait, the facts and dialogue seem to be accurate. When Newsweek’s David Frum asked Schmidt what he thought about the film, he said it was “an out-of-body experience.” Neither he nor Wallace (who confessed that after working with Palin she was unable to vote for McCain) has questioned its accuracy.

Palin was transformed by discovering her ability to mesmerize crowds. She grew intoxicated by her power and rejected guidance from advisers. Nothing like this had ever happened to her before. Exhilarated by the adulation she drew everywhere she went, she was wounded by questions from Couric and others, which she considered hostile “gotcha!” attacks. Tina Fey’s celebrated skits on “Saturday Night Live” hurt her deeply. She found herself loved and ridiculed at the same time.

In her performance, Julianne Moore doesn’t do an impersonation of Palin here, in the sense that Meryl Streep was uncanny in her resemblance to Margaret Thatcher in “The Iron Lady.” She looks about as much like Palin as she can, but that’s not the point. She conveys the essence. In a way, she’s unprotected. Not a hardened, cynical politician, but a woman who has gone through life expecting good things and usually found them. There is a moment in “Game Change” when she’s alone, and we see the hurt and sadness in her eyes when she realizes that people are finding her lacking. She’s like a student who studied hard for the exam and failed anyway. The people love her. Alaska still loves her; that’s why she’s so urgent about the results of an Alaska poll on her popularity. Why are these media creatures being so cruel? Why is everyone picking on her expensive wardrobe? She didn’t want the damn fancy clothes in the first place. Moore conveys these feelings with tenderness and subtlety. Her performance is not a barbed parody, but based on the actress’ instinctive empathy with a character.

As John McCain, Ed Harris has more of a supporting role. He comes across in “Game Change” as a decent man of principle, who has honorable ideas about how a campaign should be conducted and sticks to them. There is a suggestion that he blames himself along with his staff for failing to vet Palin properly; they were too blinded by her appeal to take the time for a cool evaluation.

The film avoids scenes involving the personal lives of the Palins and McCains. Spouses are seen but rarely heard. Palin is depicted as an affectionate mother. This is proper, because the sources for the book and film were expert on the campaign itself, but it wouldn’t be appropriate for them to supply information about private lives.

Woody Harrelson makes Steve Schmidt a pillar at the center of the story, a man driven by frustration as he tries to manage a campaign that Palin is trying to manage herself. As late as election night, they had a shouting match because she wanted to join McCain onstage, where her own concession speech would join his. Schmidt roars at her: “It’s never been done that way in American history! The candidate concedes!” As she walks onstage with McCain, his eyes are still shooting daggers at her as a warning not to grab the microphone for a few words of her own.

Sarah Palin was, Schmidt concluded, the greatest actress in the history of American politics. Abandoning any attempt to brief her before the debates, he hit on the idea of assigning her 25 statements that she would memorize, and then circle around to no matter what the question was. This she did brilliantly. She may have been a bad candidate, but she was a brilliant campaigner, astonishing the staff by her ability to save situations that looked perilous to them.

Seeing “Game Change” is like living again through the campaign of 2008. Much of the dialogue is literally words we’ve already heard. We’re left with the conviction that Sarah Palin would have made a dangerously incompetent president of the United States, and that those closest to her in the campaign, including John McCain, came to realize that.