“…There is nothing either good or

bad, but thinking makes it so. To me it is a prison.”

— “Hamlet” Act 2, scene 2

If you’ve ever suffered from clinical depression, you know the experience is impossible to convey to someone who hasn’t also gone through it. It doesn’t make sense. It’s like trying to describe why you love somebody. How do you explain a lack of feeling, or interest, or pleasure, that is both numbing and excruciatingly painful? How do you account for a disconnection with the past and any conception of a future? It’s not “living in the moment” — it’s being stuck in a moment from which you can’t imagine any escape — not just the feeling that this asphyxiating near-deadness will go on forever, but that you can’t imagine ever having felt any other way (even though, logically, you know that is not possible). You can remember feeling pleasure — no, make that “having felt pleasure” — but you have no memory of what it actually felt like.

One of the (many) reasons I probably connect so strongly with David Fincher’s “Fight Club” (1999) is that, by capturing clinical depression more accurately than any other movie I’ve ever seen (though Laurent Cantet’s “Time Out” and Eric Steel’s “The Bridge” delve mighty deep into that abyss), it helped shake me out of the grips of a depression that was sucking me down at the time. I was the only person in the theater convulsed with laughter from beginning to end, because it was liberating, exhilarating, to see the truth of my own inner experience reflected back at me in its funhouse mirror. I recognized myself in the movie, relished the psychological acuteness of what I was seeing, felt its black absurdity resonate in my poor, chemically imbalanced noggin. From the very first images deep inside the human brain, I felt it could not be about anything else, even though I didn’t know where it was going to go from there.

(Spoilers? Oh, yes.)

Below is my 2 minute, 25 second distillation of what I see as the essence of “Fight Club.” Notice that only one punch is thrown and that the physical/psychological violence is inner-directed (shrinks say depression is rage turned inward) and apocalyptic (small gestures are out of the question when your world is imploding). Press play:

“How’s that working out for you? Being clever.” — Tyler Durden

“Fight Club” is, quite intentionally, a film that is too clever by half, and patently too amused by its own cleverness. That’s also precisely what it is meant to be, as a comedy that takes place entirely inside one immature young man’s head — a thirtysomething white-collar wage-slave Everyman (Edward Norton) who doesn’t have a name but who (for reasons revealed in the movie) we’ll call Jack. At the start of the movie, Jack says he hasn’t slept for six weeks (which is not possible, so we know he’s prone to exaggeration about his own experience). His insomnia has left him feeling that his life is “a copy of a copy of a copy,” as his narration echoes away, fading out of the soundtrack even as he speaks it. A paper Starbucks coffee cup rides back and forth on the copy machine he’s using, and everyone in the office takes a sip of their Starbucks in synch with the office machines.

The first time I saw the movie, up close to a mighty big screen in a sparsely populated theater, and I noticed what appeared to be a chemical splotch on the film, or possibly a bad splice, in this sequence. One or two others went by before I realized that this wasn’t a damaged print (I’ve seen plenty of poorly inspected prints, even on opening days), but a character leaking into the picture. Those flashes of Tyler Durden (later addressed indirectly in the projection booth, where he points out a changeover mark on the print we’re actually watching, and splices frames of pornography into family films) are something I’ve actually experienced when in depression. Senses are dulled, and sometimes — just for a flash — you may think you’ve seen something out of the corner of your eye that isn’t there: a shadow, a bug, a person (see mirror scene in Polanski’s “Repulsion”). You may think you’re going insane. I do.

In the middle of a recent depression (I’m just coming out of one — which is why I haven’t been able to post at my accustomed pace), I had one of the most horrifying experiences of my life. I woke up convinced that I had murdered some people in a particularly bloody fashion. Hacked them apart. I didn’t know who they were, and I didn’t remember how I had done it, but I was awake and suddenly facing the reality of what I had done. But how could that be? I couldn’t have repressed the memory of that, could I? As I started to wake up a little more, I thought: No, you didn’t do it yourself, but you witnessed it.

Either way, it was too much to handle, but you didn’t do anything about it. How could I have not reported what I saw? How could I have forgotten what I saw until just now, when it came flooding back into my consciousness like the blood from the elevator in “The Shining“? (Yes, several recent posts have been fallout from this dream.) It took me about two or three days to convince myself that this had been, in fact, a semi-waking dream. What’s particularly odd to me is that I very rarely have dreams of violence — although I was plagued by dreams of watching a jetliner fall out of the sky in the year before — yes — September 11, 2001. After that, they stopped. No, I don’t believe in precognition, but there it is.

Later, after I was pretty sure I had neither committed nor witnessed mass murder (in real life, and not in the movies) I thought back to “Fight Club” and Jack’s panic and guilt when he realizes he’s been the one who, without being consciously aware of it, has unleashed a fascist/terrorist movement known as Project Mayhem, the fanatical members of which are implementing, under his direction, plans to bring down skyscrapers in Los Angeles. (More 9/11 imagery — though two years before the actual event that so many people described as being so shocking and unbelievable that it was “like watching a movie.” Yeah — this movie.)

Prison by Ikea.

Prison by Ikea.

“Fight Club” begins with Jack feeling trapped in a rut that some people would recognize as true depression. I assume that Northwestern author Chuck Palahniuk, who wrote the novel on which the movie is based, has some first-hand experience with chronic depression — which has nothing to do with feeling bummed about something that’s happened in your life (though that can help trigger an episode). Palahniuk is not subtle, and neither is “Fight Club” — but depression is not subtle, either. It’s all-consuming, and the idea of somebody who could come along and punch you out of it, just so you could feel some kind of real contact with the world instead of seeing it from far away as though anesthetized remove, is a pretty good metaphor. Maybe only somebody who’s experienced depression can fully get in tune with it. I don’t know what it’s like to not have experienced it.

“While both Tyler and Jack are capable of extended neo-macho riffs on the virtues of Fight Club, that doesn’t prevent the whole concept from playing like the delusional rantings of testosterone-addicted thugs. Aside from the protracted beatings, the film is so vacuous and empty it’s more depressing than provocative.”

— Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times (from the “Fight Club” DVD booklet)

“If I had a tumor I’d name it Marla.”

— Jack, “Fight Club“

The depressive state is beyond nihilistic (an adjective freely applied to “Fight Club“), rendering absolutely everything unexplainable, irrational, absurd and utterly meaningless. (It’s recognizable in the suicidal soliloquies of “Hamlet”: “How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable seem to me all the uses of this world!”) But once you emerge from it, its bleakness and absurdity can seem quite funny (in a self-loathing/solipsistic kind of way). Trying to explain it to someone who hasn’t experienced it is fruitless. But, even though it frightens people and makes them want to avoid me like the plague when I get onto the subject (or maybe that’s just their excuse), I can’t help but give it a shot whenever I start obsessing. For now I’ll just say that it feels like being on a desolate planet, where the atmosphere itself is thick and toxic and hard to breathe. You can see the earth indistinctly, but it is unimaginably distant. You can’t remember how long you’ve been on this planet, but you suspect that you may always have been, though intellectually you know that isn’t possible. It just feels that way, and you can’t remember feeling any other way.

So, back to Jack and, eventually, Tyler. Tyler is certainly Jack’s Id, but he’s also Jack’s glib, sophomoric, idea of what he would like to be — hence, the object of his hero-worship. Just before they exchange their first punches, Jack and Tyler have a cliched conversation in a bar about their essential nature as consumers. Jack describes his life in terms of a sofa, a decent stereo and wardrobe that was getting to be respectable: “I was close to being complete.” Then it all blows up in his face. Tyler says (with insufferable adolescent pretentiousness), “The things you own, end up owning you.” Is this a brilliant insight? Hardly. You should be laughing at the characters, not with them. It’s part of what strikes me as so damned funny about “Fight Club“: It is specifically about a (privileged, pouty, petulant, spoiled, incomplete, self-pitying) upper-middle-class white urban heterosexual male in his 30s trying to figure out who he is versus who he thinks he is supposed to be — circa 1999, eve of the supposedly apocalyptic new millenium. You wonder why it’s packed with exaggerated macho posturing? Look around. (The homoeroticism in the film is more accurately narcissism, and I find it fascinating that so many women seem to recognize the pinpoint truth of its portrayal of men than a lot of men do. Then again, who doesn’t want to be as cool as Brad Pitt/Tyler Durden, an effortlessly beautiful man whose terrible, tacky wardrobe and bizarre hygiene both distort and perversely enhance his beauty and coolness? That bit with the rubber glove as he’s having sex with Marla is hilarious — an obscurely tantalizing sexual aid not unlike the buzzing box in “Belle de Jour.”)

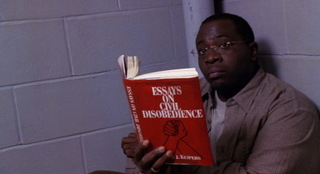

I think of the inspired “Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle” (and the brilliant “Pineapple Express“), two stoner-buddy adventures that are about (and, in fact, are) the movies these guys would make up while smoking a bong on the couch — the movies they would like to see, and star in. (See Jean-Pierre Leaud’s plaintive comment in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Masculine Feminine” about “the film we had dreamed, the film we all carried in our hearts, the film we wanted to make… and secretly wanted to live.”) So when, for example, Harold is thrown in jail, his cellmate is of course a big black guy… who sits quietly in the corner reading “Essays on Civil Disobedience.” Harold asks what he’s in for. “For being black,” he says. The joke is not so much that he’s the antithesis threatening black thug we have been conditioned to expect in dumb teen comedies, and he is instead a mild-mannered, articulate, bespectacled intellectual who was arrested outside a Barnes & Noble and who winds up quoting the Desiderata — a proto-New Age poster/plaque phenomenon of the 1970s akin to Kahil Gibran’s “The Prophet” or “Love Means Never Having To Say You’re Sorry.” What’s funny is the concept that you know the movie knows what a trite and belabored joke that is. The punch line is yet another well-timed reversal, a crass endorsement of racial stereotypes that, of course, isn’t. (My complaint against the cliches of “American Beauty” is that I think they are intended to be taken at face value — like the gruff military guy who turns out to be a closeted gay. But, as Tyler says, I could be wrong. But I don’t see the evidence in the movie.)

As for the violence: Damn right it’s pointless. That’s the point. It’s not about pummeling flesh, but about punching through a big ol’ sack of psychological insulation. Why does Jack impulsively beat the crap out of Jared “Angel Face” Leto’s gilt-framed puss? He says it out loud in the movie: “I felt like destroying something beautiful.” Next question?

I know that what I’ve written here is at least as much about me as about “Fight Club” itself, but that’s why I re-published the earlier entry first. I’m attempting to show how my response to “Fight Club” (which I still defend as a terrific movie) is informed — or, if you prefer, influenced — by my personal experience. I could say the same thing about other favorite movies, like Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall” or Wim Wenders’ “Kings of the Road” or Buster Keaton’s “Our Hospitality.” As I’ve said before, I don’t expect to change anybody’s opinion of “Fight Club,” not only because views in either direction tend to be quite visceral (as they damned well should be), but because my take on it is so personal. I don’t mean to use depression as a way to rationalize my enthusiasm for the film, but maybe I am to some extent. As with the depression itself, I can only try to explain what I experience.

* * * *

Endnote: I’d like to address some of the comments in the “Fight Over Fight Club” post. First of all, feel free to hate the movie. That’s a perfectly healthy reaction to a film that, in its time, It is contemptible — though not necessarily in the ways many of its detractors (i.e., most critics and audiences in 1999) have claimed. (How “violent” can a comedy about a guy beating up on himself with his bare fists really be?) Like David Cronenberg’s “Crash,” the movie was pilloried, even by many within the movie industry, who considered it damaging and dangerous. This is the context in which my 1999 article appeared.

According to Sharon Waxman’s 2005 book “Rebels on the Backlot” (which, I admit, has to be taken with a grain of salt because some chapters are riddled with factual errors and misinterpretations), the heads of distribution and marketing at Fox “disliked the film intensely.”:

Ed Norton recalled that in the very first marketing meeting for the film with Fincher and the studio, [marketing chief Robert] Harper opened the discussion with the following: “Can anyone tell me one f***king thing about this movie that is funny?” […]

[Critic David Thompson] wondered if Fincher wasn’t a terrorist of sorts; “I can’t help wondering whether the social scientist in Mr. Fincher wouldn’t be like the cat that swallowed the cream if a riot of copycat fisticuffs ensued…. David Fincher’s bristling attitude is no defense against rubbish.” […]

[Critic] Stephen Hunter seemed to praise the movie in the Washington Post despite himself…. “Understand, I am not writing a defense. The movie is indefensible, which is what is so cool about it. It’s a screed against all that’s holy and noble in man, a yelp from the black hole.” […]

The issue migrated off the arts and leisure pages onto the opinion and editorial pages. “Fight Club” was repugnant. “Fight Club” was immoral. “Fight Club” was a disgrace. Even people within Hollywood were outraged. […]

[Hollywood Reporter editor Anita Busch] wrote that the film “will become Washington’s poster child for what’s wrong with Hollywood. And Washington, for once, will be right…. The film is exactly the kind of product that lawmakers should target for being socially irresponsible in a nation that has deteriorated to the point of Columbine.” Busch also presided over two news articles that slammed the film, including one that quoted producers and agents (anonymously, of course) saying the movie was “loathsome,” “absolutely indefensible,” and “deplorable on every level.” […]

The vice chairmen of Paramount’s Motion Picture Group, Robert Friedman, pulled aside producer Art Linson at the Paramount commissary and pleaded, “How could you?”

And so on. Of course, I didn’t know all of this when I first saw the movie, and was only aware of a tiny sliver of it when I wrote my 1999 article. But I’m not surprised. I still think a lot of people like it (and loathe it) for the wrong reasons. But they are not my reasons. If I read the movie the way many of its detractors do, I’d hate it, too.

The hyper-glossy/faux-grimy style of the movie precisely captures what it’s about: commercial culture’s ability to co-opt and capitalize upon anything remotely rebellious and individualistic, and turn it into consumer goods. (See how fast the major record labels subsumed the “counter-culture” of the 1960s, or how Hollywood emulated the “indie” spirit of “Easy Rider” or “Pulp Fiction,” or how the music industry immediately embraced and absorbed Seattle’s “grunge” scene and slapped it with the marketable mainstream “alternative” label.)

Why, you may ask, does the movie look like a GQ or Vanity Fair layout (or an Ikea catalog centerfold)? Why does it take what now look like easy potshots at Starbucks or Apple? Because it is indeed emulating the style it’s criticizing, a world in which nuclear families themselves are franchises — as Fight Club becomes. (In the case of the movie itself, the theatrical marketing campaign failed miserably.) Jack and Tyler rant and rave against consumer culture, Microsoft, Starbucks, Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger and the masturbation known as self-improvement — but they exist in that world, and are products of it. As they walk past a naked Gucci boy ad on a bus stop, Jack asks Tyler: “If you could fight any celebrity, who would it be?” For Tyler it’s Hemingway (a celebrity!), and for Jack it’s “Shatner.” Are these guys (er, is this guy) phony and hypocritical about the phoniness and hypocrisy of contemporary capitalist society? Yes. So is Holden Caulfield. That’s part of the joke, and part of the poignancy.

* * * *

P.S. About my dream… I attribute it to some late-night conversations about the amazing documentary “The Staircase” and Errol Morris’s “Standard Operating Procedure,” then staying up very late the two previous nights and watching “Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired” and “Ghosts of Abu Ghraib.” What can I say? I’m an impressionable fellow (and you know what happens to impressionable fellows; they lose their… bearings). There are themes about blood, guilt and repression/denial that run through all these documentaries, but perhaps the most powerful for me was “Ghosts of Abu Ghraib” (the essential companion piece to Morris’s film) in which soldiers stationed there described how they had to consider themselves already dead in order to stay there without going insane. Once they had shut down, out of necessity, the world seemed like a hallucination to them. They were numb, but also put in the position that Noah Cross asserts in “Chinatown“: “Most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place they are capable of anything.” What most terrifies me is the truth of that statement. (And I think it’s one of the lessons of Abu Ghraib. There is no “them,” only us.)

My dream-dilemma was, in some ways, the inverse of Hitchock’s “Wrong Man” obsession. It wasn’t that I was accused and convicted of something I didn’t do, it was that I had done something that nobody, including myself, had previously known about. My sentence, you might say, was to learn how to live with that knowledge (I just saw “In Bruges” last night, my favorite movie so far this year) — and my need to confess it, with the fear that no one would believe me because I didn’t know how to find the evidence. If you’ve seen any of the above movies, you will detect some of the connections.

Especially odd: The very next week I started to watch the first season of “Heroes” on DVD. One of the characters has a split personality (which works nicely as a metaphor for manic depression) and basically lives my dream! It was pretty shocking to watch. She wakes up to find blood and bodies all over her garage studio, wonders who could have committed such atrocities, and then has to face the fact that it was herself (or her alternate self). Another character has nightmares of a nuclear explosion that devastates New York — and in which he himself is the bomb that causes it. Watching these things was rather uncanny under the circumstances.

I somehow feel that my life will always be divided into before that dream (because it extended so far into my waking life) and after it. The way I look at it, I don’t know (and hope I never do) what it’s like to slaughter a bunch of people. But I know exactly what it feels like to have slaughtered them. Because I actually thought I had. And, like it or not, I can’t just say, “Oh, it was only a dream” (only a movie, only a movie). I still have to live with what it felt like.

P.P.S. Please read critic Michael Atkinson’s essay, “Ghost in the Shell,” about his brief bout with depression. His experience doesn’t quite mirror my own (maybe it’s somewhat different for everybody), but it’s one of the most insightful pieces I’ve ever seen on the subject.