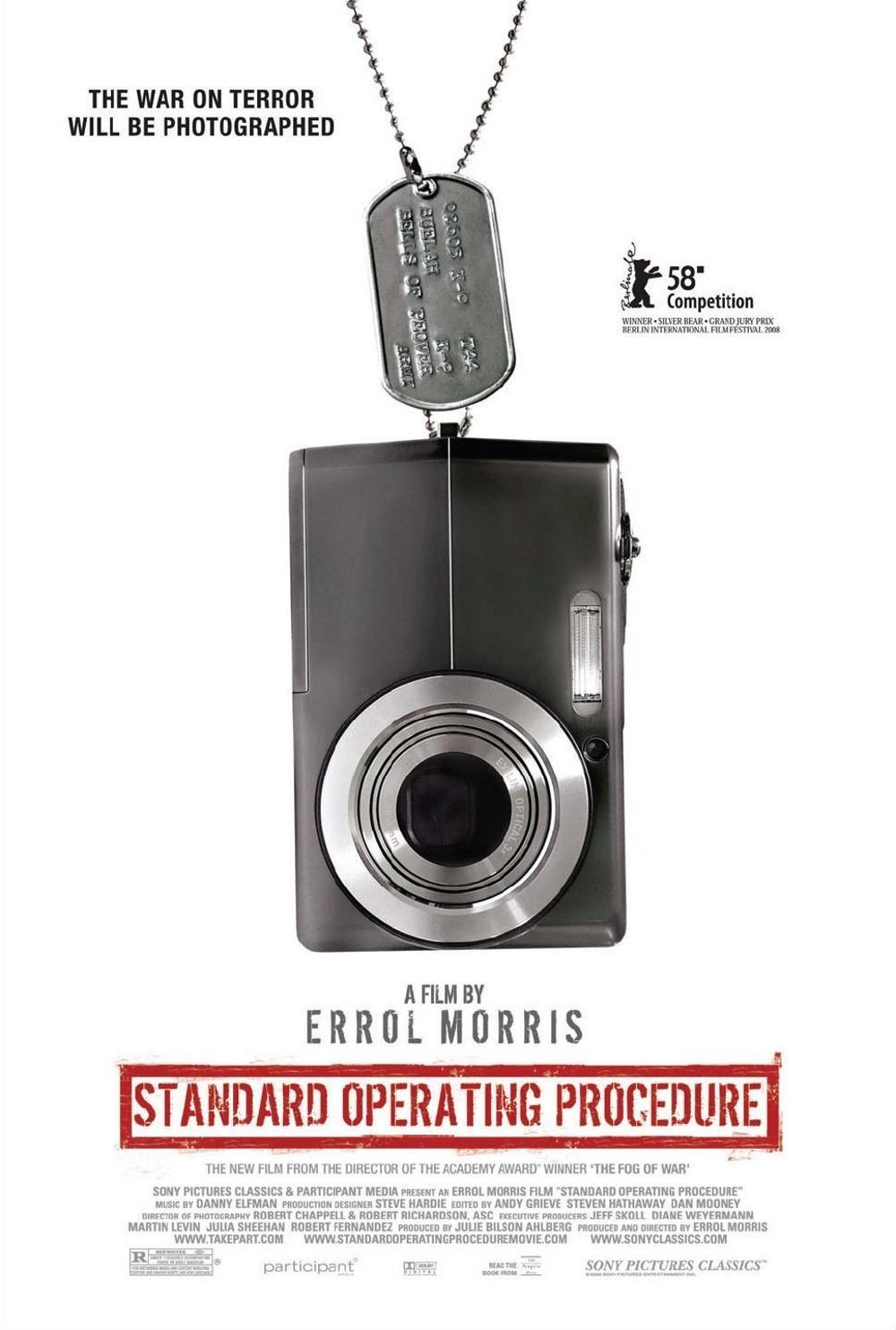

Errol Morris’ “Standard Operating Procedure,” based on the infamous prison torture photographs from Abu Ghraib, is completely unlike anything I was expecting from such a film — more disturbing, analytical and morose. This is not a “political” film nor yet another screed about the Bush administration or the war in Iraq. It is driven simply, powerfully, by the desire to understand those photographs.

There are thousands of them, mostly taken not from the point of view of photojournalism, but in the spirit of home snapshots. They show young Americans, notably Lynndie England, posing with prisoners of war who are handcuffed in grotesque positions, usually naked, heads often covered with their underpants, sometimes in sexual positions. Miss England, who was about 20 at the time and weighed scarcely 100 pounds, often has a cigarette hanging from her mouth in a show of tough-guy bravado. But the effect is not to draw attention to her as the person who ordered these tableaux, but as a part of them. Some other force, not seen, is sensed as shaping them.

This invisible presence, we discover, is named Charles Graner, a staff sergeant Lynndie was in love with, who is more than 15 years her senior. She does what he suggests. She doesn’t question. But then few questions are asked by most of the Americans in the photographs, who are not so much performing the acts as being photographed performing them.

“Pictures only show you a fraction of a second,” says a Marine named Javel Davis, who was a prison guard but is not seen in any of them. “You don’t see forward and you don’t see backward. You don’t see outside the frame.” He is expressing the central questions of the film: Why do these photos exist, why were they taken and what reality do they reflect? What do we think about these people?

Those are the questions at the heart of many of Morris’ films, all the way back to his first, “Gates of Heaven” (1978), in which to this day I am unable to say what he feels about his subjects or what they think of themselves. The answers would be less interesting anyway than the eternally enigmatic questions. Morris’ favorite point of view is the stare. He chooses his subjects, regards them almost impassively, allows their usually strange stories to tell themselves.

There is not a voice raised in “S.O.P.” The tone is set by a sad, elegiac, sometimes relentless score by Danny Elfman. The subject, in addition to the photographs, is Morris’ interview subjects, seen in a mosaic of closeups as they speak about what it was like to be at Abu Ghraib. Most of them speak either in sorrow or resentment, muted, incredulous. How had they found themselves in that situation?

Yes, unspeakable acts of cruelty were committed in the prison. But not personally, if we can believe them, by the interviewees. The torturers seem to have been military intelligence specialists in interrogation. They, too, are following orders, and choose to disregard the theory that the information is useless since if you torture a man enough he will tell you anything.

I cannot imagine what it would be like to be suspended by having my hands shackled behind my back so tightly I might lose them. Or feeling I am being drowned. And so on — this need not be a litany of horrors.

More to the point of this film is that the prison wardens received their prisoners after the tortures were mostly committed, and then posed with them in ghastly “human pyramids,” “dog piles” or in scenes with sexual innuendo. Again, why? “For the picture.” The taking of the photos seems to have been the motivation for the instants they reveal. And, as a speaker observes in the film, if there had been no photos, the moments they depict would not have existed, and the scandal of Abu Ghraib would not have taken place.

Yes, some of those we see in “Standard Operating Procedure” were paid for their testimony. Morris acknowledges that. He did not tell them what to say. I personally believed what they were telling me. What it came down to was, they found themselves under orders that they did not understand, involved in situations to provide a lifetime of nightmares.

They were following orders, yes. But whose? Any orders to torture would have had to come from those with a rank of staff sergeant or above. But all of those who were tried, found guilty and convicted after Abu Ghraib were below that rank. At the highest level, results were demanded — find information on the whereabouts of Saddam Hussein (whose eventual capture did not result from any information pried loose by torture). At lower levels, the orders were translated into using torture. But there was a deliberate cutoff between the high level demanding the results and the intermediate level authorizing the violation of U.S. and international law by the use of torture.

At the opening of the film, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld is seen, his blue blazer hooked over one shoulder, his white dress shirt immaculate, “touring” Abu Ghraib. He is shown one cell, then cancels his tour. He doesn’t want to see any more.

And so little Lynndie England is left with her fellow soldiers as the face of the scandal. And behind the photos of her and others lurk the enigmatic figure of Sgt. Charles Graner, who was not allowed by the military to be interviewed for this film. I imagine him as the kind of guy we all knew in high school, snickering in the corner, sharing thoughts we did not want to know with friends we did not want to make. If he posed many of the photos (and gave away countless copies of them), was it because he enjoyed being at one remove from their subjects? The captors were seen dominating their captives, and he was in the role, with his camera, of dominating both.

Remember the photo of Lynndie posing with the prisoner on a leash? His name, we learn, was Gus. Lynndie says she wasn’t dragging him: “You can see the leash was slack.” She adds: “He would never had me standing next to Gus if the camera wasn’t there.”