It’s an awesome sight from up there, the wind and dizzying height halting your breath as you gaze across the strait. The sun makes silver ripples on the churning blue-green water and the horizon glows blindingly bright at the time of day when the sky and the sea converge. The cliffs, crinkled with shadows, form a paradisiacal gateway. And then, in the periphery, there’s a tiny momentary rupture in the mythical postcard landscape. A small white splash flickers in the water. And in the great bright cacophony of the scene, Icarus disappears beneath the surface.

That’s a description of Peter Breughel’s painting, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” and William Carlos Williams’ poem by the same name, intermingling with images from Eric Steel’s “The Bridge,” a film about 24 deaths and one survivor in a year in the life of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. “The Bridge” consciously invokes Brueghel, and after I’d watched the movie and looked up the painting again, hundreds of images of the Golden Gate from “The Bridge” (and my memory) came rushing back to me, as though projected at high speed over Breughel’s canvas. Each small white splash, of course, marks the end of a life.

In the United States, about 30,000 people kill themselves every year, almost twice as many as kill one another. The Golden Gate Bridge, where 20-plus people jump to their deaths every year, holds a special place in our national (and cinematic) imagination — and not just as a spectacular feat of engineering. Most die on impact; others are dragged under by the chilly currents. According to a title at the end of “The Bridge”: “More people have chosen to end their lives at the Golden Gate Bridge than anywhere else in the world.”

Eleven men died building what was the world’s largest suspension bridge when it was completed in 1937. Since then, it’s estimated that more than 1,300 have leaped to their deaths from the span, and only 26 jumpers (including a young man interviewed in the film) have survived the 4-second, 220-foot, 75 mph plunge.

Any movie fan watching “The Bridge” will remember Kim Novak’s swooning plunge into the bay (from under the bridge, but with the Golden Gate soaring above) in Alfred Hitchcock’s tragic romance, “Vertigo.” And the grandeur of the bridge, as the iconographic setting for a final dramatic gesture, has an allure for some that’s as strong as the currents in the waters below. The bridge “has a false romantic promise to it,” observes the friend of a man who jumped. “But so what if his story has that at the end? He’s gone.”

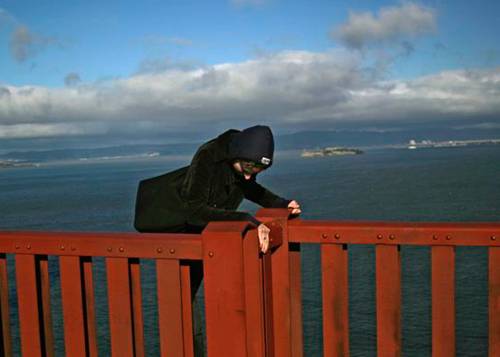

In 2004, Steel and his crew set up cameras to photograph the bridge from dusk to dawn over an entire year. In addition to capturing magnificent shots of the bridge in all its formidable glory, they also trained telephoto cameras on the mid-span to catch jumpers and potential jumpers in the act. They paid special attention to people who were alone, hesitant, lingering or pacing a little too long, sometimes crying or just staring. Each time the filmmakers noticed someone who seemed to be preparing to leap, they alerted the Bridge Patrol. Steel estimates they prevented six jumps that year.

“The Bridge” is neither a well-intentioned humanitarian project, nor a voyeuristic snuff film. It succeeds because it is honest about exhibiting undeniable elements of both. It’s a profoundly affecting work of art that peers into an abyss that most of us are terrified to face — not just the waters of the bay, but the human mind — and reflects on the unanswerable question: What makes someone take that leap into the void?

The mother of a boy who was fascinated — nearly obsessed — with the bridge, and who jumped from it to his death at 21, fears (like many family and friends) that she could have been the cause of some of the damage that made her son want to die, or that she could have done more to prevent his death. But finally someone tells her, point blank: “It’s not about you. It has nothing to do with you.” In the end, nearly everyone interviewed seems to have felt that their departed had gone away long before the jump, as if they were already out on the deck, alone and unreachable.

The deeper the movie looks into the lives of its suicides, the more patterns emerge, not unlike the common but unpredictable behaviors exhibited along the railings. Most of the jumpers have histories of mental illness, and spent days, months or even years contemplating, discussing, threatening, planning and preparing for their final decisive act. One woman likens the process to “finding a college to attend,” and says that, despite its destructive nature, “there’s a lot of rational thought that goes into an act that a lot of people just consider irrational.”

Witnessing the last few moments of these people’s existence, I thought of Michael Apted’s “Up” documentaries, which have followed the contours of a handful of lives for 49 years now, revisiting them at seven-year intervals. “The Bridge” views human life from the other end of the spectrum — showing the end, and then working back from there.

And because these jumpers chose such an open and public way to end their lives, I have no ethical problem with what the cameras observe; amateur photographers often catch the same sights inadvertently. One survivor tells of being interrupted by a German tourist who asked him to take her picture, just as he was preparing to jump.

Looking this closely and intently into suicide, you almost fear too much empathy, the way you dread the vertigo that accompanies acrophobia: What you’re afraid of is not so much that you might fall, but that impulse within you that wants to eliminate the yawning tension between you and the surface below. But as several in the film acknowledge, the eternal dilemma of suicide is not something we can diminish by hushing it up or mischaracterizing what it is.

“The Bridge” is brave and unflinching, unshakably haunting and deeply mysterious. I doubt I’ll forget it until the day I die.