Above: That gritty Hollywood literalism and/or naturalism: “Off-putting to the contemporary sensibility.”

I was wrong. Last night, just before going to bed, I read Stephen Metcalf’s “Dilettante” column, “The Worst Best Movie: Why on earth did ‘The Searchers’ get canonized?”. This did not make it easy for me to get to sleep, so I dashed off a preliminary response in which I harshly characterized Metcalf’s piece as an “inexcusably stupid essay… about a classic John Ford Western.” But now, re-reading the column in the light of day, I realize that Metcalf was hardly writing about “The Searchers” at all. And nearly every observation he does make about the film itself is cribbed from something Pauline Kael wrote (see more below). He’ll just fling out an irresponsible, non sequitur comment like, “Even its adherents regard ‘The Searchers’ as something of an excruciating necessity,” and let it lie there, flat on the screen, unexplained and unsupported. So, while I stand by my claim that what Metcalf has written is stupid and inexcusable (for the reasons I will delineate below), I don’t think it has much to do with “The Searchers.”

Instead, Metcalf is reacting to his own perception of the film’s reputation (and in part to A.O. Scott’s recent New York Times piece admiring “The Searchers”), using the movie to snidely deride people Mecalf labels “film geeks,” “nerd cultists” and:

… critics whose careers emerged out of the rise of “film studies” as a discrete and self-respecting academic discipline, and the first generation of filmmakers — Scorsese and Schrader, but also Francis Ford Coppola, John Milius, and George Lucas — whose careers began in film school.

(The latter are later characterized as “well-credentialed nerds.”) The fault, then, in Metcalf’s mind, is not so much in the film as in those who brazenly take film seriously as an art form. Using “The Searchers” as an anecdotal, ideological bludgeon, Metcalf attempts to attack the impudent and insidious notion that movies are worthy of serious study and artistic interpretation. Holy flashback to Clive James!

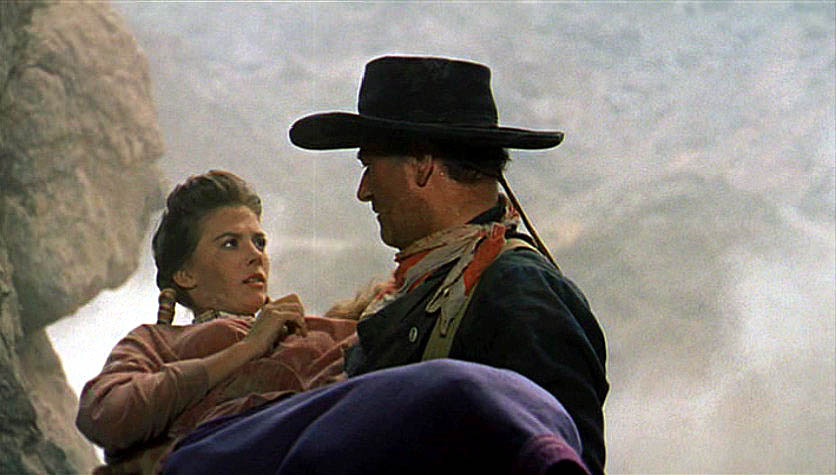

“What makes a man leave bed and board and turn his back on home?” The physical grace of John Wayne.

I wonder what Metcalf means by the phrase “discrete and self-respecting academic discipline”? Is he saying that film, if studied in academia at all, should merely be used — as it so often has been — solely as an audio-visual aid in literature or drama or history courses, and not taught as film? As such, should film be put in its rightful place as an “inferior” medium, groveling before superior books and plays with a reverential, self-abasing cry of “We are not worthy! We are not worthy!”? That’s certainly been the case in many American schools and universities over the past half-century or so….

Metcalf confesses that he has, in fact, seen “The Searchers” — recently, once, and for the first time:

Coming to “The Searchers” for the first time, I was surprised at how fidgeted-together this supposedly great film is, how weird its quilting is, of unregenerate violence with doltish comic set pieces, all pitched against Ford’s signature backdrop, the buttes and spires of Monument Valley. Though visually magnificent, the movie is otherwise off-putting to the contemporary sensibility, what with its when men were men, and women were hysterics mythos and an acting style that often appears frozen in tintype. (Hank Worden’s turn, as the lovable village idiot, is particularly gruesome in this respect.)

First of all, watch out for anyone who uses a lame term like “visually magnificent” to describe a movie without offering further elaboration and evidence. Film is a visual medium; if all a movie does is to offer up pretty pictures (see “Thelma and Louise” for an egregious and inappropriate use of excessive pictorialism), then that hardly qualifies as “visual magnificence,” any more than the prettified mallworks of Thomas Kinkade (“The Painter of Light”) constitute “magnificent” landscape painting.

But the key phrase here, I think, is “off-putting to the contemporary sensibility.” Horreurs! Metcalf insists that “this silly film” be judged through the lens of political correctness, circa 2006. Never mind that it was made in 1956, an opening title sets it in “Texas 1868” (in an isolated homestead in the middle of the Southwestern American desert, no less), and that it is overtly stylized in every respect. “The Searchers” — from its opening shot of the doorway — is self-consciously mythological, poetic, and, in its characters’ choreographed body language, even balletic. (To give Metcalf some credit, he does acknowledge that the moment when Ethan lifts Debbie, and then cradles her in his arms is “one of the more thrilling moments in anyone’s movie-watching life.” I just wish he would speak for himself and refrain from exerting authority over others’ responses. And how can a movie that builds to such a thrilling moment also be “impossible to enjoy”? Does that moment exist in isolation from the rest of the movie?)

The archaic-sounding spoken language (precursor to the profane blank verse of “Deadwood”) isn’t “realistic,” either, and isn’t inteded to be — and that may be off-putting to contemporary sensibilities, like the language of “The Odyssey,” “Beowulf,” “Hamlet,” “Moby Dick” and “Miller's Crossing,” to name a few. When Ethan shoots out the eyes of a dead Comanche, the Reverend (Ward Bond) asked what good that did him. Ethan replies: “By what you preach, none. By what that Comanche believes, ain’t got no eyes he can’t enter the spirit land, has to wander forever between the winds. You get it, Reverend.” Then, turning to Jeffrey Hunter: “C’mon, Blankethead.” What a marvelous mix of rhythms, tones and images are contained in that one brief speech. But that’s exactly what may make some modern folks “uncomfortable.” As critic Michael Atkinson described it, “The Searchers” is “is as far from an ordinary mid-century western as ‘King Lear’ is from a soap opera.”

“Baby!” Martha pushes her youngest child Debbie out of the window into the wilderness, while her body also yearns to hang onto her as long as she can. She will never see her daughter again. I find this moment heartbreaking because the eloquent movements of the actors express something beyond the reach (and maybe the ken) of naturalism.

Like his model Pauline Kael (“The lines are often awkward and the line readings worse… the performances are highly variable”), Metcalf writes that “The Searchers” is “alternately sodden and convulsive in its acting.” (That sure sounds highly variable to me!) But, as if it weren’t obvious from the movie itself, Ford began in the days of silent cinema (he directed 67 films between 1915 and 1928), and the performances in this film are quite openly characteristic of silent film styles. Call them melodramatic or expressionistic; as I said, I prefer “balletic” or “poetic.” Watch the way the mother reaches out in anguish and desperation after her youngest daughter as she is passed out the window to escape a deadly raid. Or the way Ethan stands in the doorway at the end. Or (as we shall discuss in a moment), that indelible moment in which Ethan grasps Debbie and lifts her into the air. Are these stylized, exaggerated movements sullen or convulsive? Some may think so; I think they’re essential to the style, the atmosphere — and the spell — of the movie, and help account for why it remains so beloved and fascinating today. (As I mentioned before, “The Searchers” even ranked on the AFI’s decidedly non-academic list of 100 Greatest American movies, in between those two silly, sodden and convulsive museum pieces “Pulp Fiction” and “Bringing Up Baby,” the latter a shameless screwball comedy featuring some outlandish performances — one must say, in range and tone, they are “highly variable” — from a pair of ancient relics called Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn.)

Metcalf also makes the mistake (it’s almost a pathetic fallacy) of asserting that if something can’t — or won’t — be articulated by the filmmakers themselves, then it isn’t suitable for discussion by anyone else. In Metcalf’s formulation, only the artist can define his own art. He writes:

That Ford should be admired and dissected by a legion of academics would have been amusing to Ford, a self-styled man’s man (and by many accounts, a self-styled drunk’s drunk) who once said, “My name is John Ford. I make Westerns,” as laconic a kiss-off to one’s nerd-cultists as one could imagine.

Martha opens the door, and the movie, to greet the returning Ethan.

Through a doorway, into another emotional dimension: Martha gently caresses Ethan’s coat.

The Reverend pretends not to notice the parting scene between Ethan and Martha.

Ethan discovers Martha’s body, out of view, inside a burned-out structure. This time, the camera looks out at Ethan the Outsider from beyond the threshold of death, rather than within the shelter of civilization as in the opening and closing shots.

(Actually, Ford introduced himself that way, famously, during a notorious Director’s Guild meeting, speaking out against Cecil B. DeMille and the anti-Commie Red-baiters in the membership, but more about that below. Perhaps Metcalf is thinking of William Shatner and his “kiss-off” to Trekkies in an old “SNL” sketch.) Howard Hawks had a similar attitude about his work. To filmmakers like Ford and Hawks, directing movies was their job, and they were professionals. And Shakespeare considered himself a popular entertainer. But so what? Since when do someone’s overtly stated artistic ambitions serve to limit or enhance the aesthetic value of the art itself? Ever heard the adage, “Trust the art, not the artist”? If El Greco said his “View of Toledo” was meant to be just a picture postcard, would that lessen its reputation as a great painting? If Stravinsky dismissed his “Rite of Spring” as mere ballet programme music, would that diminish what we hear in it? And, conversely, if Neil Simon proclaims himself the greatest playwright of the 20th Century, does that make it so? I sure hope not. I suggest Metcalf watch Peter Bogdonovich’s “Directed by John Ford” to see just how irascible Ford could be with critics and academics; it doesn’t change his work one bit. (Later Metcalf quotes a crude and laconic explanation, given by John Wayne in some unidentified interview, for why Ethan does what he does — as if the Duke could offer the final word in artistic interpretation.)

Metcalf falls into another muddle when he cutely attempts to reduce “Hamlet,” “The Turn of the Screw” (or, maybe “The Innocents”?) and “The Searchers” to a series of seminar questions. I will quote him and — in the spirit of his questions — provide the simplistic answers he seeks in italics:

Now, “Why didn’t he kill her?” is right up there with “Why does Hamlet dither?” and “Did the governess really see Quint and Miss Jessel?” as one of the great seminar unanswerables; it is sure to keep discussion going for the allotted 50 minutes, along with: Wait, why did he want to kill her in the first place? (Could it be because, in his xenophobic view, she had been kidnapped into a fate worse than death? Try asking this question of the Muslims who, under Sharia law, kill their own wives and daughters when they are raped or commit adultery. What might it mean, to Ethan and to the movie, if a nubile white girl — his brother’s daughter — is kidnapped, raised and bred within a tribe of people he sees as heathens and savages? Know anything about the Judeo-Christian obsession with bloodlines, as detailed in the bible?)

Was he in love with Debbie’s mother, his milquetoast of a dead brother’s dead wife? (Did you perhaps intuit something like what the Reverend notices — and discreetly chooses to respect and/or ignore — about the gestures and glances that pass between Ethan and Martha? What do you think?)

Why is Debbie the only hint of good sex in the movie? (OK, I’ll bite: You say Debbie, as played by the “ravishing” Natalie Wood, is the heart of the movie’s “kinky allure.” How do you think Ethan feels about that, imagining what those “young bucks” might be doing with his neice? If, as you say, the movie’s other women [even Lucy?] are seen — by Ethan or by the film — as “sexless,” including the forbidden Martha, where does that concentrate all the movie’s repressed sexual energy?)

Are Ethan and Scar doppelgängers? (Does the pope defecate in the woods? Are bears a national threat?)

Does Ethan spare Debbie because the scalping of Scar has purged him of his own most perturbing desires? (You think he’s purged? If so, why doesn’t he come into the house at the end of the movie? Why does he turn and walk away?) Who knows?

Ah, yes, “Who knows?” Because art should answer questions, not raise them, right? Because any question that can’t be addressed, definitively, after a single viewing of a film is not worth asking? Metcalf’s reductive view of art (and, especially, movies) is, well, off-putting to any critical or aesthetic sensibility.

The answer to why Ethan decides not to kill Debbie isn’t expressed in rational, linear thought or language — it’s expressed in the thrilling moment Metcalf cites, a moment that is beyond reason or words. It’s expressed in the motion and timing of Ethan’s lifting and cradling Debbie when he finally, after all these years, gets his hands on her. If there’s a human being who honestly doesn’t understand the answer to the question “Why didn’t he kill her?” in that moment, who doesn’t feel it’s right and necessary to the movie, who thinks it is nothing but an artificial, tacked on Hollywood “happy ending,” then I don’t quite know what to say. To oversimplify: When Ethan lifts her, she is real for the first time in years, not just the abstract object of his obsessive quest. She’s his flesh and blood, the daughter of his dead brother and the woman he loved. He’s already seen what happened to his elder niece Lucy; but now he holds one possible future in his hands. I feel all of this in that moment — and it has nothing to do with “problematizing” the movie in terms of race, gender, politics, or the public personae of Wayne and Ford.

Not that it has anything to do with “The Searchers,” but Ford was a staunch Roosevelt Democrat, what Republicans today would call a radical Hollywood liberal. Metcalf falsely conflates the personal politics of Wayne and Ford, which in fact was a source of friction between them. (See the recently broadcast American Masters documentary, “John Ford/John Wayne: The Filmmaker and the Legend” — which happens to be included with the new 2-disc DVD set of “Stagecoach.”) Ford famously attacked Cecil B. DeMille and the Commie witch-hunting alliance backed by John Wayne at a Directors Guild meeting DeMille tried to oust Joseph Mankiewicz from the Guild presidency and smear him as a Communist sympathizer.

To quote (flaming lefty!) critic Joseph McBride, who wrote a book-length study and interview with Ford along with Michael Wilmington:

Particularly among younger and more liberal audiences, the kind we knew [in the late ’60s and early ’70s] in Madison (where students in our film class had hooted at “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”), Ford was seen as nothing more than a flag-waving reactionary who supported the Vietnam War and hung out with John Wayne. That was part of Ford’s personality at the time — a longtime progressive, he had turned to the right because of the war and his general unhappiness with the way America had not lived up to his vision of its potential — but there was so much more to the man and his work that many people simply could not see.

I’m impressed, and moved, by this assessment of Ford’s once-progressive vision of America (on-screen and off-), a vision he lost even as his view of Native Americans mellowed and ripened into “Cheyenne Autumn.” Today, anyone claiming that America has not lived up to its potential is most likely to be accused of being a radical left-winger; the right defends the status quo as evidence of America’s innate greatness, and proof that we do not have to change or become “better” because we already are. (Indeed, the only way we could get better, according to the reactionaries, is by retreating into an idealized, romanticized past that never existed… outside, perhaps, of mid-century John Ford films like “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon” or “Wagon Master” or “Young Mr. Lincoln.”) But, again, all this has more to do with Metcalf than with “The Searchers.” So, back to the movie:

Ethan lifts Debbie, no longer a little girl, into the air.

“Let’s go home, Debbie.” But can he — or either of them — ever really go “home” again. Guess that’s the subject for another bogus Metcalf seminar.

Perhaps Metcalf’s worst blunder comes at the end, when he fatuously/facetiously writes:

Ah ha! So that is why Ethan doesn’t kill Debbie! Because at the end of the day, the half-crazed auteur must finally give way to the crowd-pleaser, right? And so when Wayne finally hunts down Debbie, only to raise her up, it’s a moment of pure cinema. … Well, I don’t know. And neither did John Ford.

Wow, the arrogance here is… not exactly breathtaking, more like oppressive, asphyxiating. Metcalf has no idea of what John Ford did or did not know — only that John Ford directed this picture, for reasons of his own. Neither does he “know” what I — or you — are capable of enjoying, even though he deems enjoyment of “The Searchers” “impossible.”

If Metcalf wanted to say that he found the movie confounding and not entertaining, then that would have been fine with me. His antipathy and disaffinity for art, criticism, and all things cinematic are evident from what he says about “The Searchers” in particular, and that’s fine. His words speak for themselves. But don’t use “The Searchers” to take gratuitous and ill-supported whacks at film and film studies. And don’t presume to speak for others when you can only speak for yourself.

P.S. Metcalf also blatantly appropriates the language and opinions of Pauline Kael, and misrepresents those of Roger Ebert:

Not coincidentally, pop critics like Pauline Kael, who found much in the film “awkward,” “static,” and “corny,” and Roger Ebert, who finds the movie flawed and “nervous,” have been the most vocal dissenters in the cult of “The Searchers.”

As soon as Roger is out of the hospital, I will ask him if he considers himself a “vocal dissenter in the cult of ‘The Searchers'” — a movie he included in his first volume of “The Great Movies,” and about which he wrote:

The poignancy with which he stands alone at the door, one hand on the opposite elbow, forgotten for a moment after delivering Debbie home. These shots are among the treasures of the cinema.

In ”The Searchers” I think Ford was trying, imperfectly, even nervously, to depict racism that justified genocide; the comic relief may be an unconscious attempt to soften the message. Many members of the original audience probably missed his purpose; Ethan’s racism was invisible to them, because they bought into his view of Indians. Eight years later, in ”Cheyenne Autumn,” his last film, Ford was more clear. But in the flawed vision of ”The Searchers” we can see Ford, Wayne and the Western itself, awkwardly learning that a man who hates Indians can no longer be an uncomplicated hero.

Metcalf gives his “last word” to Kael, who wrote: “You can read a lot into ‘The Searchers,’ but it isn’t very enjoyable.” But he also appears to have given her the first and second and third word. If you read the Kael’s capsule review in “5001 Nights at the Movies,” you’ll find most of Metcalf’s talking points, and even some of the language he passes off as his own. Here’s an excerpt from Kael to be compared with Metcalf’s piece:

It’s a peculiarly formal and stilted movie, with Ethan framed in a doorway at the opening and the close. You can read a lot into it, but it isn’t very enjoyable. The lines are often awkward and the line readings worse, and the film is often static, despite economic, quick editing. What made this John Ford Western fascinating to the young directors who hailed it in the 70s as a great work and as a key influence on them is the compulsiveness of Ethan’s search for his niece (whose mother he loved) and his bitter, vengeful racism. He’s surly and foul-tempered toward Martin, who accompanies him during the five years of looking for the girl (who by then has turned into Natalie Wood, in glossy makeup, as if she were going to a 50s prom), and he hates Indians so much that he intends to kill her when he finds her, because she will have become the “squaw” to what he calls a “buck.” The film doesn’t develop Ethan’s macho savagery; it’s just there–he kills buffalo, so the Comanches won’t have meat, and he shoots out the eyes of a dead Comanche. The sexual undertones of Ethan’s character almost seem to belong to a different movie; they don’t go with the many crude and corny touches in this one. Ford’s attempts at comic relief are a fizzle — especially the male knockabout humor, an episode involving a fat Indian woman called Look (Beulah Archuletta), and the scenes with Hank Worden overacting the role of a crazy man.

(Metcalf writes: “Hank Worden’s turn, as the lovable village idiot [Mose Harper], is particularly gruesome…” I wonder what he thought of the use David Lynch made of the late Worden in “Twin Peaks,” where he played the decrepit room service waiter at the Great Northern. How “gruesome” was that?)

Kael is one of those critics who frequently saw more than she thought she was seeing, or found herself missing the forest for the trees. And in this case, I’d argue that’s exactly what happened. She didn’t have the faintest idea of what was going on in “Rio Bravo” or “El Dorado,” either, and she never understood traditional Westerns (although she was fond of revisionist westerns like those favored by Metcalf, such as “Little Big Man” and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller“). Nor did she ever quite grasp the screen presence of John Wayne (apart from the actor’s off-screen political views in the ’60s and ’70s) the way Godard came to. I think she was narrow-sighted and utterly uncomprehending of “The Searchers,” and many other movies (her review of “2001: A Space Odyssey” is another memorable whopper), but you don’t read Kael for her opinions (which are, in fact, oftentimes not only unsupported but contradicted by her own observations); you read her for the passion and dexterity of her writing. (I could pick apart a Kael review the way Metcalf does “The Searchers” — but I love Kael’s work, for all its flakiness, inconsistencies and bizarre disproportionate verdicts.)

I’m going to give my last word (almost) to Derek, who wrote in a comment to my initial response to Metcalf’s piece (and Kael’s — I think she deserves at least co-author credit): “Yeah, and the language of Moby Dick is a little stilted and purple as well. Why would anyone want to read a blook with such FLAWS!?!”

(OK, one final note: In Dennis Cozzalio’s latest quiz, “Professor Julius Kelp’s Endless Summer Chemistry Test” — about which, more later — one of the questions reads, in part: “What film might be a potential relationship deal-breaker for you?” Quentin Tarantino has systematically used “Rio Bravo” to “screen” potential girlfriends. I’ve never been quite that methodical about it, but I’m not sure I would find much I could respond to within a person who didn’t respond deeply to “The Searchers.” (Or “Nashville,” for that matter. My friend Julia once dumped a guy when she found out he was dismissive of “Nashville.” It’s an indication of a more serious incompatibility of characters…)