“A Perfect World” contains a prison break, the taking of a hostage, a chase across Texas, two murders, various robberies, and a final confrontation between a fugitive and a lawman. It is not really about any of those things, however. It’s deeper and more interesting than that. It’s about the true nature of violence and about how the child is father to the man.

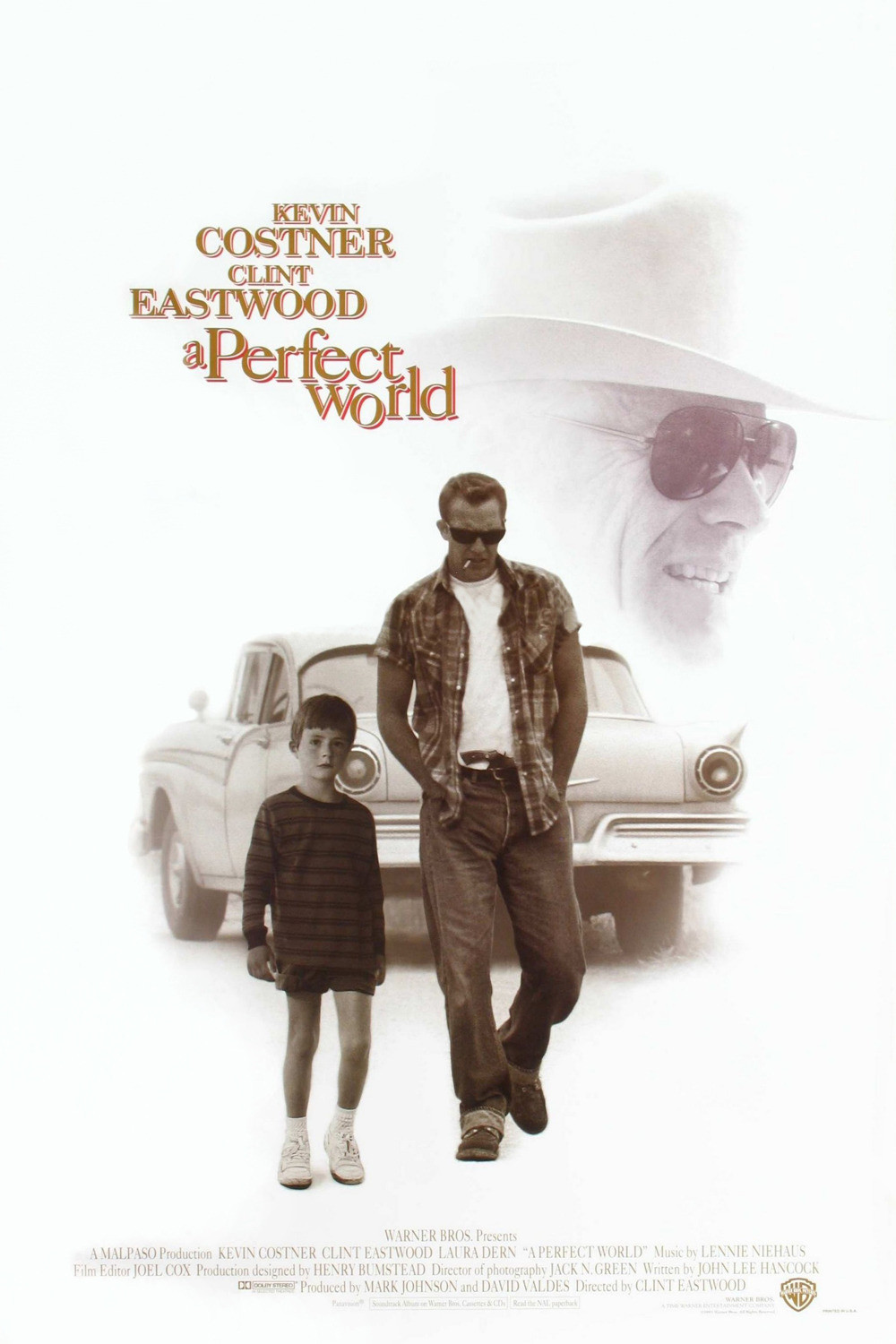

The film brings together the leading icons of two generations of strong, silent American leading men: Kevin Costner, as a fugitive who takes a boy as a hostage, and Clint Eastwood, as the Texas Ranger who leads the pursuit. But the Costner character doesn’t seem really focused on his escape, and the Eastwood character seems somewhat removed from the chase. These two men first met long ago, and they both know this isn’t about a chase. It’s about old, deep wounds.

This is a movie that surprises you. The setup is such familiar material that you think the story is going to be flat and fast. But the screenplay by John Lee Hancock goes deep. And the direction by Clint Eastwood finds strange, quiet moments of perfect truth in the story.

Both Costner and Eastwood are fresh from triumphs at the Academy Awards, but in neither “Dances with Wolves” nor “Unforgiven” will you find the subtlety and the sadness they discover here. Eastwood has directed 17 films, but his direction is sometimes taken less seriously because he’s a movie star. “A Perfect World” is a film any director alive might be proud to sign.

Costner’s character, Butch Haynes, is a young man who drifted into trouble and was sentenced unfairly, to get him out of the way. The Eastwood character, Red Garnett, had something to do with that and has never felt quite right about it. Escaping from prison, Haynes and another convict break in on a mother and her children at dawn. Soon they’re on the road with a hostage, Phillip (T.J. Lowther), 9 or 10 years old.

Before long the other con is gone from the scene and the man and the boy are cutting across the back roads of Texas. In pursuit is Red Garnett, riding in a newfangled Airglide trailer that’s a “mobile command headquarters.” Garnett is saddled with a talky criminologist (Laura Dern) and various other types, including a sinister federal agent who is an expert marksman. The general view is that Haynes is a desperate kidnapper. Both Eastwood and Dern think, for different reasons, it isn’t that simple.

And it’s not. The heart of the movie is the relationship that develops between the outlaw and the kid. You can look very hard, but you won’t be able to guess where this relationship is going. It doesn’t fall into any of the conventional movie patterns. Butch isn’t a terrifically nice guy, and Phillip isn’t a cute movie kid who makes and then loses a friend.

It’s not that simple. Butch, we learn, was treated badly as a boy. His father was absent, his mother was a prostitute, the men in her life didn’t like him much. Butch talks vaguely about going to Alaska. But as the man and boy drive through the dusty 1963 Texas landscape, it’s more like they’re going in circles, while the man looks hard at the boy and tries to see what it means to be a boy, what is the right way and the wrong way to talk to one. He’s trying to see himself in the kid.

There are some murders in the film, all of them off-camera.

One body is found in an auto trunk, the other in a cornfield. We don’t see either killing; Eastwood stays away from the cliche of a gun firing, a body falling, and it’s not until late in the film that someone is shot onscreen, and then in very particular circumstances.

But there is violence in the movie. In the film’s key sequence, Butch and Phillip are given shelter for the night by a friendly black farmer (George Haynes). The next morning, Butch watches as the farmer treats his son roughly, slapping him when he doesn’t behave. It’s the wrong way to treat a kid, but Butch’s reaction is so angry that we realize a nerve has been touched. And as a complex series of events unfolds, we discover the real subject of the movie: Treat kids right, and you won’t have to put them in jail later on. The crucial violence, from which later violence springs, is when a child is treated with cruelty.

Eastwood tells the story in unexpected ways. The way Butch starts right out, for example, letting Phillip hold a gun. (But not to shoot someone with it; his reasons for doing this, in fact, are so deep that you have to think long about them.) And scenes of quirky humor involving runaway trailers, Halloween masks, barbecued steaks and other details that break the tension with a certain craziness.

(There is, for example, a scene in a roadside diner named “Dottie’s Squat and Gobble,” which is the best restaurant name I have ever seen in a movie.) “A Perfect World” has the elements of a crime genre picture, but the depth of thought and the freedom of movement of an art film.

You may be reminded of “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Badlands” or an unsung masterpiece from earlier in 1993, “Kalifornia.” Not because they all tell the same story, but because they all try to get beneath the things we see in a lot of crime movies and find out what they really mean.