Since I saw “The Social Network” Friday and filed my first post about it, I’ve had a chance to read what some other people are saying. Some most intriguing angles, and all of them more or less valid. My take was that it’s a movie about codes of communication. At Time Out, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin said he thought of it as a movie “about a guy who is an antihero for the first hour and 55 minutes of the movie and a tragic hero for the final five minutes of the movie.” Matt Zoller Seitz offered a way of reading it as a horror film, and led me to Richard Brody, who compares it to “Amadeus” (with the Winklevii as Salieri) and interprets it as a new media tale of outsider entrepreneurs and Jewish assimilation, along the lines of Neal Gabler’s book about the original movie moguls, “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood.” (That book is essential reading for lovers of American movies, by the way.)

Harvard Law professor and “free culture” advocate Lawrence Lessig comes at “The Social Network” from a legal perspective:

… as I watched this film, as a law professor, and someone who has tried as best I can to understand the new world now living in Silicon Valley, the only people that I felt embarrassed for were the lawyers. The total and absolute absurdity of the world where the engines of a federal lawsuit get cranked up to adjudicate the hurt feelings (because “our idea was stolen!”) of entitled Harvard undergraduates is completely missed by Sorkin. We can’t know enough from the film to know whether there was actually any substantial legal claim here. Sorkin has been upfront about the fact that there are fabrications aplenty lacing the story. But from the story as told, we certainly know enough to know that any legal system that would allow these kids to extort $65 million from the most successful business this century should be ashamed of itself. Did Zuckerberg breach his contract? Maybe, for which the damages are more like $650, not $65 million. Did he steal a trade secret? Absolutely not. Did he steal any other “property”? Absolutely not–the code for Facebook was his, and the “idea” of a social network is not a patent. It wasn’t justice that gave the twins $65 million; it was the fear of a random and inefficient system of law. That system is a tax on innovation and creativity. That tax is the real villain here, not the innovator it burdened.

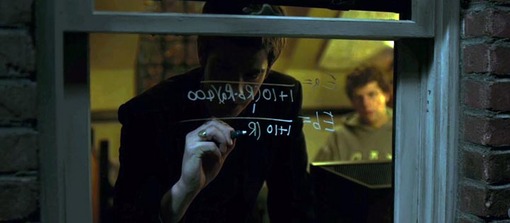

Perhaps Sorkin missed the absurdity Lessig cites, but the movie doesn’t. These observations lead me back to the primacy of code (in fact, Lessig wrote a famous Harvard Magazine article in 2000 called “Code is Law“) in interpreting “The Social Network.” The movie’s Mark Zuckerberg is immature, awkward, arrogant, rude, defensive, solipsistic… but he is gifted with the sharp analytical intelligence of a good developer. As I said previously, he is able to translate ideas into executable code, applications that people can actually use. And they like using it. They say they get “addicted” to it.

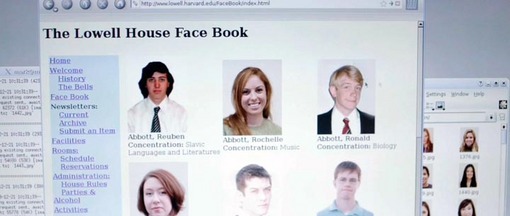

The Internet is largely an open source concept — giving people tools to do things. For every proprietary technology (whether it’s Microsoft Internet Explorer or Adobe Flash) there are an increasing number of free, open-source alternatives that work just as well or better (and that are compatible with other popular technologies). Which is what makes the lawsuit of the Winklevii — in the movie, at least — as Lessig says, “absurd.” The idea of an online face book wasn’t theirs to begin with (not that it would matter, but the point is made that Harvard had been trying to do it for years, hampered by typical institutional inertia). Dating software like Match.com (1995) and eHarmony (2000) had been around for years — and social networking sites like MySpace (2003) and Friendster (2003) were already live by the time Facebook came along. The “invention” is not the idea; it’s the execution, the whole package translated into code and presented, in the argot, as a “user experience.” ¹

That, I’d argue, is exactly what Mark is saying when he tells the Winkelvii, “If you guys had invented Facebook, you would have invented Facebook.” He didn’t steal their ideas, or their code — but it wasn’t very nice, or ethical, to stall them while he was working on a competing (though much more ambitious) product. Likewise, he definitely screwed over his friend Eduardo Saverin by diluting his stock — even though he was allowed to do so under the agreements Saverin himself signed but did not read. Complicating matters further, Saverin was under the impression that the lawyers presenting him with the Facebook documents were working on his behalf. Everything about this movie — especially Mark himself — is cast in moral/ethical shades of gray… or murky dark brown.

No one’s motives are clear, or uncomplicated, and nothing is resolved at the end of the picture. There’s a through-line that suggests Mark was driven by an outsider’s social ambition and the desire to either impress or get back at or get back together with a girlfriend who dumped him (or all of the above). But because the movie is constructed from other people’s memories and sworn affidavits and depositions (The Accidental Billionaires, the Ben Mezrich book on which the film is based, was written with the cooperation of Eduardo Saverin), most of what we see is somebody’s subjective version of events, or someone’s imaginative reconstruction of what might have happened.

And Mark Zuckerberg (as played by Jesse Eisenberg, written by Aaron Sorkin and directed by David Fincher) remains the central enigma, the code that can’t be cracked.²

* * * *

¹ Footnote: Not that it’s any excuse, but everybody knows how Microsoft was founded: Bill Gates told IBM that he’d written an operating system for PCs. He then went out and bought one from Seattle Computer Products, which he quickly polished, then turned around and licensed to IBM and other 8086 PC makers, and made a fortune. SCP eventually sued Microsoft for not revealing that IBM was interested, and the suit was settled for $1 million. In my time at MS, in the mid-1990s, people used to joke that the company produced more lawsuits than code. It’s an ugly business, software. Maybe they all are.

² As icily vicious as the movie’s Mark can be, I honestly can’t blame him sometimes. Do you know how frustrating it can be to try to communicate with a group of otherwise intelligent people (like, say, the lawyers in the movie) who think they know something about what you do, but don’t have a clue? They can get awfully arrogant and condescending — while having no clue about how dense they are. I know next to nothing about writing code, but I know it exists and I understand why it is necessary. Try explaining to somebody who doesn’t understand the web that this page you’re looking at right now is built from many lines of code interacting with each other and pulling/serving information and graphics from various servers all over the world. Most of the page does not, in fact, even exist until you bring up the URL. Using the View Source command in the browser menu, here’s what one part of one (HTML) dimension of this page REALLY looks like: