A year ago, I would not have believed that institutions I considered impenetrable to a fault would collapse like a house of cards from the slightest push by the Trump administration. Television networks, big law firms, major universities with multi-billion-dollar endowments, giant corporations with top lobbyists who have been successful at getting all kinds of subsidies and loopholes—all of them have caved to a shocking degree.

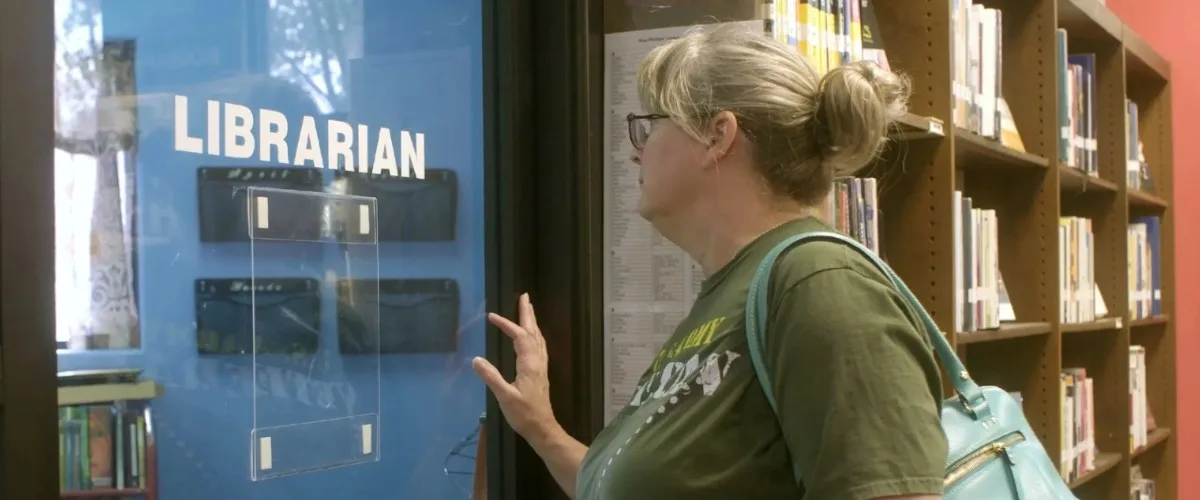

But unsurprisingly, I knew I could count on one group to be fearless, baddest-of-badass warriors for the public good: school and public librarians. As the sister of a librarian and the proud patron of four different library systems, including the Library of Congress, I know that public libraries are not just one of our greatest treasures but a foundational resource for democracy. They are on the front lines of freedom because they represent freedom of thought. Interviews with librarians and harrowing footage of school board meetings reveal how school libraries have become “battlegrounds for a political war,” with making books available even being considered a criminal act. Of the 40 librarians working in one such community, 20 were fired or pushed out.

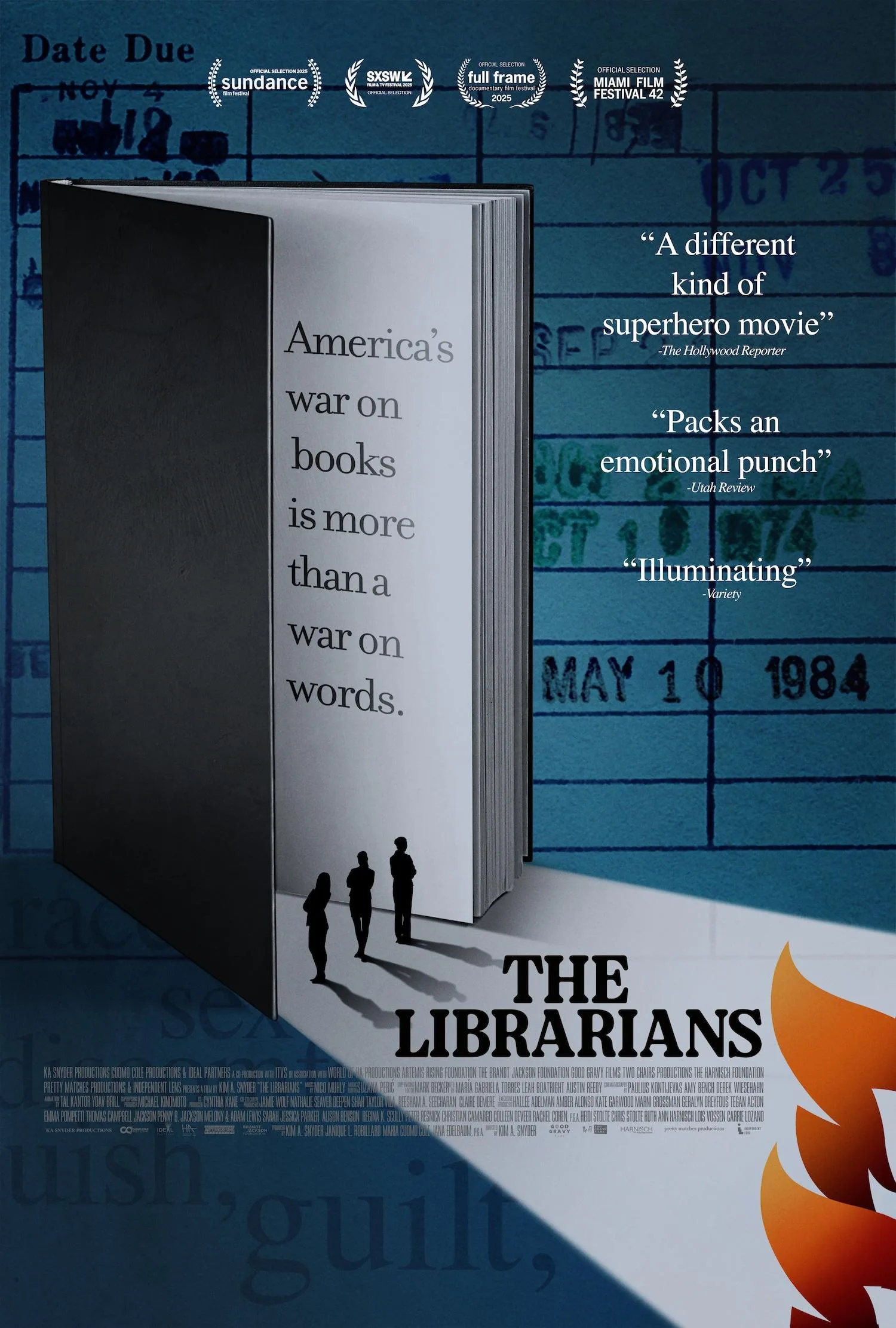

“The Librarians” is a documentary about the hysterical, unfounded, personal, and sometimes violent attacks on librarians. It is also about their unwavering commitment to making facts, literature, and inspiration available to anyone. Director Kim A. Snyder (“I Remember Me”) presents the film in a traditional documentary style, featuring interviews and archival footage, with minimal intrusion from the filmmakers. However, a witty opening credit sequence showcases their affection for iconic library spaces.

The book-banning attacks, funded and fueled by donors who refuse to reveal themselves, weaponize outrageously inflammatory language to accuse librarians of the most appalling of crimes: “pornography,” “pedophilia,” and “grooming” with hyperbolic rhetoric about “the radical left.” The book banners do not just ask that their own children be prevented from seeing those books; they do not want any child seeing them, no matter what the parents say.

An anonymous librarian, her image obscured to protect her from harassment, discusses the list of 850 books in a letter sent to Texas school superintendents by then-state legislator Matt Krause. He asked how many copies there were and what they cost. There was no information about who prepared the list or what was objectionable about each book. There was vague language about any other books that “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.”

The list includes many acclaimed, popular, and classic books that feature historical material about racism and factual portrayals of some controversial topics related to race and gender. School librarians, who have extensive training in child development and pedagogy, are knowledgeable about reading and maturity levels as well as community standards. All books are selected based on age appropriateness. For example, a picture book about a Black girl loving her hair might be suitable for kindergarten through third-grade libraries. In contrast, middle and high school libraries might have books available on the Civil Rights Movement, the Holocaust, or puberty.

A librarian points to one of the children’s picture books on the list, And Tango Makes Three. It is based on the true story of two male penguins in the Central Park Zoo who adopted an abandoned egg and raised the chick. There is no mention of sexuality or a sexual relationship in the book, but its portrayal of a male pair has made it a regular on the most-banned list. For high school students, Krause’s list includes books about the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, the forced displacement of Native Americans known as the “Trail of Tears,” How to be Antiracist, and Beyond the Gender Binary, and even an “anti-woke” book about “how activist scholarship made everything about race, gender, and identity–and why this harms everybody.”

The film has some indelibly searing moments, linking these efforts to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare, to Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels’ burning books by Jewish authors, and to the Twilight Zone episode “The Obsolete Man,” with Burgess Meredith as a librarian sentenced to death. There is a quote from President Eisenhower: “Don’t think you’re going to conceal faults by concealing evidence they ever existed. Read every book.”

We hear from Steven Pico, who in 1976, when he was a high school junior, challenged the banning of books in his school library all the way to the Supreme Court, from the daughter and wife of Baptist ministers, who was fired from her librarian job over a book controversy, and from Amanda Jones, author of That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America. A member of the school board who ran on a platform promising a thorough inspection of curricula admitted, after her review, that there was nothing inappropriate, and the book banners attacked her. We see library shelves covered over with paper or crime scene tape. And we see students protesting the attacks on books they want to read.

The heart of the film lies in the librarians, who view the libraries as “this magical entry point to the world, to stories, to ideas.” Their courage and integrity are bracing, and it is a delight to see one of them relish their superpower—“Research!”—to learn more about the people and money behind the book banners. They know, as one of them says, that the libraries are just the first step in attacks on the school system, public libraries, and access to independent, non-state-approved sources of information. As Steve Bannon says in an archival clip, “The school board is the key that picks the lock.”

The film’s most unforgettable scenes show a furious Monica Brown speaking at a school board meeting. Although she homeschooled her eight children, she served on the public school district’s book review committee and suggested that a Christian pastor should decide what books should be in the public school’s library. Her oldest son, Weston Brown, who is gay, spoke in opposition at a subsequent session, his mother seated behind him but refusing to look at him or talk to him, even outside the building after the meeting.

This is not about politics. It is about trust. We should trust the people who trust us to tell truth from propaganda, not the people who think we must be “protected” from challenging ideas. If we limit library books to those that don’t make anyone feel discomfort or distress, all that will remain will be Pat the Bunny and Goodnight Moon. Dictionaries, atlases, the Civil War, any war, science, Shakespeare, and even the Bible will be locked away.

At a time when elected officials are telling us that January 6 insurrectionists were FBI plants, that acetaminophen causes autism despite extensive documentation to the contrary, and where the President puts an AI fake of himself on social media as though it was an official announcement, this movie reminds us there is just one way to separate truth from propaganda: learning. As Janet Jackson put it, “We are in a race between education and catastrophe.”