It’s nothing short of ominous that a film like “Happyend” is opening in the U.S. the same week that the Supreme Court ruled ICE agents can now legally profile people based on their physical appearance, the language they speak, or any other characteristic they deem makes someone suspect of being undocumented. Carrying proof of citizenship or legal status may now become the norm for anyone who doesn’t fit the rigid mold of American whiteness.

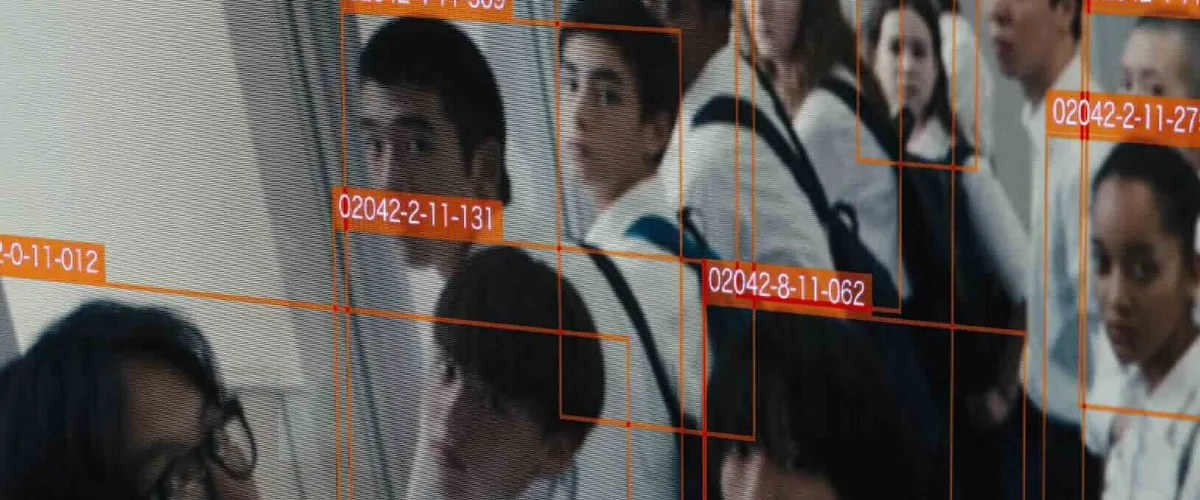

Halfway through the first fiction film from writer-director Neo Sora, son of the late beloved composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, a scene seemingly ripped from our headlines occurs. Kou (Yukito Hidaka), a Japanese-born teenager of Korean descent, is stopped by the police. In this near future, law enforcement can simply point a cell phone at a detainee and, via face recognition technology, their information becomes instantly available. Policemen now know Kou is not a Japanese citizen, because despite his family having lived in Japan for four generations, the government still treats them as nefarious foreigners who can’t easily become naturalized. The officers demand that he show his residency card. Kou argues he is not obliged to carry it around. Unable to produce the document, he’s taken away to get it.

The disturbing transgressions of a surveillance state and the ways fascism co-opts real concerns about collective safety to further encroach on people’s freedoms are central to Sora’s propulsive, unsettlingly timely, and ultimately endearing coming-of-age drama. Yet, these latent sociopolitical preoccupations only gain gravitas because they are addressed through the lens of the evolving friendship between Kuo and Yuta (Hayato Kurihara), lifelong pals living in Tokyo with dreams of making electronic music.

On the cusp of adulthood, and conscious that his ethnic background makes him a target, Kou decidedly takes an interest in activism. A new surveillance system at their high school can not only determine who a student is as soon as they step into the view of a camera, but it also makes judgments about their behavior. What’s happening in the microcosm of their educational institution mirrors society at large, with Prime Minister Kito expanding the military’s unchecked power under the pretense that a major earthquake might soon strike, and order must prevail.

“That tyrant is faking an emergency to try and run a dictatorship,” says Fumi (Kilala Inori), a politically involved student, about the fictional leader—a statement that anyone in the U.S. could utter today with equal validity. But rather than harp on the crimes of authoritarians, Nora opts to champion the idealism of the youth who still believe that change is attainable, that not all is lost.

At once a cautionary tale about a reality thinly distanced from ours and a welcome breath of hope, “Happyend” tracks Kou becoming increasingly disappointed in Yuta, and how the latter, reluctantly at first, begins to understand that one shouldn’t coast by oblivious to the world’s injustices, especially when they directly impact the people we love. And these rowdy teenage boys, who revel in pranking adults and playing music till sunrise, hold profound brotherly affection for one another, which is tested not only in the ways that growing up naturally either pushes us closer or separates us from people we thought we knew, but by the macro circumstances of the time period they are existing in. Hidaka’s eager-eyed Kou moves with a tranquil assertiveness that complements and then clashes with the perpetual cheekiness with which Kurihara plays the unserious Yuta.

Released in Japan late last year, “Happyend” may have preemptively addressed the anti-immigrant sentiment that has been vocalized in the form of protests in the Asian country over recent weeks. That the other adolescents in Yuta and Kou’s tight-knit friend group appear handpicked to represent the racial, ethnic, and ideological diversity of Japan, a subject not often depicted in the national films, feels narratively contrived, though thematically purposeful. Ming (Shina Peng), the only girl in the group, is of Taiwanese descent, while mixed-raced Tom (Arazi), is the son of a Black American father, and Ata-chan (Yûta Hayashi) expresses his individuality defying the school’s dress code. Even if secondary to the conflict arising between Yuta and Kou, each of these characters offers insight into the experience of being perceived as different from the norm. That Sora is an American-born and educated artist may in part explain his interest in a heterogeneous ensemble.

Sora and cinematographer Bill Kirstein, who previously collaborated on the director’s portrait of his father “Ryuichi Sakamoto: Opus,” here shoot certain interactions from afar as if their camera acted as another surveillance device, observing how the characters move through their lives with a magnifying glass. The film’s playful visual grammar extends to the editing (a freeze frame near the end rekindles the boys’ banter after their schism), and contrasts with Lia Ouyang Rusli’s hypnotic score that comes in potent sonic waves. In turn, Sora handles the near-future aspect of the story with a measured hand. Instead of prevalent screens, comments about how obsolete printed books or applications seem to these young people illustrate that their worldview differs from ours, even if still beholden to our old ways.

Throughout “Happyend,” an earthquake alert rings like a recurrent motif. Rather than warning the population about an impending natural disaster outside of their control, the message seems closer to a call to action to shake people out of their complacency. For its lucid interpretation of the current global moment without surrendering to paralyzing despair, “Happyend” settles among the most unmissable films to hit U.S. theaters this year. “What comes after?” Kou asks Fumi and another activist about what it will all look like if the protests change everything for the better. The answer, hopefully, will reference the movie’s idyllic title, or something closer to it than where we find ourselves today.