Reading Arash Azizi’s fascinating Shadow Commander: Soleimani, the US, and Iran’s Global Ambitions recently, I was reminded of the large part that executions played in both the creation and the continuation of the Islamic Republic of Iran. When Iran’s 1979 Revolution occurred, the primary goal shared by many segments of Iranian society was simply the overthrow of the country’s monarchy, and the possibilities for a new form of government were myriad. But when the forces favoring an Islamic state consolidated their grip on power, they maintained it with wave after wave of executions that wiped out communists, dissidents, secularists and many others, even the makers of films considered pornographic.

The executions continued after the regime’s rule was firmly established, even while Iran suffered hundreds of thousands of deaths during the prolonged agony of its war with Iraq in the 1980s. In the following decade, a new form of quasi-execution emerged; called the “Chain Murders,” these involved scores of writers, intellectuals and activists being brutally slain by shadowy government operatives, deaths that not only silenced important regime opponents but also served as bloody warnings to all of Iran’s liberal intelligentsia.

Ironically, these late-‘90s killings happened even as Iran’s government-sanctioned cinema was gaining international renown through the prize-winning films of Kiarostami, Makhmalbaf, Majidi, Panahi and others. Would such an artistic surge not eventually collide with the darker forces in the government facilitating it? One very potent answer to that question came in Mohammad Rasoulof’s “Manuscripts Don’t Burn,” a 2013 drama that devastatingly fictionalized some of the Chain Murders. Reviewing it here, I called it “easily the most daring and politically provocative film yet to emerge from Iran.”

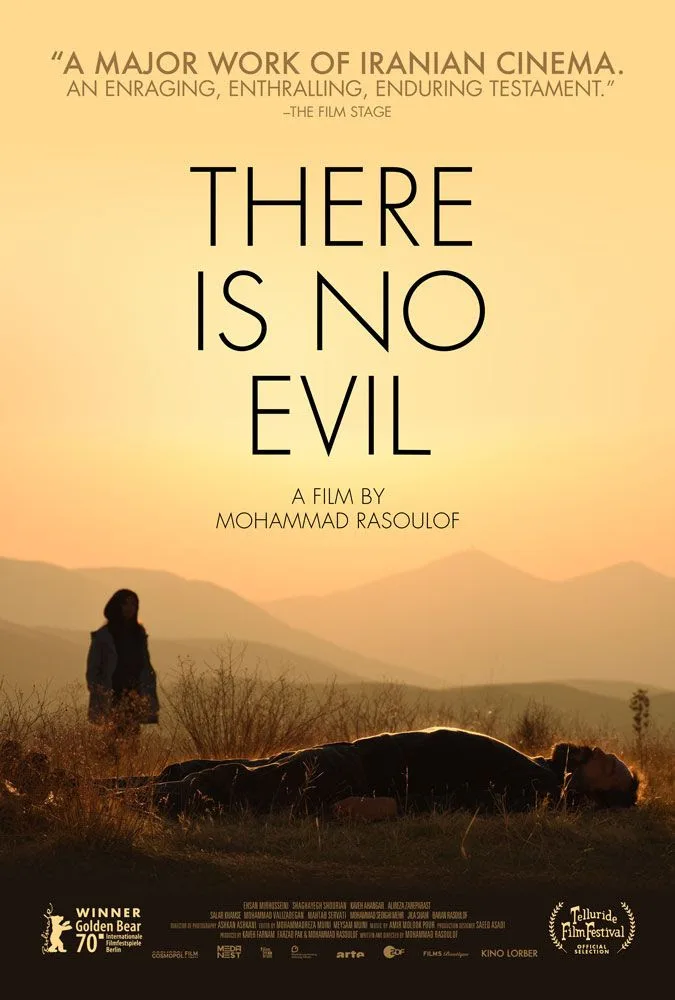

With his newest film, “There Is No Evil,” which won the Golden Bear at the 2020 Berlin Film Festival, Rasoulof mounts another fierce assault on the practice of state-sponsored murder in Iran, which in recent years has regularly trailed only China in the number of executions it stages annually. Told in four separate stories, the film offers different angles on various people who participate in the official killings, refuse to, or are affected by them. But don’t go into it expecting a stark, obvious broadside. More parable than polemic, “There Is No Evil” weaves a rich, engrossing artistic tapestry that interrogates a number of the psychological, moral and cultural dimensions of executing people. It is, in fact, so much not a standard “issues film” that I even hesitate to say it is “about capital punishment.” Better, perhaps, to say that it’s a determined probe into the soul of a nation that permits so much legal bloodshed.

Although many executions in the immediate post-Revolutionary period were accomplished by firing squad, hanging has been the preferred mode of dispatch in recent years. While the government occasionally stages outdoor executions in which those convicted of especially heinous crimes are hanged from large cranes in public squares, most executions happen behind prison walls, where those doing them—sometimes the victims’ family members—do so by “pulling the stool” from under the convict who stands on it with a noose around the neck.

In the quartet of tales that comprise “There Is No Evil,” no attention is given the guilt or innocence of the parties to be executed; the corruption of the religiously-based Iranian justice system that often precludes fair trials or sentences the innocent to die could be the subject of another film. Instead, Rasoulof focuses closely on people who, in one form or another, face the challenge of “pulling the stool.” The first story, also called “There Is No Evil,” is a minor masterpiece that could stand alone as a brilliant short distinguished by a stunning final minute. In it, we watch as a middle-aged, seemingly ordinary middle-class guy named Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini) retrieves his car from an underground parking garage in the very early morning, then goes about a daily routine that includes exchanges with his wife, caring for his mother-in-law, picking up his daughter at school, and having an argument at the bank. Thanks to Rasoulof’s skills, these scenes are wonderfully well-observed and involving. It’s only when the day comes to an end, and Heshmat returns to work, that we register the shock of seeing how he supports his family. It’s a moment that casts pall over everything that follows.

The remaining three stories concern people who are obliged to kill, rather than choosing to. The second, “She Said, ‘You Can Do It,’” calls to mind an American prison drama of the ‘50s, with the grit and tension a Samuel Fuller might have brought to it. Six young soldiers in a bleak military cell argue over the terrible choice facing one of them. Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar) has just begun his mandatory two-year military service when he’s ordered to execute a prisoner by hanging. His conscience struggles mightily against the command, but if he refuses it, he will sacrifice his dream of moving abroad with his girlfriend. The conflict is agonizing, the controversy among the soldiers heated and variegated, and Pouya’s eventual decision gives the episode the surprise and desperate momentum of a thriller.

The next episode, “Birthday,” establishes a tone that’s more lyrical, even romantic, than what has come before. Set in a lushly forested part of northern Iran, it begins with a young man named Javad (Mohammad Valizadegan) stripping off his clothes and bathing in a river; it’s an unusually sensual act for an Iranian film, and one that seems to suggest Javad’s need for ritual purification. He’s a soldier on a three-day leave, and we soon see that his goal involves reaching Nana (Mahtab Servati), the girl he wants to marry. But Javad has faced a choice like the one Pouya faced and taken a different route, one that has given him a moral burden that threatens to undermine everything that he hopes to build in life.

The film’s final episode, “Kiss Me,” suggests how such burdens can extend over generations, entailing secrets and guilt that poison and deform the lives they touch. Darya (Baran Rasoulof, the director’s daughter) is a bright young medical student who has lived in Germany since childhood and arrives in Iran to visit her father’s brother, Bahram (Mohammad Seddighimehr), and his wife, Zaman (Jilla Shahi). Though the couple were apparently once established professionals, they now live a secluded life in the remote countryside, where they keep bees and deal with the predations of nature: they had chickens till too many were killed by foxes, they tell Darya, then they got a dog to protect against foxes but it was killed by wolves. This cycle of violence amid animals seems to mirror a socially decreed one among humans, a practice that has given Bahram a secret he struggles to tell his niece.

The pleasures of watching “There Is No Evil”—a title that grows more piercingly ironic as the film progresses—are considerable. Rasoulof’s skills as a director have grown throughout his 20-year career, and he and cinematographer Ashkan Askkani give the film great visual nuance and richness that are especially impressive in the very different outdoor settings of the third and fourth episodes. However, multi-episode films often suffer when one or more parts fall short of the others, and “There Is No Evil” doesn’t escape this problem: Its fourth episode is overlong and confusing, lacking the clarity and narrative coherence of the previous parts.

That flaw notwithstanding, the film is a powerful work of moral courage and urgency. Since Rasoulof and Jafar Panahi were arrested while working on a film about 2009’s controversial presidential election in Iran, they have both been encircled by various kinds of official harassment including prison sentences (so far not enforced), bans on filmmaking and giving interviews, and having their passports confiscated. Yet both directors have gone on working in defiance of all the official censure and obstruction, turning out films that win acclaim around the world while remaining banned in Iran. Their extraordinary efforts demonstrate the amazing tenacity and resilience that keep Iranian filmmakers at the forefront of world cinema.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.