Watching Mohammad Rasoulof’s riveting “Manuscripts Don’t Burn,” easily the most daring and politically provocative film yet to emerge from Iran, I was reminded of something I heard when visiting that country to study its cinema in the late ‘90s. When I asked an Iranian cinephile the difference between Iran’s artistically vital but little known cinema of the 1970s and its successor, which gradually captured the world’s attention following the 1979 Iranian Revolution, he smiled and said, “In the post-revolutionary cinema, there is no bad guy.”

The remark was both droll and apt. Films before the Revolution often conveyed a pervasive sense of bitterness and discontent, a mood ultimately—if always implicitly—traceable to one paramount bad guy: the Shah, whose overthrow was supported by the vast majority of Iranians. Iranian films of the ‘80s and beyond, by contrast, frequently projected the buoyancy of a culture reinventing itself, even when dealing with harsh social problems or reflecting the content restrictions of the Islamic Republic. When elements of discontent did reemerge, in films such as Abbas Kiarostami’s “Taste of Cherry,” Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s “A Moment of Innocence” or Jafar Panahi’s “The Circle,” the targets were usually—and again, implicitly—cultural structures and the regime generally rather than individual miscreants.

With “Manuscripts Don’t Burn,” though, the bad guy returns to Iranian cinema with a vengeance—and in triplicate, no less. Based on real historical events, Rasoulof’s drama focuses on two operatives assigned to terrorize, torture and murder dissident writers and intellectuals. These guys go about their dirty business with a methodical, unemotional brutality, but they are simply repression’s foot soldiers. Far more chilling is their superior, a young guy who works in an office, wears fashionable clothes, and seems to have no qualms about advancing his career by killing former friends.

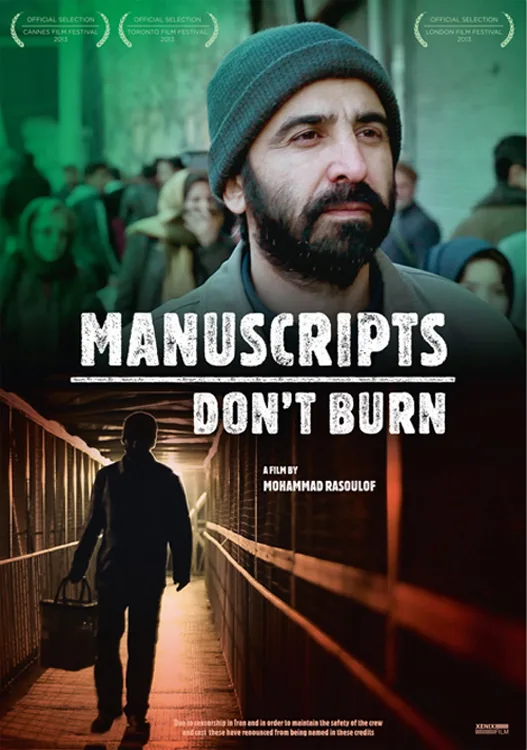

The film has the fraught mood if not the adrenaline pace of a thriller. We first see Khosrow and Morteza (no names of cast or crew are given due to the film’s perilous political nature) as they are leaving a job. With characteristic subtlety, Rasoulof doesn’t show us the killing, only that Khosrow has a man’s bloody hand print on his neck—a grisly detail that’s somehow more unsettling than explicit violence would be.

Tense and drawn, Khosrow wants their next stop to be an ATM. He needs payment for his mayhem because he has a little boy who requires an operation. But an even greater problem may be his wife, who complains that their son’s affliction is punishment for his work. Khosrow’s worry over this charge at least shows the flicker of conscience. Morteza, a stolid and unreflective assassin, shrugs it off, saying that their assignments are in accordance with shariah—the very rationale that allows extremist elements in a government supposedly based on religion to slaughter their opponents without compunction, after branding their thought as deviant and foreign-influenced.

Rasoulof interweaves the killers’ movements with the actions of certain men who will soon be their targets. They are old and, in one case, infirm, and though they understand their situation well enough to be afraid, their spirits are still defiant. One has a manuscript that recalls an incident some years before when the security apparatus tried to murder a group of writers by driving their bus off a cliff (this is evidently based on an actual incident from 1995). It is this manuscript that is the target of the two killers’ superior, a man who seems to combine the worst of medieval theocracy and modern technocracy. The book implicates him, a former dissident turned hardline functionary, so his motives are both nakedly self-serving and cold-bloodedly treacherous.

In his striking earlier films, “Iron Island” and “The White Meadows,” Rasoulof deployed a distinct version of the visual lyricism and quasi-mystical symbolism of other Iranian films. “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” offers no such cinematic poetry. It is bluntly literal, almost shockingly so given the context. Rather than other Iranian films, its chilly, muted colors, claustrophobic framings and understated performances by an excellent cast recall ‘70s American suspensers such as “The Conversation” and “Klute.”

Like other Iranian directors, however, Rasoulof doesn’t care about genre mechanics or conventional narrative arcs. Judged by some standards, the film’s last third could use greater dramatic torque and deeper thematic probing. But this is not a standard political thriller. It is an unprecedented statement and damning analysis, an X-ray of not only the toxic political and personal motives that underlie the current regime’s murderous assault on dissent, but also of a society polarized between educated cosmopolitans on one side and often illiterate and credulous regime-supporters on the other.

The kinds of killings depicted in the film appear to be based on the “Chain Murders,” in which roughly 80 Iranian intellectuals were murdered between the late ‘80s and 1998. Rogue hardliners in the security apparatus were supposedly responsible, but though several individuals were tried and convicted of the crimes, their actual provenance and perpetrators remain murky and much-debated.

The film, however, has a contemporary setting, and the anger that fuels it perhaps dates back most directly to 2009, when the Iranian government brutally suppressed protests over a presidential election that many felt was fraudulent. Rasoulof and Panahi were the two most prominent filmmakers associated with the opposition, and both were arrested, tried on trumped-up charges and given draconian sentences of prison time and banishment from filmmaking for many years. The prison sentences, though, have yet to be carried out, and both filmmakers have gone on making films in secret to be smuggled out of the country. (The exteriors of “Manuscripts Don’t Burn” were reportedly shot in Iran, the interiors in Germany, where Rasoulof has been permitted to travel.)

Borrowing his film’s title from a famous phrase in “The Master and Margarita” by Soviet dissident Mikhail Bulgakov, Rasoulof no doubt means to encourage a comparison between the dissident artists of the ex-USSR and Iran’s filmmakers today. But there are also important differences. Under Stalin, artists like Rosoulof and Panahi would have been quickly executed or permanently disappeared to Siberia. In today’s Iran, on the other hand, their situation is more like Ai Weiwei’s in China: they are too prominent to eradicate completely, yet their continuing obstreperousness makes them targets of constant official harassment and hostility.

In bringing “the bad guy” back into Iranian cinema, Rasoulof has done something that Iranians will instantly recognize: drawn a comparison between the Shah’s regime and the present one. Whether he will ever be allowed to work in Iran again, secretly or not, is very much in doubt, but the bravery shown by him and other Iranian artists in recent years will continue to serve as an example to those battling repression the world over.