“Lone Samurai,” a Japanese-language movie written and directed by California-raised filmmaker Josh C. Waller, begins with on-screen text and a Japanese voice-over reading about the 13th-century invasions of Japan led by the Mongolian Kublai Khan, the marauder whose eventual mansion-building skills would centuries later inspire Charles Foster Kane. The point of the anecdote is to clue the viewer in to the origin of the word “kamikaze.”

The movie’s protagonist is not seen but instead heard as he and his samurai brethren slaughter the crew of a Korean ship. Yes, even back in the twelfth century, the beef between these two nations was strong. But then: shipwreck. Our lone samurai is washed up on an island with a wooden portion of the ship sticking out of his thigh. That’s gotta hurt, and it does, and our man pulls the sort-of plank out of his flesh and tries to heal up. Once he feels a little better, he determines to end it all. He constructs a makeshift shrine at which he intends to commit seppuku, that is, ritualistic suicide by disemboweling, with one’s sword, of course.

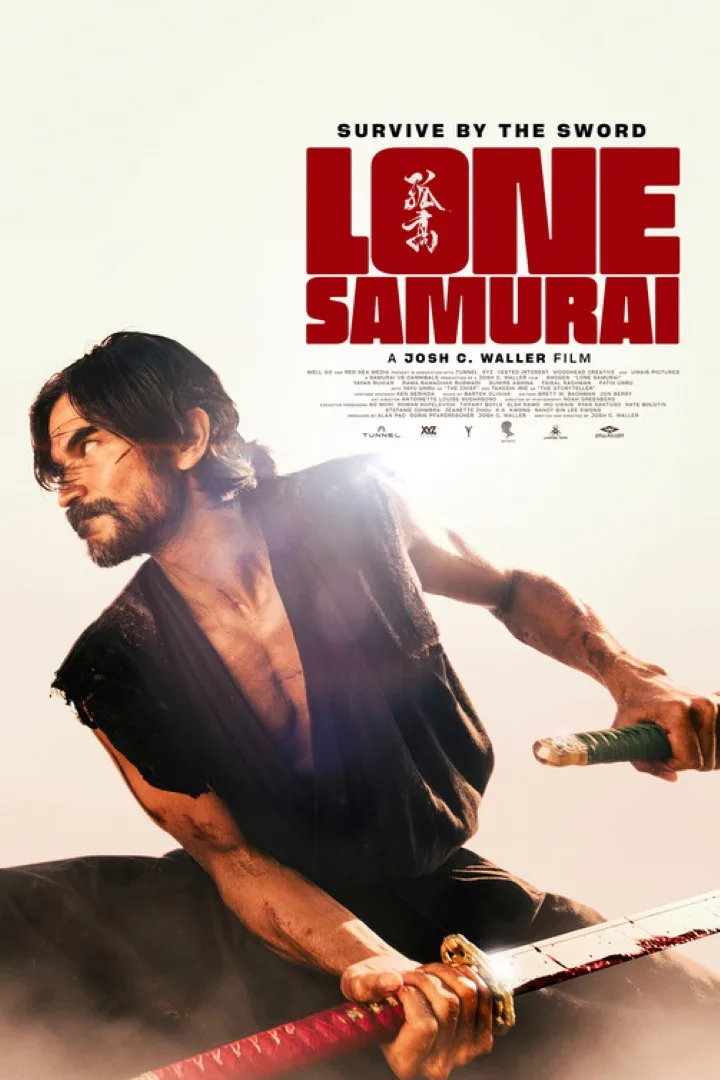

But. Praying at that makeshift shrine, he reflects, “Pain kept me alive.” And he gets turned around. But it’s a good thing that what kept him alive was pain, because now he is going to have to endure a lot more of it. Played by the Japanese action veteran Shogen, this title character is soon besieged by the island’s natives, short, sometimes squat, face-painted cannibals.

Filmmaker Waller is here trying to have things both ways: to pay a sincere tribute to the classic Japanese samurai movies in the widescreen frames and spurting blood it borrows, and also to make a genuine thing, a samurai qua samurai picture. He eventually gets there, or almost does. For as furious and grisly as the fighting becomes, the groundwork that establishes exactly what’s at stake is not entirely convincing.

Riku (for that is how he is addressed) has frequent flashbacks to his life before battle—his wife, his children, and so on. They don’t really make an impression as such because they’re clearly not things he can recover. And all things considered, he’s entirely better off keeping his eye on the ball, or rather, on the severed heads that his cannibal antagonists keep showing him, lest he become one of their number.

Waller is blithely, glibly, even unconcerned with the politically retrograde move of having Indonesian performers play the cannibals. He’s clearly having too much fun with those aforementioned widescreen frames that, for all his effort, he can’t construct as beautifully as Kurosawa did. The picture also lacks Kurosawa’s humor. And if Shogen doesn’t have Toshiro Mifune’s charisma, it can’t be blamed on him; who really does, after all? But the movie does have enthusiasm, undeniably. But what it’s ultimately best at is whetting one’s appetite for a re-viewing of “Sanjuro,” or “Yojimbo,” or “Lady Snowblood,” you get the idea.