You know those little color strips you see in wall racks in stores where paint is sold? They’re keys to unlocking Pantone Color Systems, which brought a globally consistent way of identifying fine graduations of color into a world that had previously been fragmented and inconsistent, and assigning each hue a playful name like sea mist, lavender fog, or papaya punch.

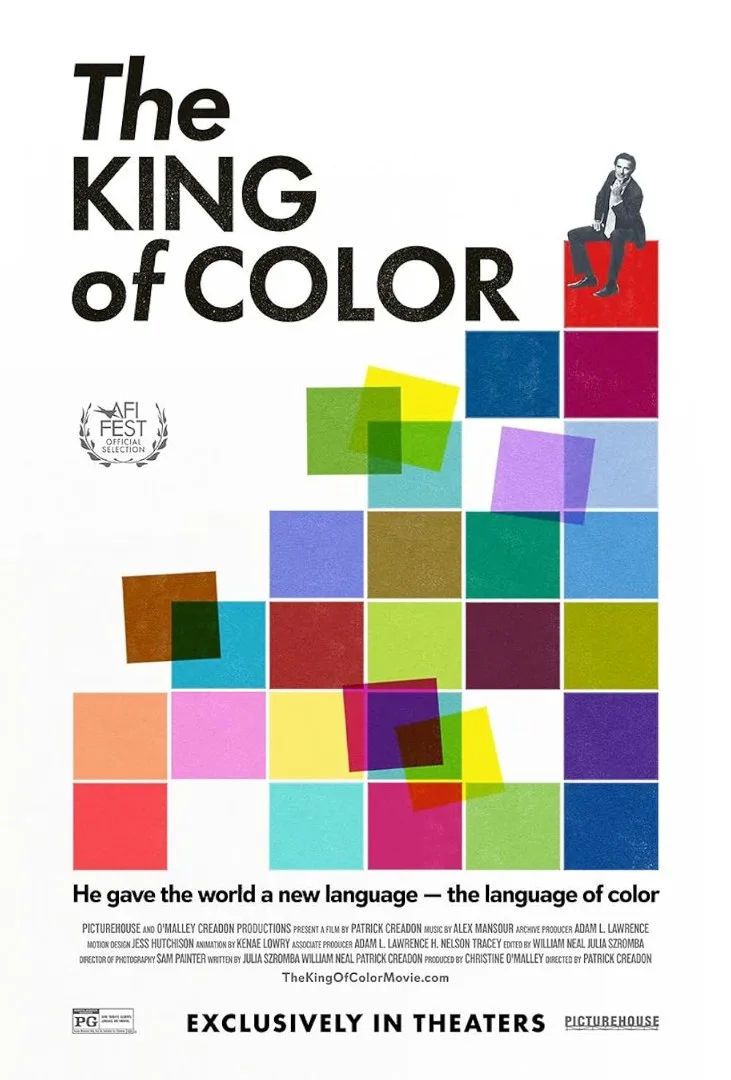

The man who invented it, 96-year-old Lawrence Herbert, is the subject of a documentary, “The King of Color,” from the makers of the popular “Wordplay,” about the creation of the New York Times crossword puzzle. It’s a character study that doubles as a first-person account of the evolution of color printing technology in the 20th century. It focuses on Herbert’s techniques for creating a staggering array of hues and devising precise formulas for color combinations that would always yield the same result, no matter who followed the instructions.

The above description might make “The King of Color” sound dry and super-technical, and the movie is definitely granular in its explanations. Luckily, director Patrick Creadon and producer Christine O’Malley (a husband-wife filmmaking team) are experienced teachers. They know how to use animation, graphics, archival photos, and clips from other movies to make things (mostly) clear, although when it gets into the math part, liberal arts-focused viewers (like this writer, an English major who checked out of mathematics after algebra) might still have trouble keeping up.

Color printing predates the 20th century, of course. It’s hundreds of years old and has undergone many technological and procedural variations, from woodcuts, lithography, and screen printing to photographic reproduction and laser printing. But they all had one thing in common: if you asked any five printers to show you “red,” you’d be shown five slightly different colors, because they all had their own process for creating and assembling the raw materials and getting the result onto paper. Herbert’s great innovation was the split fountain press, which allowed for the printing of 28 colors simultaneously, in an array of thick parallel lines that resembled an extruded, hyper-detailed cousin of the color wheel.

Everybody everywhere uses Pantone systems now, because it allows everyone from fashion designers and magazine publishers to motion picture art directors and abstract painters to say “I need oyster gray, autumn blonde, moonless night, and cream gold” and be confident that collaborators in different locations can be convinced that they’re all in agreement on what they all look like. Herbert refers to the classification system as “a dictionary of color.”

You should know going into “The King of Color” that it’s a feature-length narrative equivalent of one of those official portraits that government officials, corporate executives, and other powerbrokers commission to hang in the foyers of their mansions. The project came about when Herbert decided in his mid-nineties that he wanted somebody to capture the story of his life and work while he was still lucid enough to be the storyteller. He says he did this mainly so he could have a Herbert-approved account he could refer people to, so he wouldn’t have to tell the same stories constantly. One of his adult children—a weird phrase for people who are probably in their sixties now—says, “I don’t know why he wants to tell his own story. It seems a little self-centered, frankly.”

Thankfully, the filmmakers who said yes insisted on having final cut, which lends a smidge of detachment in the movie’s production, even though the result is so affectionate and suitably impressed by Herbert that you wouldn’t be able to tell it’s not supervised by its subject unless somebody told you. Herbert’s recollection of key moments in his life comes across as self-serving and a bit hyperbolic, but no more so than most people’s accounts of their own daily lives, in which they always come across as the hero or the wronged party, and say witty things that their antagonists are too impressed to respond to.

Self-fluffing aside, the personal aspects of Herbert’s story are engrossing and sometimes moving, especially when he and family members talk about the midlife crisis that dissolved his marriage in the 1970s, and his experience as a soldier during the Korean War, which traumatized him so severely that he still won’t talk about it in detail. “Everybody who was there didn’t want to be there,” he tells the filmmakers. “The things that happened there, I don’t really want to resurrect.” The re-creations of Herbert’s first few decades of life rely on hand-drawn illustrations and old-school animation techniques, which subtly emphasize that what we are seeing is one man’s account, not necessarily the correct one.

It’s a smart, mostly light movie that will teach viewers a lot about processes they might not otherwise think about. You come away from the movie seeing the world in finer shades than when you went in.