“The Winslow Boy,” based on a play set in 1910, is said to be a strange choice for David Mamet, whose work usually involves lowlifes and con men, gamblers and thieves. Not really. This film, like many of his stories, is about whether an offscreen crime really took place. And it employs his knack for using the crime as a surface distraction while his real subject takes form at a buried level. “The Winslow Boy” seems to be about a young boy accused of theft. It is actually about a father prepared to ruin his family to prove that the boy’s word (and by extension his own word) can be trusted. And about a woman who conducts two courtships in plain view while a third, the real one, takes place entirely between the lines.

The movie is based on a 1940s play by Terence Rattigan, inspired by a true story. It involves the Winslow family of South Kensington, London–the father a retired bank official, wife pleased with their life, adult daughter a suffragette, older son at Oxford, younger son a cadet at the Royal Naval Academy. One day the young cadet, named Ronnie, is found standing terrified in the garden. He has been expelled from school for stealing a five-shilling postal order.

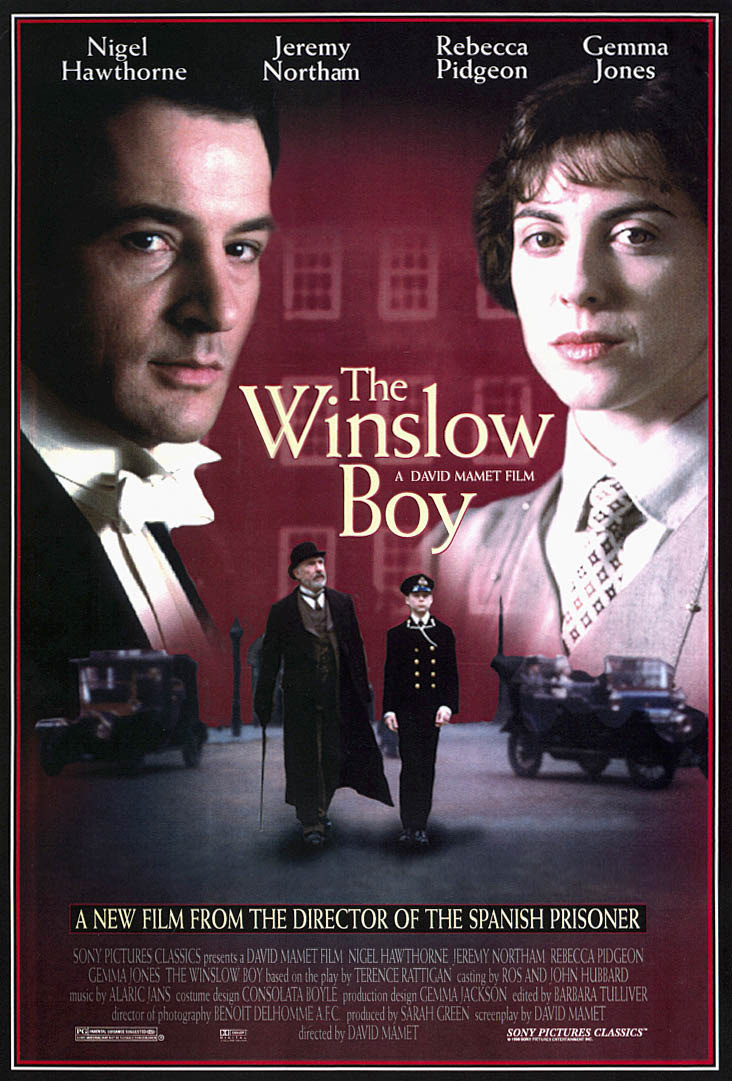

In a scene that establishes the moral foundation for the entire story, his father Arthur calls him into the study after dinner and demands the truth, adding, “A lie between us cannot be hidden.” Did he steal the money? “No, Father, I didn’t.” The father is played by Nigel Hawthorne (“The Madness Of King George“), who is stern, firm and on the brink of old age. He believes his son and calls in the family solicitor to mount a defense. Soon one of the most famous attorneys in London has been hired: Sir Robert Morton (Jeremy Northam), who led the defense of Oscar Wilde. The father devotes his family’s large but finite resources to the expensive legal battle, which eventually leads to the older son being brought home from Oxford, servants being dismissed and possessions being sold. Arthur’s wife Grace (Gemma Jones) protests that justice is not worth the price being paid, but Arthur persists in his unwavering obsession.

The court case inspires newspaper headlines, popular songs, public demonstrations and debates in Parliament. It proceeds on the surface level of the film. Underneath, hidden in a murk of emotional contradictions, is the buried life of the suffragette daughter, Catherine (Rebecca Pidgeon). She is engaged to the respectable, bloodless John Watherstone (Aden Gillett). She has known for years that Desmond, the family solicitor (Colin Stinton) is in love with her. As the case gains notoriety, John’s ardor cools: He fears the name Winslow is becoming a laughingstock. And as John fades, Desmond’s hopes grow. But the only interesting tension between Catherine and a man involves her disapproval of the great Sir Robert Morton, who rejects her feelings about women’s equality and indeed disagrees with more or less every idea she possesses.

It is an interesting law of romance that a truly strong woman will chose a strong man who disagrees with her over a weak one who goes along. Strength demands intelligence, intelligence demands stimulation, and weakness is boring. It is better to find a partner you can contend with for a lifetime than one who accommodates you because he doesn’t really care. That is the psychological principle on which Mamet’s hidden story is founded, and it all leads up to the famous closing line of Rattigan’s play, “How little you know about men.” A line innocuous in itself, but electrifying in context.

In a lesser film, we would be required to get involved in the defense of young Ronnie Winslow, and there would be a big courtroom scene and artificial suspense and an obligatory payoff. Mamet doesn’t make films on automatic pilot, and Rattigan’s play is not about who is right, but about how important it is to be right. There is a wonderful audacity in the way that the outcome of the case happens offscreen and is announced in an indirect manner. The real drama isn’t about poor little Ronnie, but about the passions he has unleashed in his household–between his parents, and between his sister and her suitors, declared and undeclared.

A story like this, when done badly, is about plot. When done well, it is about character. All of the characters are well-bred, and brought up in a time when reticence was valued above all. Today’s audiences have been raised in a climate of emotional promiscuity; confession and self-humiliation are leaking from the daytime talk shows into our personal styles. But there’s no fun and no class in simply blurting out everything one feels. Mamet’s characters are interesting precisely because of the reserve and detachment they bring to passion. Sixty seconds of wondering if someone is about to kiss you is more entertaining than 60 minutes of kissing. By understanding that, Mamet is able to deliver a G-rated film that is largely about adult sexuality.

That brings us to the key performances by Northam and Pidgeon, as Sir Robert and the suffragette. Pidgeon’s performance has been criticized in some circles (no doubt the fact that she is Mrs. Mamet was a warning flag). She is said to be too reticent, too mannered, too cold. Those adjectives describe her performance, but miss the point. What her critics seem to desire is a willingness to roll over and play friendly puppy to Sir Robert. But Pidgeon’s character Catherine is not a people-pleaser; she is scarcely interested in knowing you unless you are clever enough to clear the hurdle of her defenses. Her public personality is a performance game, and Sir Robert knows it–because his is, too. That’s why their conversations are so erotic. Spill the beans, and the conversation is history. Speak in code, with wit and challenge, and the process of decryption is like foreplay.