The voices are hushed, like the quiet flow of a steady stream through the Kentucky woods. The palette is muted, with taupes and oatmeals and heather grays, like the pages of a Jenni Kayne catalogue come to life.

Everything about “The History of Sound” is restrained to a fault—until it’s about the music. And then it bursts with passion and pure emotion. The folk songs that provide the film’s spine spring from a deeply authentic place, infused with a love of storytelling and a yearning for connection with the past.

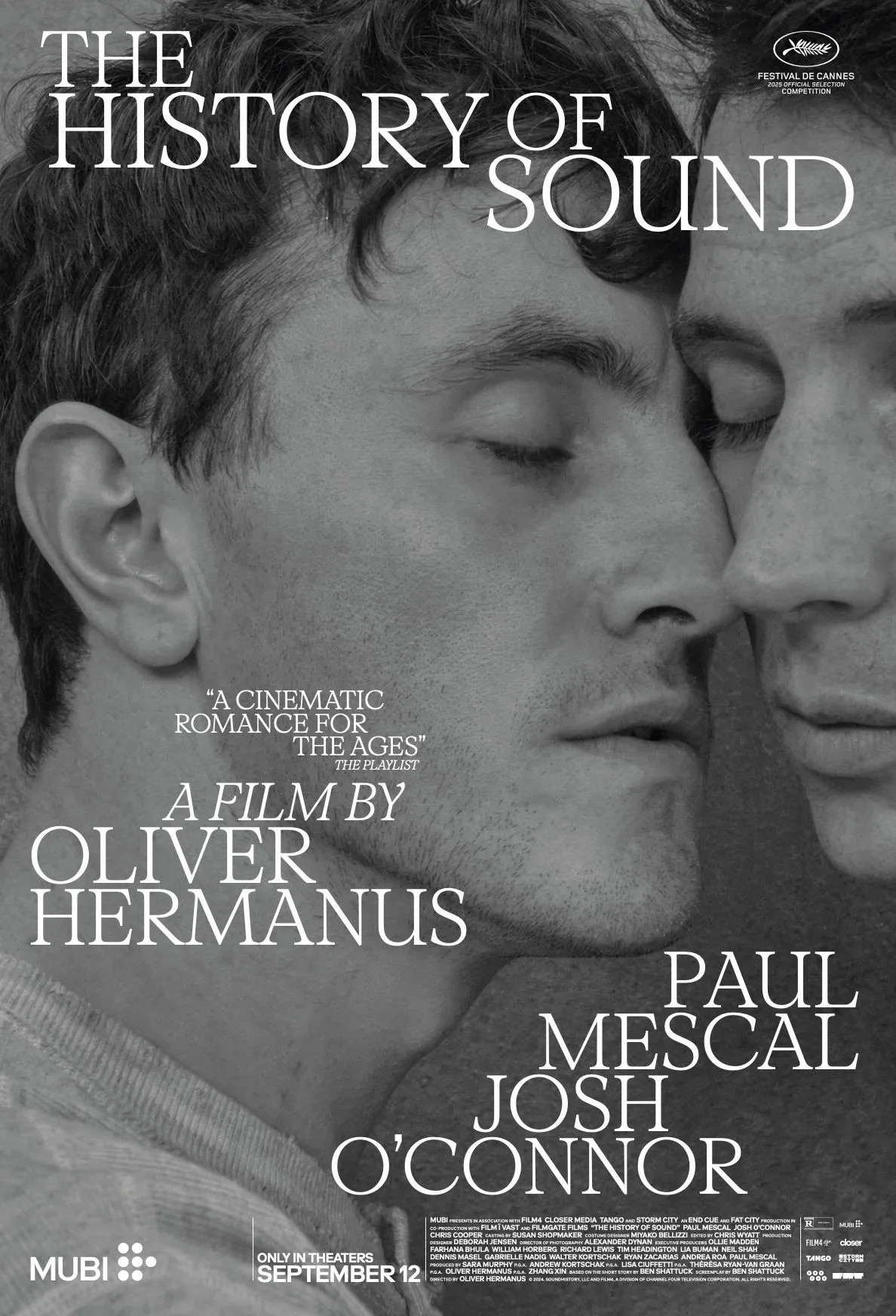

Director Oliver Hermanus’ drama is about the romance that forms between two men who find each other through their shared love of those timeless tunes. Because of the period when the story takes place, World War I, theirs is a love that cannot be. But we barely feel the anguish of that harsh truth, and when we do, it’s too late.

Still, Paul Mescal and Josh O’Connor have a sweet, easy chemistry with each other. Simply sharing their company as they share company provides its own pleasure.

In adapting his short story of the same name, Ben Shattuck traces the love affair between these two men who couldn’t be more different outside their mutual obsession with music. His story begins in 1910 Kentucky, where, in an opening voiceover (the wise, gravelly tones of Chris Cooper), we learn that young Lionel is a musical prodigy. He has perfect pitch; his mother sneezes, and he can name that note. His ability lifts him out of rural poverty and carries him to the elite Boston Conservatory to study vocal performance.

Now the year is 1917, and Mescal is playing Lionel. But despite his compelling naturalism, he’s also distractingly too old for the part. When we first see Lionel as a shy child on his family’s farm, he’s about 10. That would make him about 17 by the time he gets to Boston. Mescal is nearly 30 and looks it. I kept doing the math in my head to make it make sense, and couldn’t shake it.

Anyway, Lionel and O’Connor’s David meet cute at a bar, where David is playing the piano and singing a folk song Lionel recognizes from his youth. Through the dimly lit crowd of drinkers and the haze of cigarette smoke, their connection is unmistakable. David is charismatic and tragic; wealthy and sophisticated, he grew up an orphan in Newport, Rhode Island. (“I was momentarily unparented,” he playfully explains in one of the film’s few amusing lines.) Their first tender night together is clearly life-changing. There’s no: Is-he-or-isn’t-he? They just know. It just is.

After a brief separation when David goes off to fight in the war—“Don’t die,” Lionel orders as he leaves—they eventually reunite to travel throughout rural Maine, knocking on doors and recording the folk songs that families have passed down from one generation to the next. This section is the heart of the film and gives it real spark. The desaturated visuals from cinematographer Alexander Dynan (“First Reformed”) soften these intimate moments, but the power behind the vocal performances is undeniable. From front porches and kitchen tables, the ability of music to transform and transcend is evident.

If only the romance at the film’s center were so engaging. Mescal and O’Connor have a lovely way with each other, harmonizing between the trees or lazing by the river at golden hour. But Lionel is far too passive. He’s literally along for the ride. Maybe he feels inferior because he doesn’t come from means like his peers at the conservatory do, and that’s why he’s so reserved. Maybe because of the era when “The History of Sound” takes place, he can’t be demonstrative in his affections. However, when he’s away from David, he becomes far less interesting. We miss David, too, when he goes away during the latter part of the film. O’Connor is one of the most exciting actors working today, and we feel his absence.

To say much more would enter spoiler territory, but the film takes a few more time leaps forward to reveal the life in music that Lionel forges on his own. But no matter how accomplished he becomes, he remains frustratingly enigmatic. A stop in Rome does allow for gorgeous splashes of color and sunshine, though, along with some scenic locales.

Hermanus’ previous film, “Living”—a remake of the Kurosawa classic “Ikiru,” set in London—also featured a stoic figure at its center. But Bill Nighy’s character had the benefit of enjoying a breakthrough, a satisfying emotional arc. Here, the film’s coda merely provides a brief moment of heartbreak (and an inspired contemporary music choice), along with the lingering, wistful melody of what might have been.