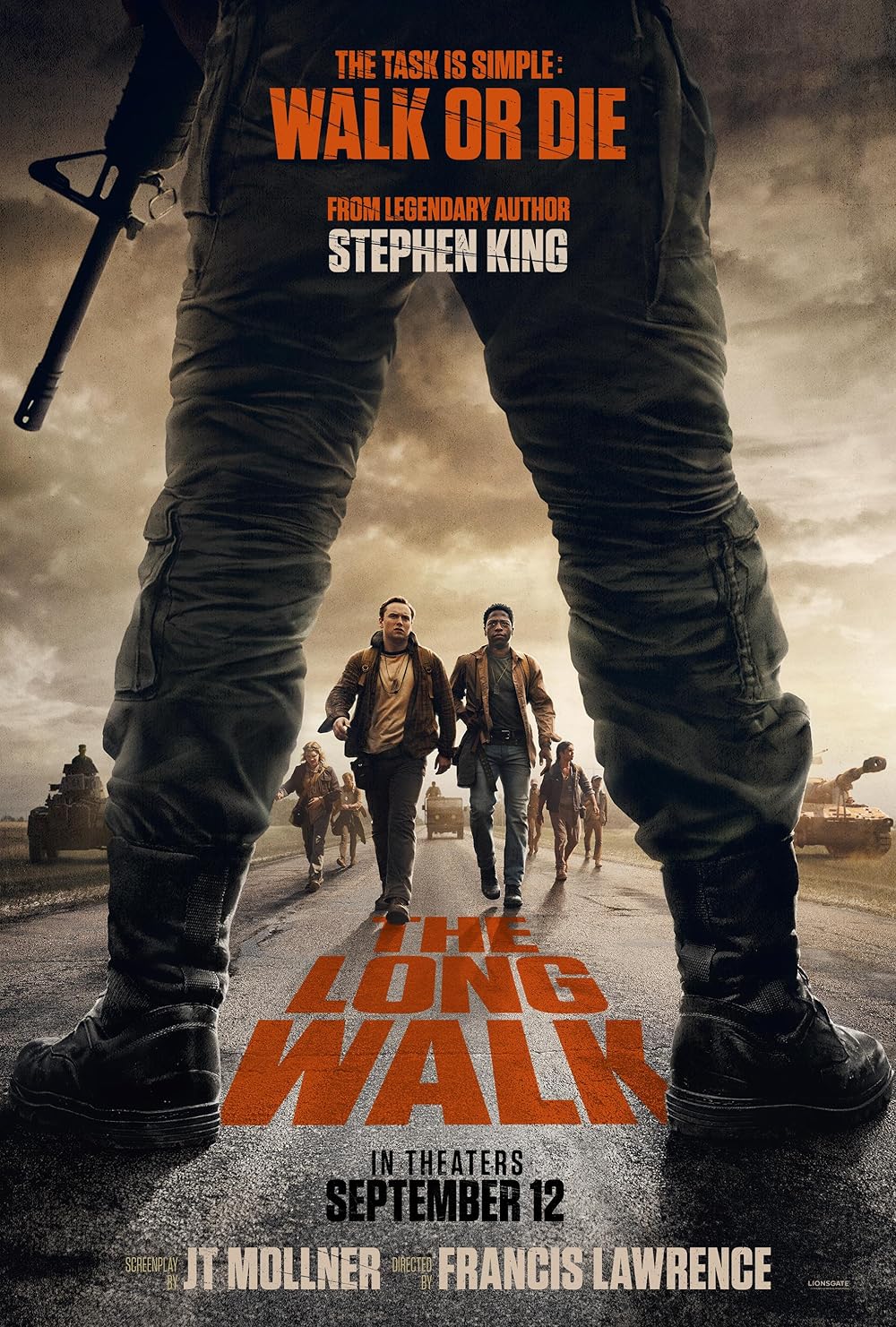

Long before he became the master of horror, Stephen King wrote dystopian novels in the late 1970s and early 1980s under the pseudonym Richard Bachman. These were bleak, dark works that imagined worlds in which economic and social collapse would lead to authoritarian regimes that offered violent, bloody spectacle to pacify and motivate their terrified, marginalized populace—blood and circuses. It’s fitting that this year, we’ll get two of them: another adaptation of “The Running Man” by Edgar Wright, and this one, “The Long Walk,” courtesy of Francis Lawrence. Between these two cardio-heavy pictures, I hope none of us skipped leg day.

The concept, in classic King fashion, is simple but alluring, and designed to explore the kind of adolescent male bonding the author honed in works like Stand by Me and IT. In a desolate alternate history of the 1970s, a postwar America sets an annual contest for fifty kids, each representing their home state; their goal is to walk, slowly but steadily, never dropping below 3 miles per hour, down a long country highway. If they lose speed, they get a warning and ten seconds to regain their footing. Three warnings, and the garrison of soldiers following them with M16s shoots them dead.

The methodical premise feels difficult to dramatize, and it’s to the credit of director Lawrence (who, after four “Hunger Games” films, knows a thing or two about teens trapped in dystopian games for public consumption) and his game cast that “The Long Walk” maintains its pace as long as it does. Amid the dozens of contestants, we’re left mostly to focus on a few core kids, like wisecracker Olson (“Karate Kid: Legends” standout Ben Wang) and antagonistic wild card Barkovitch (Charlie Plummer). But the book, and JT Mollner’s screenplay, focuses most acutely on the budding friendship between sensitive Ray Garraty (Cooper Hoffman) and the punchy, endlessly optimistic McVries (the endlessly magnetic David Jonsson). In a game where it’s every man for himself, the two of them figure out ways to help each other, and occasionally their fellow contestants, stay alive just a little bit longer.

As we float along with the contestants, while they fight sleep, exhaustion, and the elements, “The Long Walk” becomes less about the destination than the journey; cinematographer Jo Williams ushers the kids along a seemingly endless road, keeping them in a kind of spiritual purgatory as Mark Hamill‘s Mayor barks at them (in a performance so cartoonish as to be somewhat miscalibrated to the grimy sentiment of the picture; it’s the rare casting misstep found here). The kids occasionally walk along Dust Bowl-esque tableaus of twisted Americana, like a lone sad woman standing in front of a church, or empty storefronts along the main thoroughfare of an abandoned town. There’s something very “Grapes of Wrath” about the version of the country they trudge through, visions of a country so impoverished that they’ll search for meaning in anything, even state-sponsored murder.

But for as ironically static as JT Mollner’s script is, the conversations and dynamics become innately cinematic. It helps, of course, that the film has such a staggering cast to work with; Hoffman and Jonsson make for such an invigorating pair, kids who maintain their moral center in an environment where kids would more likely behave like Barkovitch (taunting and sabotaging his fellow competitors so they fail and die), and building a small community of survivors around them whom they can lean on in times of exhaustion. Their backstories are thin, and revealed only through vague glimpses of dialogue (or what little we get of Judy Greer as Garraty’s worried mother). Still, the strength of the performances gives those gaps a mystique that wallpapers over their perceived thinness.

Then, of course, there’s the tension of the contest itself, which carries its own devastating scares. This isn’t a horror movie in the traditional sense; the terror comes from the growing, ratcheted-up exhaustion each of our characters feels, as each new stumble or logistical hurdle puts them on an instant clock for death. The deaths themselves are brutal to the point of splattercore—skulls burst open with the force of bullets, legs are pulverized by tank treads—which punctuates how psychologically damaging it must be for the kids. Lawrence delights in showing us what it must feel like to force yourself to keep walking after your ankle is broken, or to get a bullet in the brainpan because you can’t stop shitting yourself fast enough to take another step. Children cry out for their mothers, or beg for mercy, or worse, defiantly try to go out on their own terms. (It’s no coincidence that King wrote this not long after Vietnam; this is a work about the terror of the draft, where young men are sent off to die at the behest of military orders, while an aghast American public watches on their TVs.)

Sometimes, the double-edged sword of the script’s focus on Garraty and McVries means that late-game sacrifices don’t hold much weight. We didn’t really get to hear much from this or that kid anyway, despite walking so many miles with them, after all. But the spectacle of inevitable violence remains haunting regardless, especially as we watch these kids, resigned to their fate, try to go out with as much of their humanity intact as possible. For some, that means revenge; for others, it means sending a message. For Garraty and DeVries, it means building a bond that will carry them as far as their legs can take them. Turns out the real long walk was the friends we made along the way.