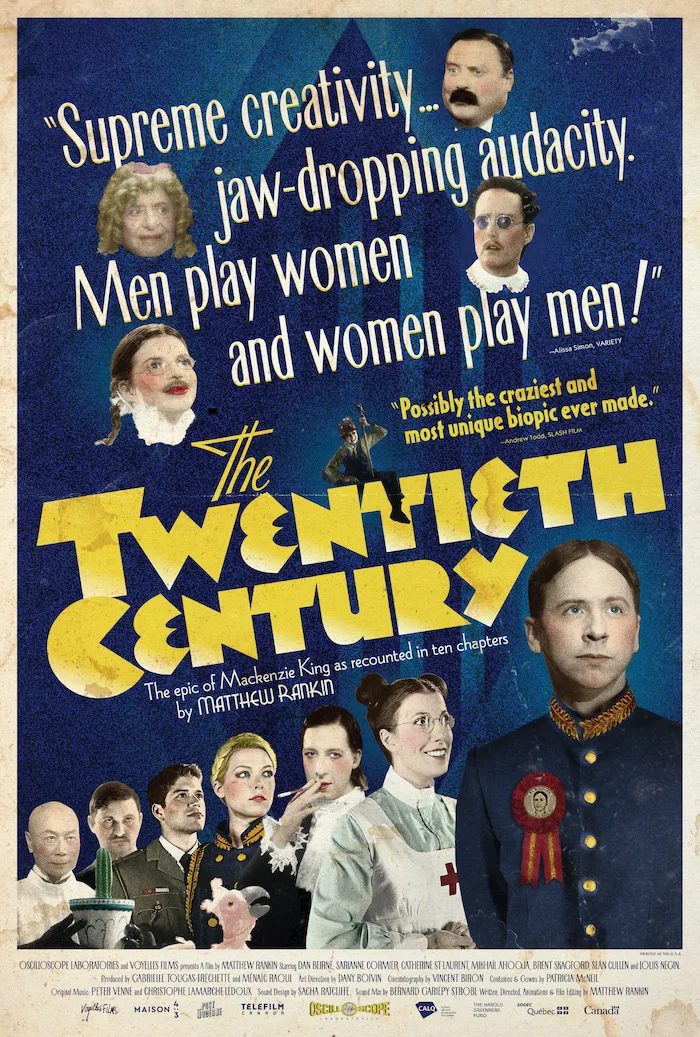

One of the few silver linings amidst this year of lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been the opportunity for extensive self-reflection. The historical myths so often taken for granted in American classrooms have been upended, while our own capacity for change had been tested like never before. Perhaps no country has produced satires more fitting for this interminable period than Canada, which broke records at this year’s Emmys with the sixth and final season of its soul-cleansing sitcom, “Schitt’s Creek,” featuring career-best work from Catherine O’Hara and Eugene Levy. Serving as a 21st century spin on fellow SCTV alum Harold Ramis’ classic film, “Groundhog Day,” the show centers on privileged family members who are forced to live together in a cheap motel once they’ve lost their fortune. Only after enduring a purgatorial series of humiliations do these characters begin evolving into better people, and their newfound humanity is portrayed with disarming sincerity. Of course, redemption is easier for individuals to achieve than an entire nation, and in Matthew Rankin’s captivatingly surreal debut feature, “The Twentieth Century,” the less admirable and frequently glossed-over aspects of Canadian identity are lampooned with dazzling ingenuity. Regardless of one’s whereabouts or knowledge of the Great White North, viewers will likely find this comic fable chillingly relatable, as the world teeters on the brink of totalitarian collapse.

Though the film is ostensibly about the early years of William Lyon Mackenzie King that preceded his three non-consecutive terms as Canada’s prime minister, it is less of a biopic than a daydream had by a bored high school student in history class, as his thoughts heedlessly shift toward far more diverting memories of Monty Python. To those unschooled in his legacy, King may seem like an odd choice for ridicule, considering he successfully led his nation through World War II while forming crucial social welfare programs. However, a closer look at his life reveals numerous eccentricities—his lack of social skills, his status as a potentially closeted bachelor, the influence of séances on his political decisions—and more than a few potentially catastrophic blind spots. He failed to take the Great Depression seriously, disliked President Roosevelt’s New Deal, barred Chinese immigrants and Jewish refugees from entering his country and even predicted in the 1930s that Adolf Hitler would one day be considered a hero on the order of Joan of Arc. “He is really one who truly loves his fellow-men, and his country, and would make any sacrifice for their good,” King naively wrote in his journal, assuming he could help guide Hitler, and Germany as a whole, to a place of peace. This staggering level of hubris affirms that the prime minister had his head at least partially lodged in the clouds, which makes this film’s aesthetic drenched in heightened artifice entirely appropriate.

Inspired by the aching vulnerabilities voiced by King in his own diaries, “The Twentieth Century” takes the form of a dizzying portal into the politician’s subconscious, casting real people from his life into roles that are either fictional or composites, just as King himself recast Hitler as Joan of Arc. For example, Lord Minto, an amateur sports enthusiast, is transformed here into Lord Muto (Séan Cullen, channeling Jim Broadbent in “Moulin Rouge!”), a monstrous dictator spewing hateful lies about the Boer people of South Africa whom he hopes to exterminate, claiming they are half-man, half-elephant. Rankin has particular fun with Dr. Wakefield (Kee Chan), a sinister character that the director admitted at the film’s TIFF premiere was inspired by John Harvey Kellogg’s alleged plan for his popular cornflakes cereal to prevent its consumers from masturbating. King’s sexual shame and repression, which may have been fueled by the feelings he supposedly harbored for his appointed Governor General, Lord Tweedsmuir, are manifested in a foot fetish that threatens to become “a crime against national dignity.” Wakefield places an alarm on King’s genitals that will sound whenever he’s aroused, resulting in one of many uproarious set pieces. As portrayed by the sublimely funny Dan Beirne, King comes off as a petulant momma’s boy who is so thoroughly clueless, he continuously mistakes a harp for a trumpet. His idea of cheering up an ailing girl (Satine Scarlett Montaz) at the Institute for Defective Children is to gift her a mass-produced badge displaying his face, while handing her a flimsy handkerchief when she coughs up blood.

Every frame of this picture is an absurdist marvel, with its expressionist sets, ill-fated puppets and ejaculating cactuses. Not only does the film’s compressed aspect ratio and old-fashioned visuals warrant comparison to the work of fellow Canadian visionary Guy Maddin, Rankin also nails the celebrated filmmaker’s distinctive brew of humor, irony and nagging melancholia. In true Pythonesque form, various actors are cast against gender, including frequent Maddin collaborator Louis Negin as King’s mother, whose derisive cackle would fit snugly into Room 237 at the Overlook Hotel. Dany Boivin’s art direction makes striking use of a triangular motif, seen in everything from romantic ice flows to desolate hills peppered with tree stumps. Whether this imagery is meant to represent the “North Atlantic triangle,” which notes the dependency of Canada on strong relations with the U.K. and U.S. (and may have spurred the country’s support of British oppression during the Second Boer War) is left up to one’s interpretation. Of course, such a scholarly approach to describing this picture fails to convey just how funny it is throughout, especially when the characters’ antics are at their most ridiculous. One of the film’s funniest sequences finds the candidates for prime minister being tested on leadership skills such as ribbon-cutting, butter-churning, endurance tickling and waiting your turn (King is praised for exuding the valued Canadian trait of passive-aggression).

Like the ensemble of “Schitt’s Creek,” King does eventually flirt with making noble life decisions that aren’t determined by the creaking wheel of destiny. As he becomes disillusioned by the corruption in his society, he considers running away with the infatuated French Nurse Lapointe (Sarianne Cormier), who fuses together the real-life identities of King’s long-time lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe, and a nurse whom he became briefly entangled with (“We could conjugate French verbs together!” he sighs). Yet it is King’s passive obedience and tendency to settle for middle-of-the-road mediocrity that Rankin’s anti-establishment farce aims to skewer most of all, and by the time it arrived at its deliberately disquieting conclusion, I found myself too unsettled to crack a smile. It’s impossible not to think of certain modern-day fear-mongering tyrants when Lord Muto observes, “Give the people hope and there will be endless disappointment, but fill them with nightmares, and they will follow you straight into hell.” Sometimes the most useful thing a satire can do is deliver laughs that are so scathing, they become lodged in your throat and may take a while to digest. At a time when normalcy has routinely backflipped into a pool of insanity, “The Twentieth Century” makes perfectly perverse sense.

Now playing in virtual cinemas.