Mark Cousins is equally known for film writing and filmmaking. The two overlap to such an extent that by if you tried to draw a Venn diagram showing the relationship between them, it would just be a circle. A critic, scholar, programmer and documentarian, Cousins is best known for “The Story of Film: An Odyssey” and its variants, including “A Story of Children and Film” and “The Story of Film: The New Generation” as well as for more, shall we say, idiosyncratic works. “The Eyes of Orson Welles” is framed as a letter to the director, who died in 1985, while “What is this Film Called Love?” is a walking tour of Mexico City with Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein (1898-1948) as imaginary travel companion, and “Bigger than the Shining,” a film about copyright and the question of whether two people can ever really see the “same” film, was only shown once and then intentionally destroyed. Cousins works so intuitively and personally, often generating whole projects off a sudden insight or inspiration (“A Story of Children and Film” was sparked by looking at home video footage of his niece and nephew) that the results are necessarily going to be hit and miss.

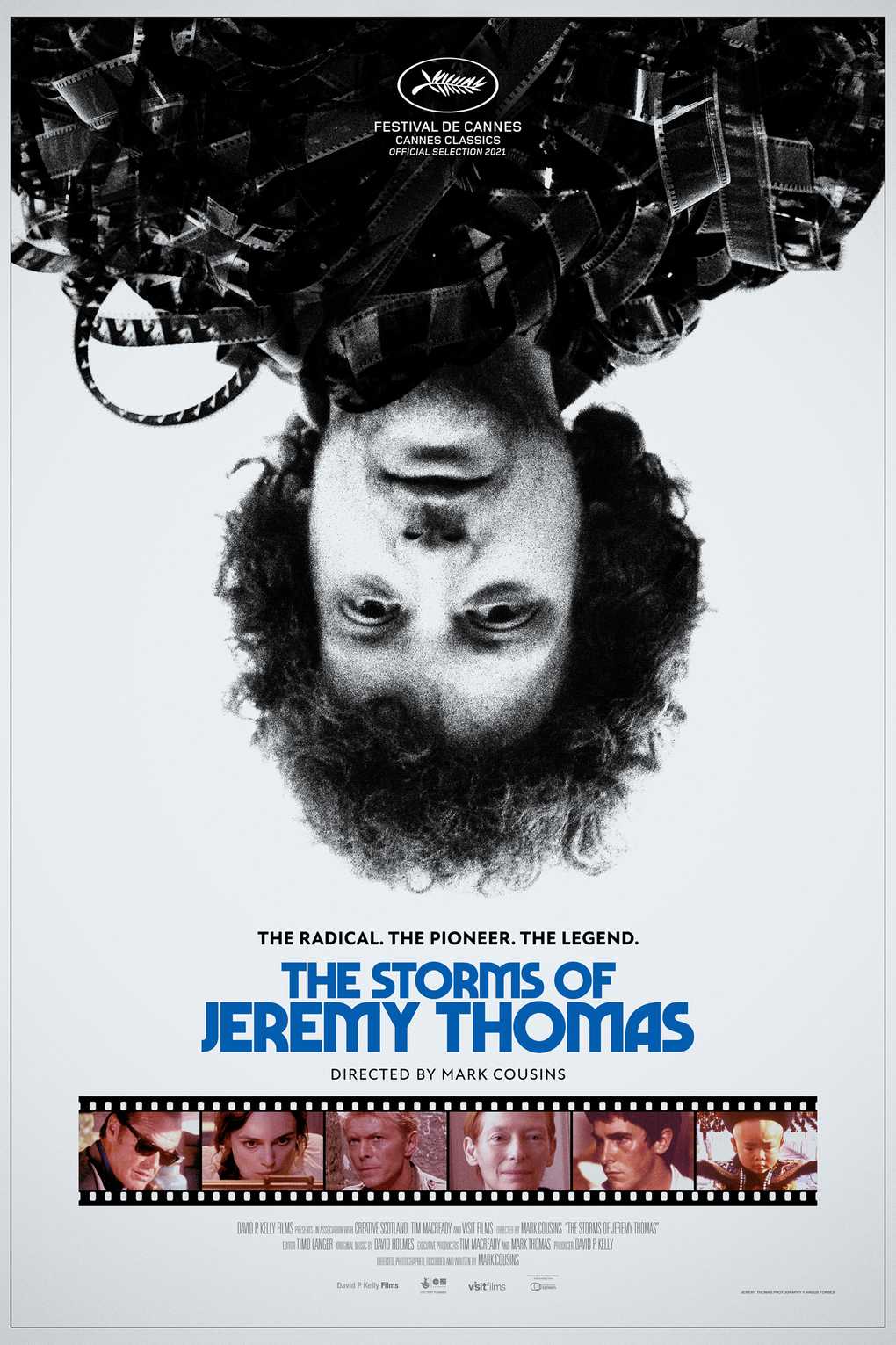

“The Storms of Jeremy Thomas,” about the career of one of the most important film producers of the last 50 years, is one of Cousins’ best and most entrancing films. It’s a “road movie” that follows Thomas, the producer of “The Last Emperor,” “Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence,” “Sexy Beast,” “Crash,” “The Naked Lunch,” and other notable features, as they drive from the UK to the Cannes Film Festival, with both Thomas and his biographer ruminating on what the work means and where it came from. As is usually the case with Cousins, it’s impossible to coldly analyze why this movie feels so on-point while others might seem half-baked, and there will surely be reviews contrary to the one you’re reading.

This one has a different feel from a lot of the others, partly because even though the films Cousins name-checks are well-known or semi-known (at least to the sort of person inclined to seek this documentary out), in terms of his human subject he’s got a blank canvas to paint on. Thomas is a friend of Cousins and has a long and impressive resume, but his name is largely unknown to the moviegoing public. (When he accepted the Best Picture Oscar for producing Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Last Emperor,” most viewers didn’t know his name until the broadcast booth flashed it onscreen.) The freshness of the subject lets Cousins paint an audiovisual portrait of Thomas (and himself; there’s always a lot of Cousins in every Cousins film) using the intellectual/aesthetic divining rod techniques he’s been developing for decades while neutralizing nitpicks about why he spent so much time on this part of the subject’s life and not enough on that, and whether the overall approach suits the subject.

“The Storms of Jeremy Thomas” arrives in time for the 50th anniversary of the Recorded Picture Organization, which Thomas founded in 1974. A scion of a film industry family (he’d be called a “nepo baby” if he came up today), he’s described by Rebecca O'Brien, a producer for Ken Loach and Lynne Ramsay, as “a producer’s producer. His history with amazing European filmmakers and beyond is just incomparable.” He made multiple films with Bertolucci (including “The Sheltering Sky” and “The Dreamers“) as well as Nicolas Roeg (“Bad Timing: A Sensual Obsession,” “Eureka,” “Insignificance“) and David Cronenberg (one of the liveliest sections has Thomas recalling the premiere of the latter’s “Crash,” which prompted the Daily Mail headline “a movie beyond the bounds of depravity”).

Thomas, now 74, is a compelling camera subject even when silent, and more so when speaking. He drives like “a teenager,” per Cousins’ narration; survived cancer, and evolved due to his brush with death; worships the bohemian or liberated sensibilities of European artists, and has the rumbling baritone voice of an old French character actor.

It seems as if most of Thomas’ interviews with Cousins were recorded separately from the shoot itself and then treated as voice-over narration to accompany the footage Cousins shot of the Cannes trip and the clips he selected to accompany the career analysis. The separation of narration and image seems awkward initially but ultimately proves a masterstroke. It makes the movie play like a deathbed “exit interview” by somebody who’s still very much alive, evoking the sort of quasi-European art cinema movie that would’ve sparked young Jeremy Thomas’ imagination before he decided to get into the producing business and make his own equivalents.

Cousins’ narration compares Thomas to Virginia Wolff in a list of artists who possess “quiet radicalism,” along with painters Francis Bacon and J.M.W. Turner and filmmaker Michael Powell. It’s a reach within the film’s grasp. The intertwining of Thomas’ and Cousins’ voice-overs subtly connects the film to that formative period in English language fiction in the late 19th and early 20th century when Wolff and other writers were innovating in hopes of approximating the complexity of personality and consciousness. And it helps the audience navigate the disparate sections of the movie, which go wherever the crests and troughs of Thomas and Cousins’ interactions take them.

Buffs interested in discovering what Thomas thought of boldfaced names he’s worked with won’t find much in the way of salacious gossip or shocking revelations. But the tidbits are fun and enlightening. Debra Winger (of “The Sheltering Sky”) and Tilda Swinton (with whom Thomas has collaborated on numerous projects related to filmmaking and film exhibitions) sit for interviews with Cousins about Thomas and praise his energy, openness, and resourcefulness. It’s a mutual admiration society: Thomas describes them as kindred spirits whose instincts help unify and clarify a movie’s themes and intent. Thomas also talks about “Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence” costar David Bowie (mainly concerning celebrity); Marlon Brando, who gave one of his last film performances in the little-seen Thomas-produced Johnny Depp film “The Brave” (Thomas calls him “one of the best”), and Tony Curtis, who explained his tendency to caress cameras placed near him for closeups by explaining: “Mr. Thomas, it loves me, baby.”

Cousins’ narration gets a bit MFA fiction workshop at certain points, but that’s a feature of his work, not a bug (in another life, he might’ve been a novelist, possibly in a Beat writer mode). The film is organized around storms and divided into numbered chapters with titles like “Sex” and “Death.” It gets a bit fanboyish when delving into the sexual and political content of Thomas’ projects. Cousins accounts for this by noting that his own tastes were partly formed by watching Thomas’ movies.

Regardless, there’s a place in current documentary cinema for a lament about how the relentless corporatization of mainstream films helped feed a squirmy Puritanism that eschews psychological complexity as well as adult sexuality and insists that bad behavior be labeled as such. “The Storms of Jeremy Thomas” encourages viewers to broaden their horizons and seek out unknown and possibly uncomfortable work. It portrays the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s as a lost continent of handsomely funded movies aimed at sophisticated and curious adults rather than The Kid Inside All of Us. The voyeuristic impulse that has always fueled cinema to some degree is acknowledged in several film clips, such as the brother in “The Dreamers” watching his sister and the visiting American getting intimate, and the title character in the Thomas-produced “Dom Hemingway” proclaiming that a painting of his johnson “should hang in the Louvre.”

Cinema, Swinton says in an interview with Cousins, “asks for something visceral. And that’s the best cinema: the cinema that asks for that.” Cousins praises Thomas for helping important filmmakers push right up to the edge of whatever lines were being drawn at the time, then go over because that’s what art is empowered to do. Cousins joins the movement himself by pairing a rumination about Thomas’ libertine sympathies (“is the producer, the prince, a petrol head, a bohemian?”) with a video selfie taken while he’s wading naked in the pool of the house Thomas rented at Cannes (full-frontal, but partly obscured by water).

“I like the counterculture,” Thomas says at one point, summing everything up. “I’m not seeking the popular culture. I enjoy a Spielberg movie like everybody else. But they’re not what I’m looking for. The most famous paintings are available to all, out in the first hall in the museum. The counterculture is something you sort of…you have to look for it. You have to find it.”

Now playing in theaters.