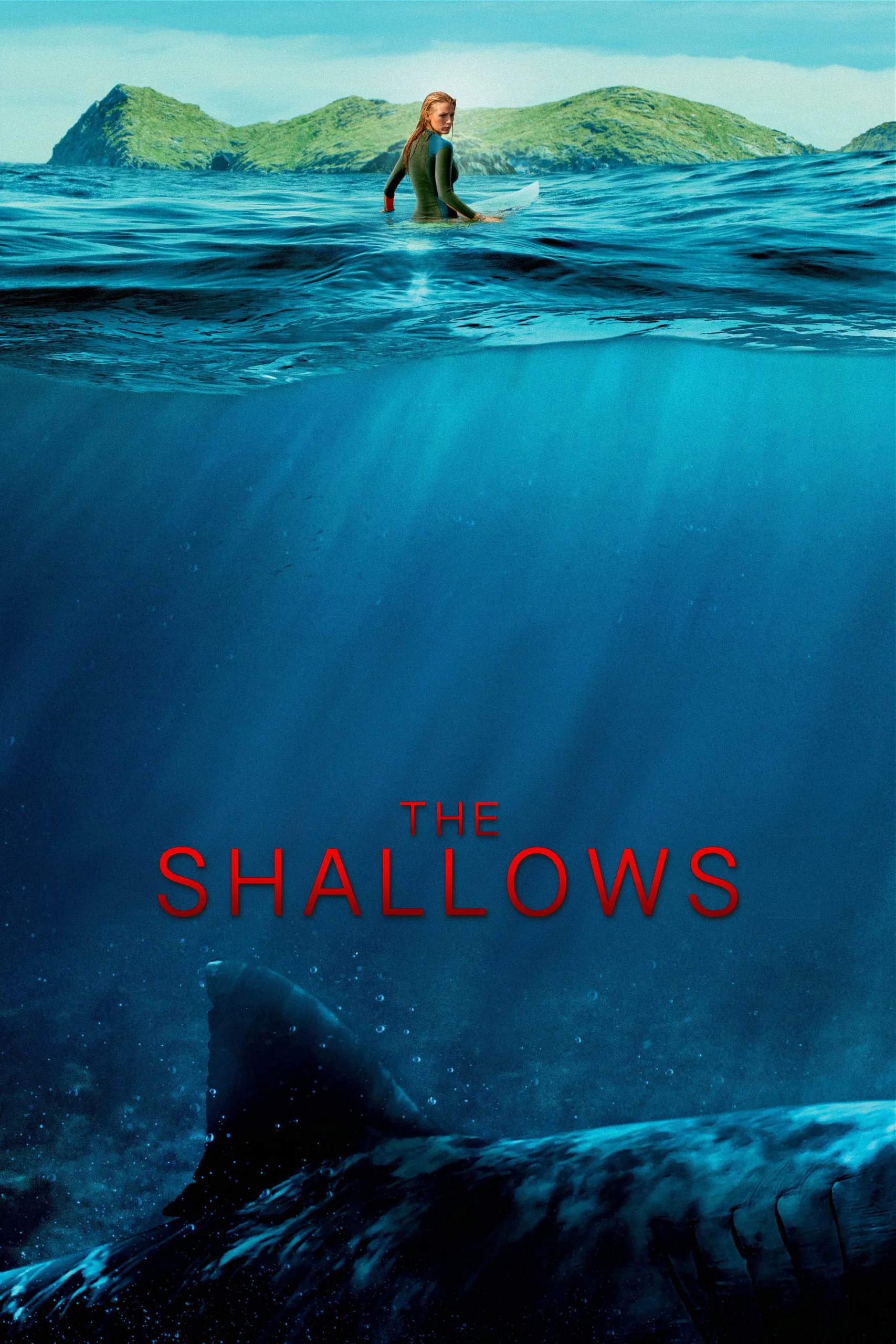

“The Shallows” is an 87-minute thriller set mostly in a lagoon where an injured surfer is battling a shark. There’s not much plot beyond that, and what little the movie tries to add doesn’t make it richer. Its situations are primal and often terrifying; that they unfold in a contained space—a stretch of shore-bordered water that looks to be about a kilometer across—intensifies the suspense. At its best, the film from screenwriter Anthony Jaswinski and director Jaume Collet-Serra (“Non-Stop,” “Run All Night“) is as close to a pure action film that mainstream cinema has seen since “Mad Max: Fury Road.” It often uses its star, Blake Lively, the way “Fury Road” director George Miller used his actors: as a kinetic sculptural object.

“The Shallows” is a survival thriller: woman versus nature, with nature represented most but not all of the time by a shark the size of a Winnebago. I’m exaggerating only a little: this slate-grey beast is as immense as the great white that took down the Orca in the first “Jaws,” and it’s a lot more agile, leaping into the air like a porpoise and twisting to snatch prey in hard-to-reach places.

Lively’s character, a medical school dropout named Nancy, encounters the shark while visiting a beach in Mexico that used to be a favorite of her mother, who recently died of cancer. There’s backstory conveyed through iPhone photos and expository dialogue, and it’s as necessary to our appreciation of Nancy’s predicament as Dennis Weaver’s internal monologues were in Steven Spielberg’s breakthrough, pre-“Jaws” TV movie “Duel.” I.e., it’s not. This is a lean, brutal movie about endurance and problem solving. It revolves around questions that are spelled out so clearly by the filmmaking—much of it wordless, driven by images, sound effects and Marco Beltrami’s breathless score—that when Nancy mutters “forty meters” or “I’ve got you figured out,” it’s as if the film has lost faith in its power.

Lively is superb here, giving one of those hyper-focused, action-lead performances that’s as much an athletic feat as an aesthetic one. There are a handful of supporting characters, most of whom end up as shark bait, but in the end, “The Shallows” is a one-woman show that puts Lively on a jagged rocky pedestal and worships her. She wears a bikini so radiantly orange that it seems to refract moonlight during night scenes, and not since the heyday of Kevin Costner in the ’90s has a star’s posterior been so lovingly scrutinized. Lively does a lot of her own surfing (with a double filling in during the most dangerous bits). She runs and climbs, screams, cries, curses, dives into murky depths, swims through chop. Like Tom Hanks in “Cast Away,” she has a non-human “buddy” to talk to: a seagull that she names Steven (get it?). It’s corny—a lot of the film is corny, often knowingly so—but damned if you don’t find yourself loving that bird and worrying that it won’t last through the end credits.

After a while you get to know Nancy’s physical condition so well that you could fill out her hospital admission forms, and you become so familiar with the beach that you could draw a map noting major points of interest: the shoreline, a buoy, two outcroppings of rock, a rotting whale carcass floating farther out. The shark’s not the only threat: the ocean is filled with plants and animals that have no opinion on whether the star survives. The filmmaker keeps us close to Nancy whenever possible—sometimes we’re literally in her face—and it takes a page from Spielberg and reveals the shark in pieces: a dorsal fin here, a flash-cut to jagged teeth there, a shadow gliding between the camera and Nancy’s kicking legs.

“The Shallows” suffers from an inability to realize how little it needs to get its points across. It might’ve been truly powerful, as opposed to clever, without the exposition and inspirational back-story—like a woman-centric answer to the Robert Redford survival picture “All is Lost,” which treated an old man’s boating mishap as if it were a deleted chapter of “The Odyssey.” There’s a moment near the end that would’ve made a perfect final shot—you’ll know it the instant you see it—but the movie feels compelled to keep going, to its detriment. And there are times where the special effects and editing aren’t as sharp as Lively’s performance deserves.

But it’s still a taut, brutal film, pitting a ravenous sea creature against a woman as hard as coral. It wears you out.