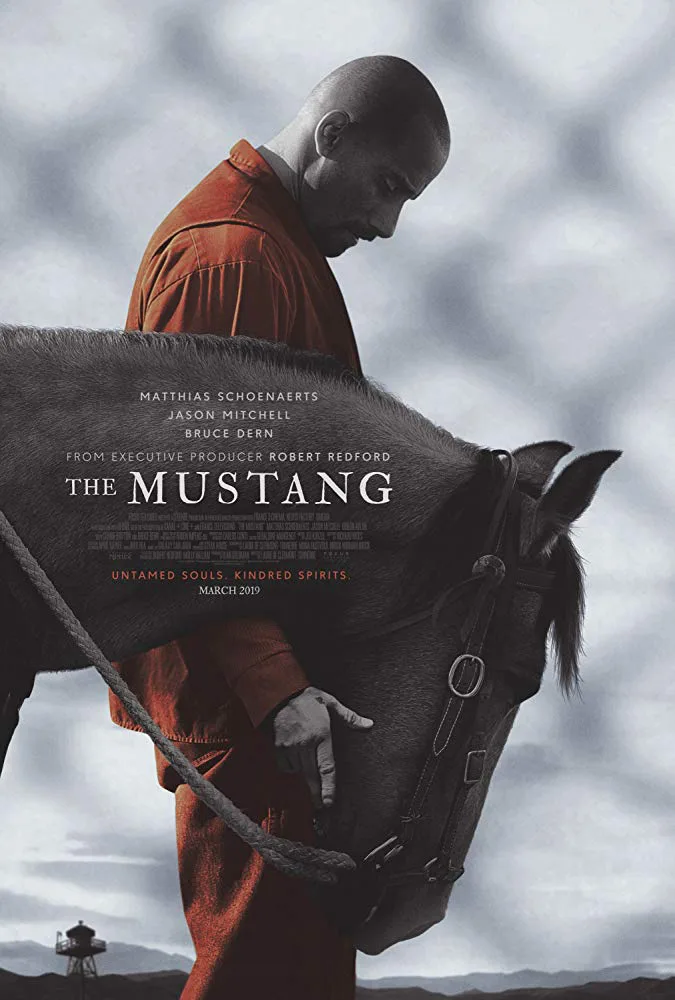

A man of few words in a rural Nevada prison, convict Roman Coleman is unable to keep his temper in check in Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre’s sober and humanistic character study “The Mustang.” It is that severe lack of anger management that got Roman incarcerated over a decade ago, with half of his sentence for a tragic case of domestic violence still remaining. In fact Roman, stupendously portrayed by Belgian actor Matthias Schoenaerts (“Far from the Madding Crowd”) in a quiet, expressive performance, doesn’t hesitate to declare that he isn’t good with people after years of confinement. He gets rehabilitation help from a prison therapist (Connie Britton) from time to time, and yet he remains a steadfast picture of tortured masculinity: broken, remorseful and even angrier because of the helplessness his solitude forges. If “The Mustang” was a through-and-through Western—and Clermont-Tonnerre’s film carries graceful, gentle traces of the genre throughout—Roman would still be an outlaw capable committing a crime in the blink of an eye. But in prison, his ticking bomb of a rage finds alternate targets and bursts out of his fists when he loses control of his emotions. Indeed, he isn’t good with people and they can’t help him in return.

In the grand tradition of horse movies, an untamed, especially wild stallion crosses paths with Roman when he is required to participate in the prison’s “outdoor maintenance” program. But this film is neither “Seabiscuit” nor “The Horse Whisperer”— Clermont-Tonnerre finds her inspiration and source material in present day, in more austere and forgotten corners of the country. Through the opening credits, we learn that there are approximately 100,000 mustangs in the wild across 10 American states and the government can support less than a third of them only. The rest are sometimes adopted, sometimes kept from sight in various long-term facilities or given to prison inmates to train and then sell at auctions through rehabilitation programs. It is one such optimistic initiative that Roman gets recruited for. Run by Myles, a veteran, hard-bitten trainer-in-charge (played by a paternal and no-nonsense Bruce Dern, who slips into the role perhaps a little too predictably), the program pairs Roman with the wildest of horses. But will they be able to break and tame one another?

As obvious as the answer to that question might be, Clermont-Tonnerre (along with her co-writers Mona Fastvold, Brock Norman Brock and collaborator Benjamin Charbit) feeds the duo’s steadily building trust and friendship into the story through patient increments. (Sensitive viewers, beware: there is one instance of unexpected and non-fatal animal cruelty that might shake you.) While Roman learns to mold and channel his energy towards a creature just as psychologically misplaced as he, he builds a kinship with the program regular Henry (Jason Mitchell, in a role that begs for more screen time) and continues to accept visits from his pregnant daughter Martha (Gideon Adlon of “Blockers”). The crowded group of co-writers does right by this storyline, introducing Martha’s past and relationship to her dad in a series of steadily maturing scenes, where both Schoenaerts and Adlon deliver some of the film’s strongest moments. Meanwhile, the film never loses sight of the similarities between Roman and his beloved horse he proudly trains for the program’s final auction.

A distracting drug smuggling plotline aside—a diversion from an otherwise intimate and focused film—“The Mustang” becomes an emotional powerhouse in its final act, complete with the National Anthem and an unforgettable, heartbreaker of a parting note. Just as Andrew Haigh did with his “Lean on Pete,” Clermont-Tonnerre brings an outsider’s curious and respectful eye into a marginalized part of Americana on the fringes, mining dashes of hope and kindness in unlikely scenarios. With her cinematographer Ruben Impens, Clermont-Tonnerre captures the vastness of the grounds in the dusty, sun-dappled convention of Westerns. A tender film about forgiveness and second chances, “The Mustang” is a testament to the worthy stories yet to be told about the healing, unbreakable bonds between tormented people and the misunderstood animals that come to their rescue.